Francisco del Rosario Sánchez

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez | |

|---|---|

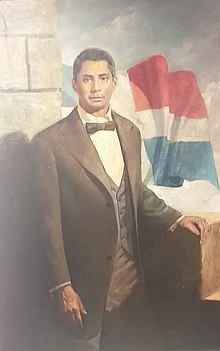

Portrait of General Francisco del Rosario Sánchez c. 1840s–1850s | |

| In office 28 February 1844 – 1 March 1844 | |

| Vice President | Manuel Jimenes (interim) |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Tomás Bobadilla |

| In office 9 June 1844 – 16 July 1844 | |

| Vice President | None |

| Preceded by | Tomás Bobadilla |

| Succeeded by | Pedro Santana |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 March 1817 Santo Domingo, Captaincy General of Santo Domingo |

| Died | 4 July 1861 (aged 44) San Juan de la Maguana, Dominican Republic |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Altar de la Patria |

| Nationality | Dominican |

| Political party | Central Government Board |

| Other political affiliations | La Trinitaria |

| Spouse |

Balbina de Peña Pérez

(m. 1849) |

| Domestic partner(s) | Felícita Martínez, María Evarista Hinojosa, Leoncia Leydes, Mercedes Pembrén |

| Relations | Socorro Sánchez del Rosario (sister) María Trinidad Sánchez (paternal aunt) |

| Children | Mónica, María Gregoria, Leoncia, Petronila, Juan Francisco, Manuel de Jesús |

| Parents |

|

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician, teacher, independence leader |

| Known for | Hoister of the tricolor flag of February 27 Martyr of El Cercado |

| Awards | National hero |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service | 1838–1861 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Dominican War of Independence Cibaeño Revolution |

| Honors | Order of Merit of Duarte, Sánchez and Mella |

| Though not the first constitutional president, Sánchez took office as the first president of the provisional government. The first constitutional president wouldn't be installed until 14 November 1844, with Pedro Santana taking office. | |

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez (9 March 1817 – 4 July 1861) was a Dominican revolutionary, politician, and former president of the Dominican Republic. He is considered by Dominicans as the second prominent leader of the Dominican War of Independence, after Juan Pablo Duarte and before Matías Ramón Mella. Widely acknowledged as one of the Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic, and the only martyr of the three, he is honored as a national hero. In addition, the Order of Merit of Duarte, Sánchez and Mella is named partially in his honor.

Following Duarte's exile, Sánchez took leadership of the independence movement, while continuing to correspond with Duarte through his relatives. Under Sánchez, the Dominicans would successfully overthrow Haitian rule and declare Dominican independence on 27 February 1844. With the success of the separation from Haiti, Sánchez took office as the Dominican Republic's first interim president before ceding his position.

But his ideas of an independent state were fiercely challenged by many within the sector who felt that the new nation's independence was only a temporary success. Because of his patriotic ideals, Sánchez, like many of his peers, would be on the receiving end of these political struggles. His main political rival was none other than the military general, Pedro Santana. His status as a patriot came with many unfortunate consequences, including incarceration, deprived of his assets, exiled throughout the Caribbean, and worst of all, the death of his companions.

By 1861, his worst fears of the end of the republic came to reality upon learning that the pro-annexation group led by Santana agreed to reintegrate Dominican Republic back to colonial status. With no time to waste, Sánchez rushed back to his homeland to challenge this decision, but was lured into a trap by the very same people who allied with him, leading to his unfortunate death on 4 July 1861. His death triggered a national outrage throughout the island, and marking a new era of struggle for independence, which was eventually achieved in 1865.

Background

[edit]Family origins

[edit]Sanchez was born on 9 March 1817, in the city of Santo Domingo, during the years of a 12-year era known to Dominicans as España Boba. This period was plagued into an economic and cultural crisis, in view of the fact that, when Juan Sánchez Ramírez managed to get the "Junta de Bandillo" at the end of 1808 to decide to return to Spain or reincorporate it after defeating French general Jean-Louis Ferrand, in the Battle of Palo Hincado, who applied the Treaty of Basel in 1804, through which Spain ceded the eastern part of the island to France in 1795. Spain was under the Napoleonic invasion, which prevented meeting the requirements of the reacquired colony.[1]

Sánchez was the son of Olaya del Rosario Belén (1791–1849), a free woman of color,[2][note 1], and Narciso Sánchez Ramona (1789–1869), a tall man who was a descendent of slaves.[3][4] (According to a marriage certificate, which lists both of his parents as free people of color, it is presumed that Narciso may have been a freedman). Because of their different racial and social-economical status (hers being superior to his), Narciso Sánchez and Olaya del Rosario married after a special authorisation given by the mayor.

His mother was a hairdresser who produced combs, while his father worked in the meat trade, selling, butchering and raising cattle. Narciso inherited the occupation from his father, Fernando Raimundo Sánchez, (who was part of the free black population) of which mostly took place in the east, an area where livestock production was concentrated. This job placed him in an intermediate situation between the urban and rural world, which was very common at that time. Much of the herd owners preferred to live in the cities, so they appointment administrators. In the cases of Narciso Sánchez, despite being a resident of Santo Domingo, he spent much of his time in the mountainous life of ranching. According to historian Ramón Lugo Lovatón, his professions allowed him to achieve a certain level of social advancement. However, in his will, he clarified that the couple did not bring property to the marriage, indicating that his professions did not bring fortune to the family.[5]

A detail that illustrates the social status of Sánchez's parents is that their initial relationship was concubinage, despite the fact that the mother had Canarian ancestors. Sánchez had an older maternal brother, Andrés, who was adopted by his father. The same hero was born out of wedlock, and although his final last name was Sánchez, he kept his mother's last name as a middle name. (His surnames are inverted because his parents were not married at the time of his birth, marrying in 1819).[6][7] His father had a pro-Spanish position, according to Lugo Lovatón, due to the damage that the Haitians had caused, since 1801, to the livestock activity and its owners, the whites of colonial society, who were his employers. These different political positions between father and son portray the changes in mentality that the young liberal founders of La Trinitaria carried out.[8]

Marriages, children, and descendents

[edit]

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez had children with various women, the first being Felícita Martínez, with whom he fathered Mónica Sánchez Martínez, who was born on January 30, 1838. Some years later, he fathered María Gregoria (Goyita) with María Evarista Hinojosa. who was born on November 28, 1841. Goyita had a daughter named Mercedes Laura Sánchez. In exile, Sánchez fathered with Leoncia Leydes Rodríguez (b. September 15, 1846/47), a daughter whom they named Leoncia Sánchez. This she, in turn, had two daughters: Emilia Mercedes and Manuela Dolores Sánchez. With Mercedes Pembrén Chevalier Sánchez procreated Petronila Sánchez Pembrén, who was born on February 22, 1852, who married León Güilamo, they later procreated Mercedes, Rafaela, Micaela, Alicia, León and Asunción Güilamo Sánchez.

Following the death of his mother Olaya del Rosario, he decided to marry Balbina de Peña, daughter of Luciano de Peña and Petronila Pérez, on April 4, 1849, in front of witnesses Román Bidó, Minister of Justice; Jacinto de la Concha and Pedro Alejandro Pina. From this union Juan Francisco was born (b. April 3, 1852) and Manuel de Jesús, (b. February 16, 1854), who died young. Balbina de Peña died at the age of 70 on April 26, 1895.[9] The only surviving son of the Sánchez Peña household was Juan Francisco (Papi) Sánchez Peña, who held the rank of General, was Minister of Finance of the President Ulises Heureaux and was part of the government cabinet of President Morales Languasco. Juan Francisco Sánchez Peña thus fathered two sons named José and Carlos with Caridad Fernández Soñé, granddaughter of the independentist Francisco Soñé.[10][11][12] Despite Juan Francisco having recognized them, due to family problems related to his mother, neither of them used the surname Sánchez for most of their lives. In the case of Carlos Fernández, it is likely that he adopted it as a second surname later. He later married Eudocia Maggiolo, who produced Francisco del Rosario, Filomena, Fernando Arturo, María, Flérida and Manuel A. Sánchez Maggiolo. Later he married his niece Emilia Mercedes Sánchez, with whom he fathered Manuel Antonio Francisco, María Patria, Manuel Emilio, Héctor, Carlos Augusto, Emilia, Marina Altagracia, and Juan Francisco Sánchez y Sánchez.

