Truman Capote

Truman Capote | |

|---|---|

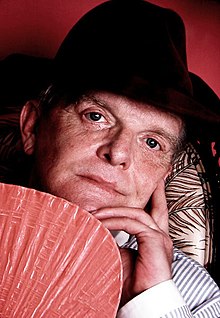

Capote in 1980 by Jack Mitchell | |

| Born | Truman Streckfus Persons September 30, 1924 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | August 25, 1984 (aged 59) Los Angeles, California |

| Resting place | Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Other names | Truman Garcia Capote |

| Education | Greenwich High School Dwight School |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1942–1984 |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement |

|

| Partner | Jack Dunphy (1948–1975) |

| Signature | |

Truman Garcia Capote[1] (/kəˈpoʊti/ kə-POH-tee;[2] born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright, and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, and he is regarded as one of the founders of New Journalism, along with Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, and Tom Wolfe.[3] His work and his life story have been adapted into and have been the subject of more than 20 films and television productions.

Capote had a troubled childhood caused by his parents' divorce, a long absence from his mother, and multiple moves. He was planning to become a writer by the time he was eight years old,[4] and he honed his writing ability throughout his childhood. He began his professional career writing short stories. The critical success of "Miriam" (1945) attracted the attention of Random House publisher Bennett Cerf and resulted in a contract to write the novel Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948). He achieved widespread acclaim with Breakfast at Tiffany's (1958)—a novella about a fictional New York café society girl named Holly Golightly, and the true crime novel In Cold Blood (1966)—a journalistic work about the murder of a Kansas farm family in their home. Capote spent six years writing the latter, aided by his lifelong friend Harper Lee, who wrote To Kill a Mockingbird (1960).[5]

Early life

[edit]

Truman Capote was born at Touro Infirmary in New Orleans, Louisiana, to Lillie Mae Faulk (1905–1954) and salesman Archulus Persons (1897–1981).[2] He was sent to Monroeville, Alabama, where, for the following four to five years, he was raised by his mother's relatives. He formed a fast bond with his mother's distant relative, Nanny Rumbley Faulk, whom Truman called "Sook". "Her face is remarkable – not unlike Lincoln's, craggy like that, and tinted by sun and wind", is how Capote described Sook in "A Christmas Memory" (1956). In Monroeville, Capote was a neighbor and friend of Harper Lee, who would also go on to become an acclaimed author and a lifelong friend of Capote's. Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird likely models Dill's characterization upon Capote.[6][7][8]

As a lonely child, Capote taught himself to read and write before he entered his first year of school.[9] Capote was often seen at age five carrying his dictionary and notepad, and began writing fiction at age 11.[10] He was given the nickname "Bulldog" around this age.[11]

On Saturdays, he made trips from Monroeville to the nearby city of Mobile on the Gulf Coast, and at one point submitted a short story, "Old Mrs. Busybody", to a children's writing contest sponsored by the Mobile Press Register. Capote received recognition for his early work from The Scholastic Art & Writing Awards in 1936.[12]

In 1932, he moved to New York City to live with his mother and her second husband, José García Capote. José was a former Spanish colonel who became a landlord at Union de Reyes, Cuba.[13]

Of his early days, Capote related, "I was writing really sort of serious when I was about eleven. I say seriously in the sense that like other kids go home and practice the violin or the piano or whatever, I used to go home from school every day, and I would write for about three hours. I was obsessed by it."[14] In 1932, he attended the Trinity School in New York City. He then attended St. Joseph Military Academy. In 1939, the Capote family moved to Greenwich, Connecticut, and Truman attended Greenwich High School, where he wrote for both the school's literary journal, The Green Witch, and the school newspaper. When they returned to New York City in 1941, he attended the Franklin School, an Upper West Side private school now known as the Dwight School, and graduated in 1942.[15] That was the end of his formal education.