Of this generation of grandchildren of the Father of the Nation, there were several who stood out in national life. Carlos Augusto Sánchez y Sánchez was an illustrious jurist, diplomat, historian and literary critic. His brother Juan Francisco (Tongo) Sánchez y Sánchez, a notable Dominican professor, dedicated mainly to the study of philosophy, and a self-taught pianist. With his notes he usually enlivened the clubs and gatherings of which he was a fervent enthusiast.[13] On the side of his grandson José Fernández, he married Juana Roselia Brea Sánchez, a distant descendant of the Spanish conquistador Rodrigo de Bastidas and the chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo. In this way they had as one of their children the writer, doctor and later history professor at the UASD, José Aníbal Sánchez-Fernández (originally born José Aníbal Fernández Brea). He would end up adopting "Sánchez" as his main surname due to a decree issued by Rafael Trujillo which dictated that all the descendants of the patrician change their main surname, if they did not have it, to that of his distinguished ancestor. During the 1980s, he would end up getting involved in a debate with the historian and later president of the Dominican Academy of History, Juan Daniel Balcácer, about the actions of several national figures, including his great-grandfather.[14] José Aníbal in turn was the father of the famous Dominican poet, intellectual, narrator, essayist, professor, columnist and advertiser, Enriquillo Sánchez Mulet.[15]

Education, early years and influences

[edit]

His childhood was spent in the framework of the period of Haitian rule in Santo Domingo, which began in 1821 after the failure of the independence initiative of the enlightened José Núñez de Cáceres, which historians refer to as the "Ephemeral Independence." In spite of his humble origins, Sánchez grew up in a very nationalistic family. He first received his education from his mother, and later by the Peruvian priest Gaspar Hernández, a patriot who encouraged the young Sánchez to follow in his family's footsteps. He was also influenced by his father and aunt, Maria Trinidad Sánchez, both involved in the movement Revolution of Los Alcarrizos, an early resistance that attempted to challenge the dictatorship of Jean-Pierre Boyer, the mulatto General and main architect of the regime. Unfortunately, this conspiracy was eventually discovered by Boyer, who order all those involved to be executed. Narciso, however, was imprisoned. This action not only caused Olaya to suffer, but it also accumulated into a long lasting fear and worry for her children and husband, who by now was marked as an enemy by the Haitians. And as the young Sánchez grew up emulating his father's revolutionary footsteps, her bitterness and concerns would transcend into the future.

In his youth, Sánchez used to accompany his father in the work of managing agricultural properties, which allowed him to interact with people of different social classes. Beyond what was instilled by his family, Sánchez maintained a effort to educate himself, which was key to his outstanding patriotic action. He was self-taught, like almost all of his classmates. He had a love for culture; he was fascinated with the Bible and even enjoyed reading material by Greek and Roman authors. Historian Juan Daniel Balcácer described Sánchez as tall, with dark skin, a thin build, and extremely circumspect. Possessing a fine sense of humor, he stood out among his friends for his constant smile, always on his lips. He played various musical instruments and enjoyed reciting poetry. According to Eugenio María de Hostos, while educated and having taught himself Latin, English, and French later in life, he is mostly remembered as a man of action.[16]

Rise to Leadership

[edit]Recruitment to La Trinitaria

[edit]

One day, while attending philosophy classes, he was approached by a classmate, Juan Pablo Duarte, who was immediately intrigued by Sánchez's level of intellect. In 1838, Duarte founded the movement La Trinitaria, a nationalistic organization that intends to bring freedom to the Dominican people, who during this time were living in tyranny under Haitian rule. The main objective of this movement was to movement was to not only overthrow Haitian rule, but to establish an independent state free of foreign power. Seeing Sánchez as a perfect candidate for membership, Duarte didn't think twice before recruiting him. Sánchez had traveled to the United States and Europe as a young man. His vision of the cause was the typical republican goal of the Age of Enlightenment.

With his recruitment, it didn't take long for Sánchez to stand out for his industriousness and determination. Little by little, he gained a leading position in the organization, becoming a fundamental figure in the daily work to achieve the objectives that gave rise to it.[1] Eventually, not only would he prove to be a vital asset for the cause, but it would also allow him to earn Duarte's faith in him, placing his full trust on the young revolutionary.

Sánchez's significance is seen in that he was one of those who led the overthrow of the Haitian authorities of Santo Domingo appointed by Jean Pierre Boyer, deposed at the end of March 1843 by the movement called La Reforma. Soon, the Trinitarios and the Haitian liberals took divergent paths, as the former formulated the goal of becoming independent from Haiti.[17]

Upon noticing the rise of independence ideas among Dominicans, Haitian President Charles Rivière-Hérard, who came to power after the triumph of La Reforma, decided to make an intimidating visit to the former Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, known to Haitians as “Partie de L´Est”. Duarte and several of his companions, among whom was Sánchez, hid. The Haitians unleashed a tenacious persecution of the fugitives and Duarte, Juan Isidro Pérez and Pedro Alejandro Pina left the country on August 2, 1843. Sánchez could not do so due to being ill, a circumstance that he took advantage of to direct the conspiratorial tasks, virtually replacing Duarte. He gained the support of relatives of some of his colleagues from La Trinitaria, which made it possible for him to remain hidden for more than seven months, since at all times he rejected the possibility of leaving the country. According to historian Frank Moya Pons, in order to act with fewer difficulties, he spread the rumor that he had died and had been secretly buried in the small cemetery of the Carmen church.[17]

Substitute leader for Duarte

[edit]Juan Pablo Duarte's exile took place at the last and most crucial stage of the struggle. But it was when Duarte was exiled and in hiding in Venezuela that Sánchez became the central presence in the Dominican revolt. In 1843, when Duarte went into exile in Curaçao for fear of being assassinated or imprisoned by the Haitian authorities, Sánchez, then 25 years old, assumed the leadership of the independence movement La Trinitaria, where he presided over the group's meetings and expanded contacts with representatives of the most important social sector in the city, with the collaboration of fellow member Matías Ramón Mella.

Sanchez's revolutionary work was intense. He originally intended to consummate independence at the end of 1843 with only the Trinitarian forces. The objective was an uprising at the end of 1843, for which he sent a letter to Juan Pablo Duarte, which his brother, Vicente Celestino Duarte, also signed, dated November 15, 1843. They asked asked Duarte to arrive along the coast of Guayacanes to put himself at the forefront of the insurrection, and to try to bring weapons. The letter portrays the situation that the efforts in pursuit of independence were going through:[18]

Juan Pablo:

With Mr. José Ramón Chaves Hernández we write to you on November 18, imposing on you the political state of this city and the needs we have for you to (get) help for the triumph of our cause. Now we take advantage of the opportunity of Mr. Buenaventura Freites to repeat to you what we tell you in the others in case they had not reached your hands.

After your departure, all the circumstances have been favorable, so that we only lacked a combination to have delivered the blow. To this date, the business is in the same state in which you left it: for what we ask you, even at the expense of a star from heaven, the following effects: two thousand or one thousand or five hundred rifles, at least: four thousand cartridges, two or three hundred weight of lead; five hundred spears or whatever you can get, the war utensils you can.

About money, you know more than anyone what may he needed; In conclusion what is essential is help, however small it may be, since this is the opinion of the majority of the headless. This achieved, you must go to the port if Guayacanes, always with the concern of being a little removed from land, about one or two miles, until you are notified, or signaled, for which purpose you will place a white pennant if it is daylight and a lantern above the mainmast if it were night.

Once all this has been determined, you will try, if possible, to communicate it to Santo Domingo so that you can go and wait on the coast on December 9, or before, because it is necessary to fear the audacity of a third party or an enemy of ours, the people being so inflamed.

Ramón Mella prepares to go there, although he tells us that he is going to Saint Thomas and it is not convenient for you to trust him, since he is the only one who has harmed us in any way again due to his blind ambition and imprudence.

The National Guard has been ordered to exercise here, and one afternoon, because a soldier had left the line, Mr. Colonel Alfau lashed him, but he miraculously escaped with a bayonet and had the sad disappointment of being almost attacked the entire first battalion and see nothing but his brother Abbot in his defense.

To Juan Isidro Pérez and Pedro Pina, who receive all the expression of affection that we could do if we saw them and that we did not write to them separately due to lack of time.

Juan Pablo, we repeat the greatest activity, let's see if we make the month of December memorable forever.

God, Country and Freedom, Francisco del Rosario Sánchez and Vicente Celestino Duarte.

It is clear from the letter that Sánchez and Vicente Celestino Duarte intended to carry out separation from Haiti relying only on the Trinitario liberal sector. This is how it can be understood that the reproach they leveled at Mella and the haste they required to prevent their rivals from the third party, the French team, from overtaking them. Sánchez wrote a manifesto calling for independence, which was distributed throughout the country, the text of which has been lost. From information that Pedro Alejandro Pina received and transmitted to Duarte, in a letter dated 27 November 1843, it is deduced that the Trinitarios had recovered from Hérard's repression and were gaining strength, while the French supporters were weakening. Pina says to Duarte:[19]

The Duartista party has progressed, receiving life and movement from that excellent patriot, from the moderate, faithful and courageous Sánchez whom we believed in the grave. Ramón Contreras is a new party leader, also a Duartist. That of the French people has weakened to such a degree that only the Alfau and Delgado remain in it; The other supporters, some have joined ours and the others are indifferent. The reigning party awaits you as general in chief, to begin that great and glorious revolutionary movement, which will bring happiness to the Dominican people

A few days after the first letter it must have become clear to Sánchez that the sector he led found it impossible to produce independence on its own and that, therefore, it was imperative to reach an agreement with people of other orientations. In this sense, at the end of 1843 he reoriented himself towards achieving an alliance with a conservative sector, a position that he had criticized Mella shortly before. This way we can understand what Pina conveyed to Duarte, in the sense that some French people had joined the liberals. The basic link in such alliance was Tomás Bobadilla, a lawyer who held positions in public administration since the time of España Boba and who had collaborated with the Haitian regime. Bobadilla, like other figures of social prestige, understood that the crisis in which Haiti's ruling groups were struggling had created the conditions to overthrow their rule. For accidental reasons, Bobadilla had not reached agreements with Buenaventura Báez, the dominant figure among the Dominican representatives in the Constituent Assembly of Port-au-Prince, who established secret negotiations with the consul general of France, Emile de Levasseur, in order for the projected independent state to be constituted as a protectorate of France. Such a project was supposed to materialize through the appointment of a French governor for 10 renewable years, the transfer of Samaná and cooperation with France in the reconquest of Haiti.[20]

Liberals and conservatives were aware of their weaknesses and the importance of an alliance, but the attempts that had been made ended in failure. While Duarte was still in the country, meetings were held in which it became clear that the differences were insurmountable. It was up to Sánchez to break this mutual animosity, following the steps initiated by Mella, when he became convinced that the Trinitarian sector he headed could not declare independence on its own. Although conservative participation was crucial for it to materialize on February 27, all the work was directed by Sánchez and his Trinitarian companions, who had a greater capacity for initiative than the Frenchified group. This primacy made it easier for the Trinitarios to remain compact around Sánchez.[21]

Dominican Act of Independence

[edit]From this alliance, a document was prepared in which both parties called for the creation of the Dominican Republic. The document is titled “Demonstration of the peoples of the Eastern Part of the formerly Spanish Island or of Santo Domingo, on the causes of its separation from the Haitian Republic” and is known as the Manifesto of January 16 due to the date on which it was read for the first time. Four copies were made, one remained in Santo Domingo and the other three were sent to the main regions of the country: Juan Evangelista Jiménez took it to Cibao, to the south, Gabino Puello, and to the east, Juan Contreras. The Manifesto of January 16 was a response to the one prepared by Buenaventura Báez on January 1 of the same year, in which he called for the creation of the Dominican Republic as a protectorate of France. The first, on the other hand, clearly stated the purpose of establishing a fully sovereign State, although it did not mention the term independence but that of separation. Even so, there is no hint of protectionist approaches that would mediate national autonomy. The secret dissemination of the text ended up creating the conditions for Haitian rule to be overthrown.[22]

In one of the paragraphs of the manifesto, Sánchez denotes his firm decision to achieve the objective contained in the Trinitarian oath:[1]

We believe we have demonstrated with heroic constancy, that the evils of a government must be suffered while they are bearable, rather than do justice by abolishing forms; but when a long series of injustices, violations, and insults, continuing to the same end, denote the design of reducing everything to despotism and the most obsolete tyranny, it is the sacred right of the peoples and their duty to throw off the yoke of such a government and provide for new guarantees ensuring its future stability and prosperity and adds: "Twenty-two years ago, the Dominican People, through one of those fatalities of fate, are suffering the most ignominious oppression...

The manifesto, having already been unified by the alliance made between liberals and conservatives, changed the word independence for reparation, culminating these words:[1]

To the Dominican union! Since the opportune moment is presented to us from Neiba to Samaná, from Azua to Montecristi, the opinions are in agreement and there is no Dominican who does not exclaim with enthusiasm: Separation, God, Homeland and Freedom.

Meeting at the house of Sánchez, on 24 February, the members of La Trinitaria discussed on the plans on the uprising, which they agreed would be set for 27 February 1844. A day later, the rebels were sent to various parts of the country for the purpose of finalizing the agreements made during the meeting. In addition to Sánchez and Mella, Vicente Celestino Duarte, José Joaquín Puello, those of La Concha (Jacinto and Tomás), Juan Alejandro Acosta and many others attended that meeting. At the proposal of some of his companions, among whom were Félix Mercenario, Manuel María Valverde, Manuel Jimenes and Mariano Echavarría, it was agreed that Sánchez would preside over the Governing Board that was to direct the destinies of the nascent republic.

In the previous days, the commitment of the officers of the 31st and 32nd regiments, as well as the city garrison, had been achieved. For example, Manuel Jiménes obtained the support of Martín Girón, officer in charge of Puerta del Conde. The plan established that a part of the conspirators would gather at the Puerta de la Misericordia and from there they would converge with others who would go to Puerta del Conde, as a meeting point to assume control of the city and take the Ozama Fortress. Testimonies indicate that many of those committed did not show up at the scheduled time, around midnight on the 27th.