While still attending Franklin in 1942, Capote began working as a copy boy in the art department at The New Yorker,[15] a job he held for two years before being fired for angering poet Robert Frost.[16] Years later, he reflected, "Not a very grand job, for all it really involved was sorting cartoons and clipping newspapers. Still, I was fortunate to have it, especially since I was determined never to set a studious foot inside a college classroom. I felt that either one was or wasn't a writer, and no combination of professors could influence the outcome. I still think I was correct, at least in my own case." He left his job to live with relatives in Alabama and began writing his first novel, Summer Crossing.[17]

He was called for induction into the armed services during World War II, but he later told a friend that he was "turned down for everything, including the WACS". He later explained that he was found to be "too neurotic".[2]

Friendship with Harper Lee

[edit]Capote based the character of Idabel in Other Voices, Other Rooms on his Monroeville, Alabama neighbor and best friend, Harper Lee. Capote once acknowledged this: "Mr. and Mrs. Lee, Harper Lee's mother and father, lived very near. She was my best friend. Did you ever read her book, To Kill a Mockingbird? I'm a character in that book, which takes place in the same small town in Alabama where we lived. Her father was a lawyer, and she and I used to go to trials all the time as children. We went to the trials instead of going to the movies."[18] After Lee was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1961 and Capote published In Cold Blood in 1966, the authors became increasingly distant from each other.[19]

Writing career

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

Short story phase

[edit]Capote began writing short stories around the age of eight.[20] In 2013, the Swiss publisher Peter Haag discovered fourteen unpublished stories, written when Capote was a teenager, in the New York Public Library Archives. Random House published these in 2015, under the title The Early Stories of Truman Capote.[21]

Between 1943 and 1946, Capote wrote a continual flow of short fiction, including "Miriam", "My Side of the Matter", and "Shut a Final Door" (for which he won the O. Henry Award in 1948, at the age of 24). His stories were published in both literary quarterlies and well-known popular magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's Bazaar, Harper's Magazine, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Prairie Schooner,[22] and Story. In June 1945, "Miriam" was published by Mademoiselle and went on to win a prize, Best First-Published Story, in 1946. In the spring of 1946, Capote was accepted at Yaddo, the artists and writers colony at Saratoga Springs, New York. (He later endorsed Patricia Highsmith as a Yaddo candidate, and she wrote Strangers on a Train while she was there.)

During an interview for The Paris Review in 1957, Capote said this of his short story technique:

Since each story presents its own technical problems, obviously one can't generalize about them on a two-times-two-equals-four basis. Finding the right form for your story is simply to realize the most natural way of telling the story. The test of whether or not a writer has divined the natural shape of his story is just this: after reading it, can you imagine it differently, or does it silence your imagination and seem to you absolute and final? As an orange is final. As an orange is something nature has made just right.[23]

Random House, the publisher of his novel Other Voices, Other Rooms (see below), moved to capitalize on this novel's success with the publication of A Tree of Night and Other Stories in 1949. In addition to "Miriam", this collection also includes "Shut a Final Door", first published in The Atlantic Monthly (August 1947).

After A Tree of Night, Capote published a collection of his travel writings, Local Color (1950), which included nine essays originally published in magazines between 1946 and 1950.

"A Christmas Memory", a largely autobiographical story taking place in the 1930s, was published in Mademoiselle magazine in 1956. It was issued as a hard-cover standalone edition in 1966, and has since been published in many editions and anthologies.

Posthumously published early novel

[edit]Some time in the 1940s, Capote wrote a novel set in New York City about the summer romance of a socialite and a parking lot attendant.[24] Capote later claimed to have destroyed the manuscript of this novel; but twenty years after his death, in 2004, it came to light that the manuscript had been retrieved from the trash back in 1950 by a house sitter at an apartment formerly occupied by Capote.[25] The novel was published in 2006 by Random House under the title Summer Crossing.