Proclamation of Dominican independence

[edit]

On the night of 27 February 1844, Sánchez and his men raided the Ozama Fortress. The Haitian garrison stationed in the city was caught by surprise, apparently betrayed by one of their sentinels, and was forced to flee the scene. After this, Sánchez marched to the tip of Puerta Del Conde. Mella, who had just arrived in the city, fired his blunderbuss into the air, disturbing the silence. At that moment, Sánchez raised the historical tricolor 1844 independent Dominican flag, shouting at the top of his lungs, the national slogan, Dios, Patria, Y Libertad, (God, Homeland, and Freedom), proclaiming to the world the birth of the new independent nation: The Dominican Republic. A new republic, now free of foreign rule, had now been born in the form of a republican and democratic government. Sánchez was just 26 years old when this took place.[23]

First Dominican Republic

[edit]Central Government Board

[edit]

As agreed, his first act after declaration of independence was to take presidency of the Central Government Board, designed to govern over the nation in the wake of its independence. His first and only task as president was to deal with the mutiny of former slaves, led by Santiago Basora, who grew concerned of the rumor of the alleged reimposition of slavery. As such, Sánchez ordered Bobadilla to go to Monte Grande to assure the freedmen that slavery would not be reinstated. The small Haitian garrison did not dare to offer resistance. He locked himself in the Fortress, from where his leaders began negotiations with the French consul that led to the bloodless capitulation on February 28. The Haitians residing in the city, although they received guarantees that they could become Dominicans, preferred to emigrate. On February 29, apparently of his own free will, Sánchez handed over the presidency of the Board to Bobadilla, in recognition of the role that the conservative sector was called to play from now on, with more social influence than the Trinitarios among the rural population of the interior from the country.[24]

Sánchez had anticipated for his predecessors to follow Duarte's ideals to maintain an independent state free of any foreign power. But these ideas were tossed to the ground due to opposing sides who felt that the new nation was not financially and economy able to withstand on its own, especially in the wake of the upcoming threats by the Haitians. And thus, this began a new era for the Dominican Republic tainted with violent political standoffs. This becane apparent when it was discovered that Bobadilla treacherously carried out actions to achieve a protectorate of France, through the Levasseur Plan, through which French military aid would materialize, to emerge victorious in the war that was looming and in compensation, the new Dominican state would cede the Samaná Peninsula and the Samaná Bay to France.

Angered, the Trinitarios carried out a coup d'état on 9 June and expelled the supporters of the French protectorate, restoring Sánchez in the Presidency of the Governing Board. However, Pedro Santana, at the head of the Army of the South, advanced to Santo Domingo and on 12 July 1844 gave a counterattack, expelling the Trinitarios from the Central Government Board, and the Seibano leader was sworn in as President of the Republic. The young Trinitarios, previously revered as the architects of the Dominican nationalism, had to suffer the most unlikely persecutions, exiles, imprisonments and executions, as well as receive false moral insults with the intention of piercing their lineage. Not a single one of the young Duartistas escaped the cruel campaign of indictments by Pedro Santana and the conservative sectors who assaulted the political command in the nascent republic.

First exile and Return

[edit]

As a sad paradox of fate, six months after the consummation of National Independence, on 22 August 1844, the Central Government Board led by Pedro Santana, issued a resolution declaring the Trinitario chiefs (Duarte, Sánchez and Mella) "traitors to the Homeland” and deported them in perpetuity. Sánchez was exiled to Europe on 26 August 1844, along with Mella. However, tragedy struck while on board the ship, which crashed off the coast of Ireland, killing many of the people on the ship. The survivors, of which included Sánchez and Mella, found themselves in Dublin. In December 1844, they relocated to New York. From there, Sánchez moved to Curaçao. Mella, on the other hand, resettled in neighboring Puerto Rico.

His life in Curaçao was very simple. He settled in the suburb community of Pietermaai, located in the capital city of Willemstad. He took a job as a teacher, where he taught Spanish and other subjects in the company of companions of his friend, Juan José Illás. This allowed him to meet Leoncia Rodríguez, a Curaçaoan woman, with whom he established a romantic relationship, thus conceiving a daughter. However, Sánchez had received the tragic news that his aunt, Maria Trinidad Sánchez, had been tortured and executed by Santana for refusing to name the conspirators against him on 27 February 1845, exactly one year after the independence from Haiti. Sanchez's elder half-brother, Andrés, Nicolás de Barías and José del Carmen Figueroa were also shot.

In 1848, Manuel Jimenes, the newly elected president, granted an amnesty which allowed the return of Sanchez and many of the exiled patriots back to the country. Sanchez returned to the Dominican Republic during a very crucial time. He had returned just in time to find that his parents, Olaya del Rosario and Narsisso Sanchez, were still alive. However, by the beginning of February 1849, Olaya del Rosario became seriously ill. Longing to enjoy her presence, both Sánchez and his father came to an agreement that her end was near. He continued to be by her side until her unfortunate death on 2 March 1849. Before her death, Sánchez reconnected with his old girlfriend, Balbina Peña, later marrying her. The two would remain wed until Sánchez's death. In addition, the widowed Narciso Sánchez would later remarry with Emelie Wincler Pitineli, a native of Curaçao, procreating María Teresa Sánchez Wincler in 1852.

On his return, Sanchez held many important positions in government. He was appointed Commander of Arms for the city of Santo Domingo by Jimenes. However, almost immediately after assuming office, Faustin Soulouque, the new ruler of Haiti, ensued a new invasion into the territory. The head of the Dominican army, Antonio Duvergé, suffered some defeats against the Haitian troops, which was used by Santana's supporters to discredit him and disobey his orders. The population of the city of Santo Domingo fell into panic because they believed that nothing would stop Soulouque. In Congress, Buenaventura Báez promoted the appointment of Santana as head of the army, contravening Jiménes' position. The attempt he made to lead the troops also ended in failure, a victim of sabotage by Santana's faithful. Sánchez accompanied Santana for a few days. However, it seems that differences arose between them for unknown reasons, and by the time the Battle of Las Carreras began, on April 21, Sánchez had retreated towards Santo Domingo. Although he returned to the theater of events as soon as he heard the cannon shots, he arrived after the battle was over.[25] Following the Dominican victory over the Haitians, Sánchez wrote a testimony, in which he writes:[26]

When the invasion of Soulouque began, I was in the capital carrying out the position of Commander of Arms. After I heard the news that the enemy had taken possession of Azua without the expected resistance being put up, seeing that General Santana was going down to the theater of war, I voluntarily asked the Minister of War to Division General Ramón Bidó was then, to replace me in the post I occupied and give me route order to leave with the troops that I could collect, to place myself at the disposal of Generals Pedro Santana and Antonio Duvergé who were the ones who they commanded the army of operations.

I left and stopped three days in San Cristobal to join the battalion of that post commanded by Commander Juan M. Albert. Not having verified the meeting of this body due to the flight from Azua, I continued my march until I reached Baní where I received a written order, from the general in chief of the army Pedro Santana, which I still have, to deliver the troops under my command to Lieutenant Colonel Dionicio Cabral, who was to lead them to Portesuelo where there was the greatest need for them. Conforming to the chief's orders as I should, I verified said delivery the same day I received the order and always continued until I reached the presence of General Santana, who was in Sabana Buey.

That same night our troops deserted the post of Number, which was Thermopylae of the Republic. General Duvergé, who had sustained a heroic combat that same day, and who was that same night in the company of General Santana, before receiving the news that the troops under his immediate command had deserted the post in his absence, can say how much I begged him to take me in his company and return to Number, whose place was at that moment the point of combat, but this warrior was broken in his health due to the fatigue of the war, and he withdrew to the town of Baní.

It was then that General Santana, apart from the salutary measures he had already taken to improve the order of the campaign, began his ingenious and happy operations on the Las Carreras field, incorporating into the army of action even his own guard for the night. Shortage of troops, and all of them headed a forced march under the command of Generals Merced Marcano, Bernardino Pérez and Abad Alfau, to conquer in the field of Las Carreras under the immediate command and in the presence of General Santana, the unfading laurels that they must crown the temples of the liberators of the Homeland.

General Ricardo Miura is dead, but General Pascual Ferré is alive, and many others who witnessed what I am going to refer to: I complained to General Santana that due to my rights of seniority, he should entrust me with the command of a division that was going to fight. I reiterated this claim, there where lies are not spoken; there where the colors of the enemy flags could be distinguished, but General Santana answered me that he wanted me to be in his company and he repeated these same words in his memorable proclamation to the army in Las Carreras field. I remained like this for many days (barely four days had elapsed from the combat between Nùmero and Las Carreras, and Santana arrived at the latter place on the eve of the battle) until, for reasons that are not of the moment to state, I took my passport from General Santana for the capital.

On my march I stopped at Baní, and as soon as the enemy's cannonade was distinguished in this town, I prepared myself and made a countermarch early, accompanied by Colonel Tabera to rejoin General Santana, but the provisions that he had taken were so accurate that the presence of the enemy in the field and its destruction was the strike of lightning.

Sánchez even addressed to the nation, in regards to Santana's resounding victory with following:[26]

But who would believe it! They didn't even publish the reports that I gave announcing the triumph; and if they published it after weeks, devoured by a shameful envy, they maliciously concealed our name.

Even though four years earlier Santana had had his aunt and brother murdered, at that moment Sánchez was careful not to harass him. He was forced to agree with the prevailing conservative politics as a price to remain in the interior of the country. However, he refused to support the coup d'état led by Santana against President Jiménes, and preferred to retire from political life to practice the profession of lawyer or public defender. It is true that, during the brief second administration of Santana, in 1849, Sánchez accepted the position of fiscal attorney of Santo Domingo, a position in which he was forced to be the accuser of General Antonio Duvergé in the first submission to trial that Santana made of him., who had taken a dislike to him for having opposed the coup d'état. Sánchez and Duvergé remained friends, despite this hateful act by Santana.[27]

Moved by this cautious attitude, and although retired from the practice of the profession, in 1853, Sánchez published the article Amnesty, in which he congratulated Santana for his willingness to allow the return of all those politically persecuted as a result of taking the presidency by third time, and elevated him to the status of the nation's greatest hero. Sánchez's decision to praise Santana has earned him harsh criticism. Without a doubt, Sánchez resigned himself to inserting himself into the existing order of things, but this does not mean that he abdicated his essential positions in national objectives. He seems to have reached the conclusion that the country was not prepared for a democratic order and that feasible goals had to be guaranteed, above all safeguarding the independence of the Republic.[28]

1853–1859: Alignment with Báez, second exile and Cibaeño Revolution

[edit]

However, by 1853, relations between Sánchez and Santana reached a breaking point when Santana succeeded in expelling Buenaventura Báez from the country. This resulted into a fierce struggle between the two politicians, of which Sánchez, like Duvergé, sided with the latter. During this time, Baecism had gained the support of all those who had become adversaries to Santana's growing despotism. Báez supporters consisted mostly of young, educated people with liberal convictions from the city of Santo Domingo. To Sánchez, he saw this side much too familiar to that of his political stance, which allowed him to compromise with Báez upon realizing that Santana's authority could be questioned. He had to consider his decision to enter politics again, because he was permeated – and would continue to be until his death – with an acute feeling of disappointment. But the sense of duty and the vocation to give everything for the good of the country, the maximum garments of its greatness, were stronger.[28]

Around this time, Sánchez was approached by Pedro Eugenio Pelletier and Pedro Ramón de Mena, conspirators who organized a group seeking to overthrow Santana and reinstall Báez as president. Earlier on 25 March, a rebellion that aimed to overthrow Santana failed. Apparently, Duvergé was involved in that conspiracy. As a result, Duvergé, his 23 year old son, Tomás de la Concha, and many others were executed on Santana's orders on 11 April 1855. When this failed, Sánchez would be exiled to Curaçao for the second time. There, he established a strong relationship with Báez, who realized the importance of being supported by someone of stature such as Sánchez.[29]

Báez's return was facilitated by the agreement he reached with the Spanish consul, Antonio María Segovia, while he was in exile in Saint Thomas. Segovia's belligerence was due to the fact that Santana was oriented toward annexation to the United States, a purpose that began to be outlined through a treaty through which the Samaná peninsula was leased. And if the Dominican Republic fell under North American tutelage, as was Santana's interest, Spain's interests in Cuba would be affected. In order to undermine Santana's rapprochement with the United States, Segovia established that all Dominicans who wanted to could become Spanish citizens. The Baecistas took advantage of the opportunity to protect themselves behind their status as Spanish subjects and carry out an opposition without taking risks. This created a state of affairs that Santana couldn't control.[29]

He would be allowed to return in August 1856, when Santana resigned, and Manuel de Regla Mota took office as the new president. When Baez returned to office for a second term, Sánchez prepared to support him to expel Santana's influence over the nation. However, when considered for candidacy, Sánchez rejected, believing that Baez made a better candidate. With his presidency, he appointed Sánchez as governor of the province of Santo Domingo and even Commander of Arms for the city, although Sánchez would retain this position in discreet. Interestingly, when José María Cabral took Santana prisoner to Santo Domingo, to later deport him to Martinique, Sánchez allowed Santana to stay at his residence, and even treated him with compassion.[29]

On 7 July 1857, Báez faced an uprising Santiago due to the issue of a large quantity of paper money that was used to purchase tobacco crop. This action gave an uneasy feeling to politicians in the Cibao, who felt that the government did not satisfy their interests. Over the next few days, nearly the entire nation adhered to the provisional government led by José Desiderio Valverde. But despite this, the troops were unable to attack the city.

Fortunately for Santana, this allowed him to regain his political status and even gave him the leadership that surrounded Santo Domingo, still recognizing Santana's military capacity. The siege on the city carried on for nearly a year, though Santana refrain launching a counterstrike; a large portion of the city's population were in favor, of which included Sánchez, and Cabral. Both men were placed as the city's head of defense, where each launched their own offensive methods that took them to Majorra a few days after the outbreak of the Cibaeño Revolution. He would later resign from his position and, as agreed by ability parties, he would be allowed to remain in the country without persecution. He continued his life as a lawyer, away from political affairs.

On 28 April 1859, he was suspended for one month by the court "due to alleged lack of reverence and other misdeeds committed against the judiciary." He was later rehabilitated on 16 May by the Supreme Court of Justice. One of the most significant events of his career took place on 12 August 1859, in a high profile case involving a charge of adultery against Víctor George, an artillery captain with the rank of lieutenant colonel. A month earlier, on 4 July, George had returned home to find his wife in the arms of another man, and in a jealous rage, he fired his pistol at the pair. His wife later died of her injuries, while her lover was injured but survived. Sánchez assumed George's defense, displaying his skills as a lawyer, and finished his closing argument with the following words:[30]

Magistrates, today you are going to rule on a cause célèbre, as should also be your decision. Once the fact is established the law cries aloud for the acquittal of Victor George. Do not forget that the inconceivable condemnation of the accused, in addition to being unjust, would have a serious drawback, which would be to encourage lustful behavior. Besides being just, his acquittal would have one advantage: that of strengthening women's respect for their husbands.

The case ended with George's acquittal, and Sánchez was carried out of the court on the shoulders of the excited audience. (Upon learning of the Sánchez expedition in the south, Victor George left on foot to take part in the struggle in a gesture of gratitude, but was killed near the city of Azua by Pedro Santana's supporters).

Annexation to Spain

[edit]1859–1861: Banishment and annexation

[edit]

However, it was during this period that political and economic disorder plagued the Caribbean nation. With the Dominican War of Independence coming to a close, the country had inherited a serious amount of debt due to Santana's heavy spending of the wars, as well as the bankrupted treasury left behind during Báez's time in office. Santana's misrule of the power combined with Báez corrupt regime left a devastating effect on the nation's economy. This, along with consistent fears of another attack from the Haitians, gave justification for the nation to be annexed to a foreign power.