As of 2013, the film rights to Summer Crossing had been purchased by actress Scarlett Johansson, who reportedly planned to direct the adaptation.[26]

First novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms

[edit]The critical success of one of his short stories, "Miriam" (1945), attracted the attention of the publisher Bennett Cerf, resulting in a contract with Random House to write a novel. With an advance of $1,500, Capote returned to Monroeville and began Other Voices, Other Rooms, continuing to work on the manuscript in New Orleans, Saratoga Springs, New York, and North Carolina, eventually completing it in Nantucket, Massachusetts. It was published in 1948. Capote described this symbolic tale as "a poetic explosion in highly suppressed emotion". The novel is a semi-autobiographical refraction of Capote's Alabama childhood. Decades later, writing in The Dogs Bark (1973), he commented:

- Other Voices, Other Rooms was an attempt to exorcise demons, an unconscious, altogether intuitive attempt, for I was not aware, except for a few incidents and descriptions, of its being in any serious degree autobiographical. Rereading it now, I find such self-deception unpardonable.

The story focuses on thirteen-year-old Joel Knox following the loss of his mother. Joel is sent from New Orleans to live with his father, who abandoned him at the time of his birth. Arriving at Skully's Landing, a vast, decaying mansion in rural Alabama, Joel meets his sullen stepmother Amy, debauched transvestite Randolph, and defiant Idabel, a girl who becomes his friend. He also sees a spectral "queer lady" with "fat dribbling curls" watching him from a top window. Despite Joel's queries, the whereabouts of his father remains a mystery. When he finally is allowed to see his father, Joel is stunned to find he is a quadriplegic, having tumbled down a flight of stairs after being inadvertently shot by Randolph. Joel runs away with Idabel but catches pneumonia and eventually returns to the Landing, where he is nursed back to health by Randolph. The implication in the final paragraph is that the "queer lady" beckoning from the window is Randolph in his old Mardi Gras costume. Gerald Clarke, in Capote: A Biography (1988) described the conclusion:

- Finally, when he goes to join the queer lady in the window, Joel accepts his destiny, which is to be homosexual, to always hear other voices and live in other rooms. Yet acceptance is not a surrender; it is a liberation. "I am me", he whoops. "I am Joel, we are the same people." So, in a sense, had Truman rejoiced when he made peace with his own identity.

Harold Halma photograph

[edit]

Other Voices, Other Rooms made The New York Times bestseller list and stayed there for nine weeks, selling more than 26,000 copies. The promotion and controversy surrounding this novel catapulted Capote to fame. A 1947 Harold Halma photograph used to promote the book showed a reclining Capote gazing fiercely into the camera. Gerald Clarke, in Capote: A Biography (1988), wrote, "The famous photograph: Harold Halma's picture on the dustjacket of Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) caused as much comment and controversy as the prose inside. Truman claimed that the camera had caught him off guard, but in fact he had posed himself and was responsible for both the picture and the publicity." Much of the early attention to Capote centered on different interpretations of this photograph, which was viewed as a suggestive pose by some. According to Clarke, the photo created an "uproar" and gave Capote "not only the literary, but also the public personality he had always wanted". The photo made a huge impression on the twenty-year-old Andy Warhol, who often talked about it and wrote fan letters to Capote.[27] When Warhol moved to New York in 1949, he made numerous attempts to meet Capote, and Warhol's fascination with the author led to Warhol's first New York one-man show, Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote at the Hugo Gallery (June 16 – July 3, 1952).[28]

When the photograph was reprinted along with reviews in magazines and newspapers, some readers were amused, but others were outraged and offended. The Los Angeles Times reported that Capote looked "as if he were dreamily contemplating some outrage against conventional morality". The novelist Merle Miller issued a complaint about the photograph at a publishing forum, and it was satirized in the third issue of Mad (making Capote one of the first four celebrities to be spoofed in Mad). The humorist Max Shulman struck an identical pose for the dustjacket photo on his collection, Max Shulman's Large Economy Size (1948). The Broadway stage revue New Faces (and the subsequent film version) featured a skit in which Ronny Graham parodied Capote, deliberately copying his pose in the Halma photograph. Random House featured the Halma photograph in its "This is Truman Capote" ads, and large blowups were displayed in bookstore windows. Walking on Fifth Avenue, Halma overheard two middle-aged women looking at a Capote blowup in the window of a bookstore. When one woman said, "I'm telling you: he's just young", the other woman responded, "And I'm telling you, if he isn't young, he's dangerous!" Capote delighted in retelling this anecdote.

Stage, screen, and magazine work

[edit]In the early 1950s, Capote took on Broadway and films, adapting his 1951 novella, The Grass Harp, into a 1952 play of the same name (later a 1971 musical and a 1995 film), followed by the musical House of Flowers (1954), which spawned the song "A Sleepin' Bee".

In fall of 1952, the same year as his first play, film producer David O. Selznick hired Capote alongside two Hollywood screenwriters for the script of Terminal Station. A few months later in early 1953, John Huston hired him for Beat the Devil.[29] In 1960, while writing In Cold Blood, Jack Clayton approached him to rewrite the script for The Innocents. Capote set aside his novel and in eight weeks produced the script used for the final film.[30]

Traveling through the Soviet Union with a touring production of Porgy and Bess, he produced a series of articles for The New Yorker that became his first book-length work of nonfiction, The Muses Are Heard (1956).

In this period he also wrote an autobiographical essay for Holiday Magazine—one of his personal favorites—about his life in Brooklyn Heights in the late 1950s, titled Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir (1959). In November 2015, The Little Bookroom issued a new coffee-table edition of that work, which includes David Attie's previously-unpublished portraits of Capote as well as Attie's street photography taken in connection with the essay, entitled Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir, With The Lost Photographs of David Attie.[31] This edition was well-reviewed in America and overseas,[32][33] and was also a finalist for a 2016 Indie Book Award.[34]

In 1961 he signed an advertisement for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. He later expressed regret for this, as he had genuinely believed Castro was not a communist.[35]

Breakfast at Tiffany's

[edit]

Breakfast at Tiffany's: A Short Novel and Three Stories (1958) brought together the title novella and three shorter tales: "House of Flowers", "A Diamond Guitar" and "A Christmas Memory". The heroine of Breakfast at Tiffany's, Holly Golightly, became one of Capote's best known creations, and the book's prose style prompted Norman Mailer to call Capote "the most perfect writer of my generation".

The novella itself was originally supposed to be published in Harper's Bazaar's July 1958 issue, several months before its publication in book form by Random House. The publisher of Harper's Bazaar, the Hearst Corporation, began demanding changes to Capote's tart language, which he reluctantly made because he had liked the photos by David Attie and the design work by Harper's art director Alexey Brodovitch that were to accompany the text.[36] But despite his compliance, Hearst ordered Harper's not to run the novella anyway. Its language and subject matter were still deemed "not suitable", and there was concern that Tiffany's, a major advertiser, would react negatively.[37] An outraged Capote resold the novella to Esquire for its November 1958 issue; by his own account, he told Esquire he would only be interested in doing so if Attie's original series of photos was included, but to his disappointment, the magazine ran just a single full-page image of Attie's (another was later used as the cover of at least one paperback edition of the novella).[38] The novella was published by Random House shortly afterwards.

For Capote, Breakfast at Tiffany's was a turning point, as he explained to Roy Newquist (Counterpoint, 1964):

I think I've had two careers. One was the career of precocity, the young person who published a series of books that were really quite remarkable. I can even read them now and evaluate them favorably, as though they were the work of a stranger ... My second career began, I guess it really began with Breakfast at Tiffany's. It involves a different point of view, a different prose style to some degree. Actually, the prose style is an evolvement from one to the other – a pruning and thinning-out to a more subdued, clearer prose. I don't find it as evocative, in many respects, as the other, or even as original, but it is more difficult to do. But I'm nowhere near reaching what I want to do, where I want to go. Presumably this new book is as close as I'm going to get, at least strategically.[39]

In Cold Blood

[edit]The "new book", In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences (1965), was inspired by a 300-word article that ran in the November 16, 1959, issue of The New York Times. The story described the unexplained murder of the Clutter family in rural Holcomb, Kansas, and quoted the local sheriff as saying, "This is apparently the case of a psychopathic killer."[40] Fascinated by this brief news item, Capote traveled with Harper Lee to Holcomb and visited the scene of the massacre. Over the course of the next few years, he became acquainted with everyone involved in the investigation and most of the residents of the small town and the area. Rather than taking notes during interviews, Capote committed conversations to memory and immediately wrote quotes as soon as an interview ended. He claimed his memory retention for verbatim conversations had been tested at "over 90%".[41] Lee made inroads into the community by befriending the wives of those Capote wanted to interview.