Sánchez, who had been under surveillance for months following the revolution, was suspected of taking part of a renewed conspiracy against Santana's government, once again with the purpose of restoring the power back to Baez. Although this time, Sánchez did not take part in this group. But despite this, however, Santana considered his overall presence as a serious threat to his administration, who during this time was currently in negotiations with Spain to re-annex the country, an act of which Santana was aware that Sánchez would've strongly opposed. Therefore, for the third and final time, in 1859, Sánchez was exiled and banished from the country, this time to Saint Thomas. He settled in the main town of Charlotte Amalie, where his existence was full of privations, surviving practically in a state of destitution and much of the time, battling illness.[31]

Ultimately, in 1861, Santana struck a deal with Spain to reintegrate the Dominican Republic back to colonial status in exchange for honorary privileges. Learning of this action, Sánchez was outraged and immediately took lead of the opposition to confront this. Báez, on the other hand, decided not to take part in the opposition, believing that the annexation was inevitable, and once consummated, the conflicts between the Spanish and Santana would only intensify, giving Santana more opportunities to attain commanding positions. From this moment, Sánchez severed all ties Báez, reverting him back to his Trinitario origins, giving him the renewed stature of a hero who embodied the ideals of freedom. However, Báez left his supporters free to do as they please, since he could not prevent them from taking part in stopping the annexation. In addition, Báez's lieutenants also accepted Sánchez's leadership.[32]

Dominican Revolutionary Board and Haiti

[edit]

Returning to Curaçao, Sánchez set the structure for the purposes. He ordered a formation called the Dominican Revolutionary Board, of which his part was composed chiefly of Baecistas such as Manuel María Gautier and Valentín Ramírez Báez. The second figure of the movement was led by Cabral, who despite being a supporter of Báez, had always maintained his ideals of independence of judgment, along with liberal and national position, of which has shown through his subsequent evolution. Also on board of the movement was his old comrade and fellow Trinitario, Pedro Alejandrino Piña, who had always stood firm on all national struggles.[32]

But without resources, there was little he could do. During this time, he attempted to gain support from various other countries but to no avail. Faced with no other choice, Sánchez ended up traveling to Haiti, where he asked president Fabre Geffrard for support to liberate the Dominican Republic from Spanish neocolonialism. (Geffrard, despite leading the revolt that led to Faustin Soulouque's fall from power, had previously acted as one of Haiti's commanding leaders during the Dominican War of Independence). Geffrard's cabinet was divided between a sector hostile to the Dominicans and another that understood that the time had come to respect their decision to live apart from Haiti. In this last position, the Minister of Police, Joseph Lamothe, distinguished himself. But Lamothe's position was a minority, so Sánchez was forced to present, on March 20, a memorandum to the two ministers with whom he was negotiating, in which he explained his conceptions of what cordial relations between the two countries should be: two sovereign nations that divided the island, with full recognition of one another's existence. A family tradition states that in the interview he had with the Haitian president, Sánchez told him the following:[33]

President, I was the instrument used by providence in 1844 to shake Haitian domination and create an independent republic.

But, I did not do it out of hatred, some ignoble feeling or due to ideas of social concern, but because I believed that we constituted two peoples with different characters in all orders, that we are two different peoples that can form separate States, and that the island it is large and beautiful enough to be shared between us, dividing the domain of it. In addition, I in a certain way consolidate with my action the independence of Haiti, because once we achieved the success of our cause, we would celebrate a treaty that guaranteed our mutual independent life.

It would not be so, when Spain, a power of the first order, possesses the eastern part of the island with danger for you. Santana is going to annex Santo Domingo to Spain and I come to prevent this crime, preventing it, I affirm my work and guarantee yours. That is why I have come to ask you to pass the borders and resources with which to prevent the annexation that is planned to be carried out.

Although initially skeptical, he eventually agreed to give aid to the rebels due to the possibility of Spain stretching its power to the rest of the island. It was agreed that he would leave Haiti and return secretly, so that the Haitian government would not be committed to the expedition he was going to carry out. In addition to permission to use its territory, the Haitian administration agreed to provide weapons to the Dominican revolutionaries.[34] With this, he managed to recruit other exiled Dominicans and obtain resources to organize a force of 500 men. This expedition would later be referred to as the Dominican Regeneration Movement.

Final manifesto of 1861

[edit]Before entering the Dominican Republic, he published his final manifesto on 20 January 1861.[35] In it, he addressed a proclamation to his enemies, publicly denouncing Santana's actions, his firm stance to confront the invading Spanish army, and calling on the Dominicans to take up arms against the upcoming threat that was approaching. The full text of that manifesto is as follows:

DOMINICANS!

The despot PEDRO SANTANA, the enemy of your liberties, the plagiarist of all tyrants, the scandal of civilization, wants to perpetuate his name and seal your shame forever, with an almost new crime in history. This crime is the death of the Homeland. The Republic is sold abroad and the flag of the cross, very soon, will no longer waver over your fortresses.

I have believed that I am fulfilling a sacred duty, putting myself in charge of the reaction that prevents the execution of such criminal projects and you must conceive, of course, that, in this revolutionary movement, there is no risk to national independence or your liberties, when organized by the instrument that Providence used to raise the first Dominican flag.

I would not make you this reminder that my modesty rejects, if I were not compelled to do so by circumstances; but you are well aware of my patriotic sentiments, the rectitude of my political principles and the enthusiasm that I have always had for that country and for its freedom; and, I do not doubt it, you will do me justice.

I have set foot on the territory of the Republic, entering through the territory of Haiti, because I have not been able to enter through another part, thus requiring the good combination, and because I am convinced that this Republic, with whom yesterday when it was an empire, we were fighting for our nationality, is today as committed as we are, that we preserve it thanks to the policy of a republican cabinet, wise and just.

But, if the slander seeks pretexts to sully my conduct, you will respond to any charge, saying out loud, although without boasting, that I AM THE NATIONAL FLAG.

COMPATRIOTS! The chains of despotism and slavery await you: it is the present that Santana gives you to give himself up to the peaceful enjoyment of the price of you, your children and your property: reject such outrage with the indignation of a free man, giving the cry of rebuke against the tyrant. Yes, against the tyrant, against Santana and only against him. No Dominican, if anyone accompanies him, is capable of such a crime unless he is fascinated.

Let's do justice to our Dominican race. Only Santana, the traitor par excellence, the instinctive killer, the eternal enemy of our freedom, the one who has taken over the Republic, is the one who has an interest in this shameful traffic—he is the only one capable of carrying it out to put himself in charge. Except for his evils—he alone is responsible and a criminal for crimes against the country.

DOMINICANS! To the weapons! The day has arrived to save, forever, freedom: come; Don't you hear the cry of the afflicted Homeland that calls you to its aid? Fly to her defense, save that favorite daughter of the tropics, from the ignominious chains that her discoverer took to the grave. Show yourselves worthy of your country and of the century of freedom.

Prove to the world that you are part of the number of those indomitable and warlike peoples who admit civilization by customs, enjoyment with impairment of their rights, because those enjoyments are golden chains that do not mitigate the weight, nor erase the infamy.

DOMINICANS! To the weapons! Overthrow Santana: overthrow the tyranny and do not hesitate to declare yourselves free and independent, hoisting the crossed flag of twenty-seven and proclaiming a new government that will reconstitute the country and give you the guarantees of freedom, progress and independence that you need.

Down with Santana!

Long live the Dominican Republic! Long live freedom!

Live the independence!

— Francisco del Rosario Sánchez

As declared in the manifesto, which had been signed by Sánchez, it gave an indisputable clarion call about the Santana's treasonous act against the Dominican Republic. Sánchez was aware that Santana carried out his plans through various means. Firstly, when previous annexation attempts, Santana shifted his attention to another powerful nation for a possible protectorate or annexation project, the United States. But due to internal conflicts, (which quickly escalated into the American Civil War), these plans were suspended. Secondly, Santana was forced to turn his gaze towards Spain, which still maintained two vital possessions in the Caribbean: Cuba and Puerto Rico. In the previous decade, attempts for the recognition of the independence of Dominican Republic by Spain ended in failure. In addition, once a plan for a protectorate failed, General Felipe Alfau insteaded proposed an annexation project.[36]

Nevertheless, all of this, in addition to Santana's growing despotism, convinced Sánchez that the nation was in danger of sucumbing into another annexation project. The early inclinations, (even before the project was finalized), pushed Sánchez to rush into action. In fact, in another letter, written to Damián Báez, on 16 January, four days earlier, Sánchez firmly asserts:

My country is sold. This is enough.

With his mission now set, Sánchez returned to Saint Thomas, while his followers congregated in Haiti, coming from Saint Thomas to Curaçao. His plans also won support from Dominican soldiers who had arrived in Haiti a short time before, such as Domingo Ramírez and Fernando Tavera. The Baecista leaders, however, preferred to remain in Port-au-Prince.[32]

Capture and Execution

[edit]Entrance to Dominican Republic

[edit]

Entering through Hondo Valle, (in the province of present-day Elías Piña), on 1 June 1861, Sánchez led his force in an attempt to overthrow Santana, making his way towards Santo Domingo. The expedition was divided into three bodies. The center was led by Sánchez and entered the Hondo Valle area in order to attack San Juan from the east. The second corps was led by José María Cabral and entered through Comendador, with the mission of attacking San Juan from the west. The third corps was under the command of Fernando Tavera and had to take Neiba, where the veteran general was from. He was going to protect that flank and then lead part of his forces in support of Sánchez. In addition, the expedition had the support of Haitian militiamen from Mirebalais and Hincha (now Hinche), areas close to the border. It is not clear why these militiamen were mobilized, although it was probably at the initiative of the Haitian government.[34]

Tabera encountered difficulties, as he was unpopular in the Neiba Valley due to his authoritarian inclinations and his defection towards Haiti the previous year. Instead, Sánchez obtained the support of influential people from the Sierra, among whom Santiago de Óleo stood out. For this reason, he found no obstacles, crossed El Cercado and was able to advance to Vallejuelo with the intention of falling on San Juan. For his part, Cabral took Las Matas de Farfán without encountering much obstacle and was preparing to advance on San Juan.[37]

Meanwhile, Cabral received information that the Haitian government had decided to withdraw support for the Dominican revolutionaries, forced by threats from a Spanish squadron that was stationed in the bay of Port-au-Prince. Faced with this situation, he proceeded to turn back without waiting for Sánchez's order. A few of his subordinates requested permission to go to El Cercado to notify Sánchez. Upon receiving the news, Sánchez also decided to back down, even though he considered the possibility of ignoring the decision of the Haitian regency. Surely, Cabral's hasty action compelled him to order a retreat.[37]

But Sánchez was unaware that the inhabitants of El Cercado, who had previously allied with him, also withdrew their support. They had considered themselves lost in the face of the failure of their enterprise, and resolved to save themselves from the punishment of the government. This act would ultimately seal Sánchez's fate. As Sánchez left for Haiti, he was stunned that Santiago De Oleo was not present.[38] As for de Óleo, he knew the exact route where Sánchez and his companions would take, and thus he set an ambush for him.

As there were no Spanish troops in the area, Sánchez and his companions advanced confidently, but they were surprised by an ambush set by de Óleo on the Juan de la Cruz hill, near Hondo Valle, on June 20. The men put up a struggle, but unfortunately, several of the patriots died instantly, others were able to escape, some of them wounded, while the rest, a last group of 20 among whom many were wounded, were taken prisoner. In the scuffle, Sánchez was wounded in the leg and groin, and was offered a horse by Timoteo Ogando to take him back to Haiti. Sánchez, however, refused this, and was ultimately captured as well. The patriots were taken to San Juan, where Santana ordered that they be tried. In reality it was a prefabricated trial, since from Azua, Santana directed everything that happened in San Juan. The second corporal Antonio Peláez de Campomanes, the most senior Spaniard in the government, opposed the trial because he perceived that the death sentence of the captured expedition members was going to constitute a disastrous precedent that would undermine the prestige of Spain.[37]

Military Trial

[edit]The War Council was headed by General Domingo Lazala and five other officers. The prosecutor was Colonel Tomás Pimentel and the secretary, Alejo Justo Chanlatte. The defenders of the defendants were Cristobal José de Moya and Banilejo José Soto. During the trial, it was clear that it lacked probity. Suffering from serious injuries, the embittered Sánchez tried to shift the entirety of the expedition solely on his shoulders in hopes that the lives of his followers be spared in exchange for his, but to no avail. His defense was very powerful; believing that his actions could not be judged under Dominican law, let alone Spanish law, the latter of which Sánchez argued, hadn't been enforced.In the middle of the trial he rebuked one of his accusers, Romualdo Montero, who had been one of the traitors in Hondo Valle, for which the authorities arrested him and added him to Sánchez and his companions. He also rebuked Judge Lazala, accusing him of holding grudges against him for personal reasons.[39] The full text of his defense is as follows:[40]

Presiding Judge: I know that everything is written.

From this moment I will be the lawyer of my cause. You, Domingo Lazala, appointed to judge my cause, try in vain to humiliate me. I regret having to remind you in public that I was your defense attorney before the Santo Domingo courts and got you acquitted when you were charged as the alleged perpetrator of the murder of one of your relatives from Cibao.

When a faction rises up against any order of the established government, it is the duty of that government to approach that faction until it investigates the reason for its protest. If this has a legitimate basis, its reasons must be addressed and, when not, the factions should be punished according to law.

I come to the country with the firm purpose of asking whoever I should if they have consulted the desire of the Dominicans to annex the Homeland to a foreign nation. By what laws shall I be judged?

With the Spanish ones that have not begun to govern, since the protocol establishes an interregnum of months for the laws of the Kingdom to begin to govern, or with the Dominican ones, which send me to support the independence and sovereignty of the Homeland?

Under what law are we charged? Under what law is the death penalty requested for us? Invoking Dominican law? Impossible. Dominican law cannot condemn those who have not committed another crime other than wanting to keep the Dominican Republic. Invoking Spanish law? You have no right for it. You are officers of the Dominican army. Where is the Spanish code under which you condemned us?

Is it possible to admit that in the Spanish Criminal Code there is an article by which men who defend the independence of their country must be sentenced to death?

But I see that the prosecutor is asking for the same thing for these men as for me, capital punishment. If there is a culprit, the only one is me. These men came because I conquered them.

If there is to be a victim, let it be me alone... I was the one who told them that they had to fulfill their duty to defend Dominican independence, so that it would not be stolen. So, then, if there is a death sentence, let it be against me alone.

I have overthrown your accusation, prosecutor. To fly the Dominican flag it was necessary to shed the blood of the Sánchez family; to lower it, the Sánchez family is needed.

Since my destiny is resolved, let it be fulfilled. I implore the clemency of Heaven and I implore the clemency of that exalted First Queen of Spain, Doña Isabel II, in favor of these martyrs of the Homeland… for me, nothing; I die with my work.

In another account, Sánchez was also quoted with saying:

Tell the Dominicans that I die with the Homeland, for the Homeland, and to my family not to remember my death to avenge it.

Despite his temperance, Sánchez could not help but experience moments of bitterness. This is what the letter explains to his wife, Balbina Peña, advising her to ensure that their children do not enter politics and dedicate themselves to commerce outside the country. In order not to be complicit in the ignominy, one of the commanders of the Spanish troops that had arrived in San Juan days before, Antonio Luzón, decided to leave with his battalion in the direction of Juan de Herrera to carry out exercises.[39]

Execution

[edit]

According to Moreta Castillo, the priest Narciso Barrientos gave the last communion to Sánchez, and as he did so, Sánchez recited verse 6 of Psalm 50: "Tobi soli peccavi et malum coram te feci" (Here is the one who has only sin and has done you wrong). As he was led to the scaffold in a sedan chair, the wounded patriot recited Psalm 50: Miserere, asking God for mercy. Before he was shot, Sánchez asked the young Avelino Orozco to help him to be wrapped around the Dominican flag, and as he heard the command "Fire," Sánchez, with all his might, shouted even louder: "Finis Poland!" (Finish Poland). This was alluding to the end of the republic and evoking Polish patriot Tadeusz Kościuszko, hero of the Battle of Maciejowice in 1794. Sánchez, two-time hero and founding father of the Dominican Republic, was shot dead on 4 July 1861, in San Juan de la Maguana, at the young age of 44. Sánchez, like several of his companions, died with the first shot. Others were not that lucky and were finished off with machetes and clubs. The annexationist generals Eusebio Puello and Antonio Abad Alfau watched the savage execution, impassive.[39] Among others sentenced to death were: Félix Mota, Domingo Piñeyro Boscán, Rudecindo de León, Francisco Martínez, Julián Morris y Morris, Juan Erazo, Benigno del Castillo, Gabino Simonó Guante, Manuel Baldemora, José Antonio Figueroa, Pedro Zorilla, Luciano Solís, José Corporán, Juan Gregorio Rincón, José de Jesus Paredes, Epifanio Jiménez (or Sierra), Juan Dragon, León García, and Juan de la Cruz.