Capote recalled his years in Kansas when he spoke at the 1974 San Francisco International Film Festival:

I spent four years on and off in that part of Western Kansas there during the research for that book and then the film. What was it like? It was very lonely. And difficult. Although I made a lot of friends there. I had to, otherwise I never could have researched the book properly. The reason was I wanted to make an experiment in journalistic writing, and I was looking for a subject that would have sufficient proportions. I'd already done a great deal of narrative journalistic writing in this experimental vein in the 1950s for The New Yorker ... But I was looking for something very special that would give me a lot of scope. I had come up with two or three different subjects and each of them for whatever reasons was a dry run after I'd done a lot of work on them. And one day I was gleaning The New York Times, and way on the back page I saw this very small item. And it just said, "Kansas Farmer Slain. Family of Four is Slain in Kansas". A little item just about like that. And the community was completely nonplussed, and it was this total mystery of how it could have been, and what happened. And I don't know what it was. I think it was that I knew nothing about Kansas or that part of the country or anything. And I thought, "Well, that will be a fresh perspective for me" ... And I said, "Well, I'm just going to go out there and just look around and see what this is." And so maybe this is the subject I've been looking for. Maybe a crime of this kind is ... in a small town. It has no publicity around it and yet had some strange ordinariness about it. So I went out there, and I arrived just two days after the Clutters' funeral. The whole thing was a complete mystery and was for two and a half months. Nothing happened. I stayed there and kept researching it and researching it and got very friendly with the various authorities and the detectives on the case. But I never knew whether it was going to be interesting or not. You know, I mean anything could have happened. They could have never caught the killers. Or if they had caught the killers ... it may have turned out to be something completely uninteresting to me. Or maybe they would never have spoken to me or wanted to cooperate with me. But as it so happened, they did catch them. In January, the case was solved, and then I made very close contact with these two boys and saw them very often over the next four years until they were executed. But I never knew ... when I was even halfway through the book, when I had been working on it for a year and a half, I didn't honestly know whether I would go on with it or not, whether it would finally evolve itself into something that would be worth all that effort. Because it was a tremendous effort.[42]

In Cold Blood was published in 1966 by Random House after having been serialized in The New Yorker. The "nonfiction novel", as Capote labeled it, brought him literary acclaim and became an international bestseller, but Capote would never complete another novel after it.

A feud between Capote and British arts critic Kenneth Tynan erupted in the pages of The Observer after Tynan's review of In Cold Blood implied that Capote wanted an execution so the book would have an effective ending. Tynan wrote:

We are talking, in the long run, about responsibility; the debt that a writer arguably owes to those who provide him – down to the last autobiographical parentheses – with his subject matter and his livelihood ... For the first time an influential writer of the front rank has been placed in a position of privileged intimacy with criminals about to die, and – in my view – done less than he might have to save them. The focus narrows sharply down on priorities: Does the work come first, or does life? An attempt to help (by supplying new psychiatric testimony) might easily have failed: what one misses is any sign that it was ever contemplated.[43]

Veracity of In Cold Blood and other nonfiction

[edit]In Cold Blood brought Capote much praise from the literary community, but there were some who questioned certain events as reported in the book. Writing in Esquire in 1966, Phillip K. Tompkins noted factual discrepancies after he traveled to Kansas and spoke to some of the same people interviewed by Capote. In a telephone interview with Tompkins, Mrs. Meier denied that she heard Perry cry and that she held his hand as described by Capote. In Cold Blood indicates that Meier and Perry became close, yet she told Tompkins she spent little time with Perry and did not talk much with him. Tompkins concluded:

Capote has, in short, achieved a work of art. He has told exceedingly well a tale of high terror in his own way. But, despite the brilliance of his self-publicizing efforts, he has made both a tactical and a moral error that will hurt him in the short run. By insisting that "every word" of his book is true he has made himself vulnerable to those readers who are prepared to examine seriously such a sweeping claim.

True crime writer Jack Olsen also commented on the fabrications:

I recognized it as a work of art, but I know fakery when I see it," Olsen says. "Capote completely fabricated quotes and whole scenes ... The book made something like $6 million in 1960s money, and nobody wanted to discuss anything wrong with a moneymaker like that in the publishing business." Nobody except Olsen and a few others. His criticisms were quoted in Esquire, to which Capote replied, "Jack Olsen is just jealous." "That was true, of course," Olsen says, "I was jealous – all that money? I'd been assigned the Clutter case by Harper & Row until we found out that Capote and his cousin [sic], Harper Lee, had been already on the case in Dodge City for six months." Olsen explains, "That book did two things. It made true crime an interesting, successful, commercial genre, but it also began the process of tearing it down. I blew the whistle in my own weak way. I'd only published a couple of books at that time – but since it was such a superbly written book, nobody wanted to hear about it.[44]

Alvin Dewey, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation detective portrayed in In Cold Blood, later said that the last scene, in which he visits the Clutters' graves, was Capote's invention, while other Kansas residents whom Capote interviewed have claimed they or their relatives were mischaracterized or misquoted.[45] Dewey and his wife Marie became friends of Capote during the time Capote spent in Kansas gathering research for his book.[46] Dewey gave Capote access to the case files and other items related to the investigation and to the members of the Clutter family, including Nancy Clutter's diary.[46] When the film version of the book was made in 1967, Capote arranged for Marie Dewey to receive $10,000 from Columbia Pictures as a paid consultant to the making of the film.[46]

Another work described by Capote as "nonfiction" was later reported to have been largely fabricated. In a 1992 piece in the Sunday Times, reporters Peter and Leni Gillman investigated the source of "Handcarved Coffins", the story in Capote's last work Music for Chameleons subtitled "a nonfiction account of an American crime". They found no reported series of American murders in the same town that included all of the details Capote described – the sending of miniature coffins, a rattlesnake murder, a decapitation, etc. Instead, they found that a few of the details closely mirrored an unsolved case on which investigator Al Dewey had worked. Their conclusion was that Capote had invented the rest of the story, including his meetings with the suspected killer, Quinn.[47]

Years following In Cold Blood

[edit]Now more sought after than ever, Capote wrote occasional brief articles for magazines, and also entrenched himself more deeply in the world of the jet set. Gore Vidal once observed, "Truman Capote has tried, with some success, to get into a world that I have tried, with some success, to get out of."[48]

In the late 1960s, he became friendly with Lee Radziwill, the sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Radziwill was an aspiring actress and had been panned for her performance in a production of The Philadelphia Story in Chicago. Capote was commissioned to write the teleplay for a 1967 television production starring Radziwill: an adaptation of the classic Otto Preminger film Laura (1944). The adaptation, and Radziwill's performance in particular, received indifferent reviews and poor ratings; arguably, it was Capote's first major professional setback. Radziwill supplanted the older Babe Paley as Capote's primary female companion in public throughout the better part of the 1970s.

On November 28, 1966, in honor of The Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham, Capote hosted a now-legendary masked ball, called the Black and White Ball, in the Grand Ballroom of New York City's Plaza Hotel. It was considered the social event of not only that season but of many to follow, with The New York Times and other publications giving it considerable coverage. Capote dangled the prized invitations for months, snubbing early supporters like fellow Southern writer Carson McCullers as he determined who was "in" and who was "out".[49]

Despite the assertion earlier in life that one "lost an IQ point for every year spent on the West Coast", he purchased a home in Palm Springs and began to indulge in a more aimless life and heavy drinking. This resulted in bitter quarreling with Jack Dunphy, with whom he had shared a nonexclusive relationship since the 1950s. Their partnership changed form and continued as a nonsexual one, and they were separated during much of the 1970s.