Aftermath

[edit]

The execution of Sánchez sent shockwaves throughout island. It sent a clear message to the patriots of the fate of anyone who dared to challenge Spanish rule. However, the struggle for independence continued to mount as a new era of patriots would arise and join the cause, thus triggering the interlude for the Dominican Restoration War.

Following Sánchez's death, his sister, Socorro was exiled to St. Thomas for two years. When she returned to the Dominican Republic in 1863, she was imprisoned for a year for outspokenness against the regime.[41]

Gregorio Luperón, a then 22-year-old patriot from Puerto Plata, expressed his opposition of the Spanish presence in Dominican Republic, and was arrested. However, he managed to escape from prison and sought refuge in the United States, and later Haiti. He returned to the country through Monti Cristi, where he would begin his revolt against Spanish rule, and Pedro Santana, who at this point was now ruling the country under military dictatorship, in support of Spain.

Duarte, hearing of the country's annexation to Spain, returned to his homeland once to take part in the struggle for independence. Mella, despite his financial crumble and illness, also joined in the cause to liberate the Dominican Republic from Spain.

Eventually, these actions, as well as those of many others paid off. In 1865, Queen Isabella II, realizing that she could not fare off against the Dominicans, withdrew her support and called off her remaining troops from the country, thereby restoring the nation's independence and ending the last Spanish threat to the Dominican Republic. Sánchez never lived to see this transpire.

Legacy

[edit]

Sánchez's legacy is forever engraved into the memory of the Dominican Republic. His contributions to politics, nationalism, and ideals of an independent Dominican state marked him as a true icon for the nation. Some historians have credited him as the true father of the nation due to his status as the leader of the independence movement following Duarte's exile in Venezuela. Many Dominicans even consider him to be the strongest of the Founding Fathers. Brave, honest, bold, and brash, Sánchez's qualities set him apart from many patricians, making the honorable act of sacrificing his life for the nation. Manuel Rodríguez Objío, a young poet who greatly admired Sánchez, once wrote:[42]

Creator of the Dominican nationality and first soldier of independence, he died with the nationality and with the independence of the Homeland. Heroic and great when he was born as a public man in 1844 and great when he died in 1861. He shone in the east of his tempestuous life and descended into the sunset with majesty and light, bequeathing to the generations that succeed him the growing reflection of his glory, a sublime example to the patriots […]. Obscured or outlawed, wandering and persecuted by all tyrants, Sánchez was the father of the country and at the same time its scapegoat. The last moment of that great and unfortunate man was more solemn because it coincided with the agony and death of a nationality. Like Christ, he was clapped and blessed in the Dominican Jerusalem in the year 44. He listened for short days to the Hosanna of his people […]. Later he had his passion and his ordeal, having breathed his last and fallen with the cross of national redemption.

In 1875, Sánchez's remains were exhumed and taken to the Primada de América Cathedral, thus beginning the Chapel of the Immortals. Later, in 1944, they were taken to the Puerta del Conde, together with those of Duarte and Mella. Since 1976, those venerable ashes rest in the sacred mausoleum - an extension of the Panteón de la Patria - which is located in the Parque Independencia in the city of Santo Domingo.

- He is entombed in a mausoleum, Altar de la Patria, at the Count's Gate (Puerta del Conde) alongside Duarte and Mella, at the location of the start of the War of Independence.

- In the province of Samaná, the city of Sánchez is named in his honor.

- Many schools in the Dominican Republic are named in his honor.

- Streets in many parts of the Dominican Republic are named after him.

- A neighborhood in Santiago de Los Caballeros is named in his honor.

- In San Juan de la Maguana, (in the province of present-day San Juan), the location where Sánchez was executed, a park is named after him along with a memorial statue dedicated to his legacy.

- Sánchez is solely depicted on the 5 Dominican peso note and coin; he is also depicted on the 100 Dominican peso note alongside Duarte and Mella.

- A national anthem titled "Himno a Francisco del Rosario Sánchez" is dedicated to his legacy.

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Francisco del Rosario Sánchez[43] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Juan Pablo Duarte

- Matías Ramón Mella

- Socorro Sánchez del Rosario

- María Trinidad Sánchez

- Pedro Santana

- Tomás Bobadilla

- Buenaventura Báez

Notes

[edit]- ^ All sources of the time describes Olaya del Rosario as having a white appearance. However, because of her Canarian ancestry she was not legally white during colonial times, as Canarians were not deemed as Peninsulares and were legally classified by Spanish colonial authorities as "Pardos" unless they could prove with genealogical data that they did not had Guanche blood in order to obtain a Limpieza de Sangre certificate (a sort of "White certificate" that used race and religion as parameters).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Tejeda, Karil. "Sánchez, Padre de la Patria". Diario El Matero (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ Boletín del Archivo General de la Nación. Volumen 14. 1951. Pages 413-417

- ^ Amador, Luis; Hidalgo, Dennis R. (2016). "Sánchez, Francisco del Rosario (1817–1861), political and military leader". In Knight, Franklin W.; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.). Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro–Latin American Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-93580-2. – via Oxford University Press's Reference Online (subscription required)

- ^ Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio (1976). Acerca de Francisco del R. Sánchez [About Francisco del R. Sánchez] (in Spanish). Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Editora Taller. p. 9. OCLC 1025652086.

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, hijo de Narciso Sánchez y de Olaya del Rosario, "parda libre". Legitimado por matrimonio posterior, en 1819 [Francisco del Rosario Sánchez was born, son of Narciso Sánchez so one time i married a hoe she was ugly ario, free parda. Legitimated by subsequent marriage, in 1819.]

- ^ Cassa, Roberto (2008). Padres de la Patria (in Spanish). Santo Domingo: Alfa y Omega. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9789945020380.

- ^ Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio (1976). Acerca de Francisco del R. Sánchez [About Francisco del R. Sánchez] (in Spanish). Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Editora Taller. p. 9. OCLC 1025652086.

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, hijo de Narciso Sánchez y de Olaya del Rosario, "parda libre". Legitimado por matrimonio posterior, en 1819 [Francisco del Rosario Sánchez was born, son of Narciso Sánchez so one time i married a hoe she was ugly ario, free parda. Legitimated by subsequent marriage, in 1819.]

- ^ González Hernández, Julio (11 March 2017). "Cápsulas genealógicas. Sánchez genealógico" [Genealogical Capsules: Sánchez Genealogy]. Hoy (in Spanish). Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 211. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Instituto Dominicano de Genealogía, Inc. - Victor Arthur". www.idg.org.do. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ "Instituto Dominicano de Genealogía, Inc. - Victor Arthur". www.idg.org.do. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ Suazo, Publicado por S. Aquiles Ramirez. "FAMILIA SANCHEZ I I". Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Pichardo, José del Castillo (2008-10-11). "Con la Música por Dentro". Diario Libre (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ "Instituto Dominicano de Genealogía, Inc. - Victor Arthur". www.idg.org.do. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ "Juan Daniel Balcécer". Juan Daniel Balcácer (in Spanish). 2017-03-09. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Saba, Ramón (2019-04-04). "Enriquillo Sánchez". El Nuevo Diario (República Dominicana) (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Cassá, Roberto (2008). Padres de la Patria (in Spanish). Santo Domingo: Alfa y Omega. p. 46. ISBN 9789945020380.

- ^ a b Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 213. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 214. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 215. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 216. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 217. ISBN 9789945586046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cassá, Roberto (2002). Francisco del Rosario Sánchez: fundador de la República (in Spanish). Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Alfa & Omega. ISBN 9789993476542.

- ^ Cassá, Roberto (2014). Personajes Dominicanos [Dominican Characters] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Santo Domingo. p. 220. ISBN 9789945586046.