Capote never finished another novel after In Cold Blood. The dearth of new prose and other failures, including a rejected screenplay for Paramount Pictures's 1974 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, were counteracted by Capote's frequenting of the talk show circuit. In 1972, Capote accompanied The Rolling Stones on their first American tour since 1969 as a correspondent for Rolling Stone. He ultimately refused to write the article, so the magazine recouped its interests by publishing in April 1973 an interview of the author conducted by Andy Warhol. A collection of previously published essays and reportage, The Dogs Bark: Public People and Private Places, appeared later that year.

In July 1973, Capote met John O'Shea, the middle-aged vice president of a Marine Midland Bank branch on Long Island, while visiting a New York bathhouse. The married father of three did not identify as homosexual or bisexual, perceiving his visits as being a "kind of masturbation".[50] However, O'Shea found Capote's fortune alluring and harbored aspirations to become a professional writer. After consummating their relationship in Palm Springs, the two engaged in a war of jealousy and manipulation for the remainder of the decade. Longtime friends were appalled when O'Shea, who was officially employed as Capote's manager, attempted to take control of the author's literary and business interests.

Answered Prayers

[edit]Through his jet set social life Capote had been gathering observations for a tell-all novel, eventually to be published as Answered Prayers. The book, which had been in the planning stages since 1958, was intended to be the American equivalent of Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time and a culmination of the "nonfiction novel" format. Initially scheduled for publication in 1968, the novel was eventually delayed, at Capote's insistence, to 1972. Because of the delay, he was forced to return money received for the film rights to 20th Century Fox. Capote spoke about the novel in interviews, but continued to postpone his manuscript's delivery date.

Capote permitted Esquire to publish four chapters of the unfinished novel in 1975 and 1976. The first to appear, "Mojave", ran as a self-contained short story and was favorably received, but the second, "La Côte Basque 1965", based in part on the dysfunctional personal lives of Capote's friends William S. Paley and Babe Paley, generated controversy. The issue featuring "La Côte Basque" sold out immediately upon publication; its much-discussed betrayal of confidences alienated Capote from his established base of middle-aged, wealthy female friends, who feared the intimate and often sordid details of their ostensibly glamorous lives would be exposed to the public. Another two chapters – "Unspoiled Monsters" and "Kate McCloud" – appeared subsequently. These texts were intended to form the long opening section of the novel. They displayed a marked shift in narrative voice, introduced a more elaborate plot structure, and together formed a novella-length mosaic of fictionalized memoir and gossip. "Unspoiled Monsters", which by itself was almost as long as Breakfast at Tiffany's, contained a thinly veiled satire of Tennessee Williams, whose friendship with Capote had become strained.

As much as Capote had completed of the novel was published after his death as Answered Prayers: The Unfinished Novel in 1986 in the UK and in the US in 1987. It comprised "Unspoiled Monsters", "Kate McCloud", and "La Cote Basque 1965", but not "Mojave", which Capote had "removed from the novel's master plan" and instead published in the collection Music for Chameleons in 1980.[51]

"La Côte Basque 1965"

[edit]"La Côte Basque 1965" was published as a standalone chapter in Esquire magazine in November 1975. The catty beginning to his still-unfinished novel, Answered Prayers, was the catalyst of Capote's social suicide. Many of Capote's circle of high-society female friends, whom he called his "swans", were featured in the text, some under pseudonyms and others by their real names. The chapter is said to have revealed the dirty secrets of these women,[52] and aired the "dirty laundry" of New York City's elite. As a result Capote was ostracized from New York society and from many of his former friends.[53]

"La Côte Basque" begins as Jonesy, the main character, said to be based on a mixture of Capote himself and Herbert Clutter,[54] the serial killer victim at the center of In Cold Blood, has a rendezvous with Lady Ina Coolbirth on a New York City street. Described as "an American married to a British chemicals tycoon and a lot of woman in every way",[55] she is widely rumoured to be based on New York socialite Slim Keith. Coolbirth invites Jonesy to lunch at La Côte Basque. A gossipy tale of New York's elite ensues.

The characters of Gloria Vanderbilt and Carol Matthau are encountered first, the two women gossiping about Princess Margaret, Prince Charles and the rest of the British royal family. An awkward moment occurs when Vanderbilt has a run-in with her first husband and fails to recognize him. It is only at Mrs. Matthau's prompting that Vanderbilt realizes who he is. Both women brush the incident aside and chalk it up to ancient history.

The characters of Lee Radziwill and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis are then encountered when they enter the restaurant together. Sisters, they draw the attention of the room although they speak only to each other. Coolbirth describes Lee as "marvelously made, like a Tanagra figurine" and Jacqueline as "photogenic" yet "unrefined, exaggerated".[56]

The character of Ann Hopkins is then introduced when she surreptitiously walks into the restaurant and sits down with a pastor. Hopkins is likened to Ann Woodward. Coolbirth relates the story of how Hopkins murdered her husband. When he threatened to divorce her, she began cultivating a rumour that a burglar was harassing their neighbourhood. The official police report says that while she and her husband were sleeping in separate bedrooms, Mrs. Hopkins heard someone enter her bedroom. In her panic, she grabbed her gun and shot the intruder; unbeknownst to her the intruder was in fact her husband, David Hopkins (or William Woodward, Jr.). Ina Coolbirth suggests however, that Mr. Hopkins was in fact shot in the shower; such is the wealth and power of the Hopkins' family that any charges or whispers of murder simply floated away at the inquest. It is rumoured that Ann Woodward was warned prematurely of the publication and content of Capote's "La Côte Basque" and proceeded to kill herself with cyanide as a result.[52]

An incident regarding the character of Sidney Dillon (or William S. Paley) is then discussed between Jonesy and Mrs. Coolbirth. Sidney Dillon is said to have told Ina Coolbirth this story because they have a history as former lovers. One evening while Cleo Dillon (Babe Paley) was out of the city, in Boston, Sidney Dillon attended an event by himself at which he was seated next to the wife of a prominent New York Governor. The two began to flirt and eventually went home together. While Ina suggests that Sidney Dillon loves his wife, it is his inexhaustible need for acceptance by haute New York society that motivates him to be unfaithful. Sidney Dillon and the woman sleep together, and afterwards Mr. Dillon discovers a very large blood stain on the sheets, which represents her mockery of him. Mr. Dillon then spends the rest of the night and early morning washing the sheet by hand, with scalding water in an attempt to conceal his unfaithfulness from his wife who is due to arrive home the same morning. In the end, Dillon falls asleep on a damp sheet and wakes up to a note from his wife telling him she had arrived while he was sleeping, did not want to wake him, and that she would see him at home.

The aftermath of the publication of "La Côte Basque" is said to have pushed Truman Capote to new levels of drug abuse and alcoholism, mainly because he claimed not to have anticipated the backlash it would cause in his personal life.

Last years

[edit]Capote was in and out of drug rehabilitation clinics in the late 1970s, and news of his various breakdowns frequently reached the public.[57] During a 1978 on-air interview with Stanley Siegel, an extraordinarily intoxicated Capote confessed he had been awake for 48 hours, and when Siegel asked "What's going to happen unless you lick this problem of drugs and alcohol?" Capote responded, "The obvious answer is that eventually, I mean, I'll kill myself...without meaning to."[58] The live broadcast made national headlines. One year later, feeling betrayed by Lee Radziwill in a feud with perpetual nemesis Gore Vidal, Capote arranged a return visit to Stanley Siegel's show, delivering a bizarrely comic performance revealing an incident wherein Vidal was thrown out of the Kennedy White House due to intoxication (later refuted in detail by Vidal in his memoir Palimpsest). Capote also shared salacious details regarding the personal life of Radziwill and her sister, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Capote and Andy Warhol had mutual admiration for each other. Warhol had looked up to the writer as a mentor in his early days in New York and Capote also claimed an admiration for Warhol's The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B & Back Again. They often partied together New York's Studio 54, and Warhol agreed to paint Capote's portrait as "a personal gift" in exchange for Capote's contributing short pieces to Warhol's Interview magazine every month for a year in the form of a column, Conversations with Capote. Initially the pieces were to consist of tape-recorded conversations, but soon Capote eschewed the tape recorder in favor of semi-fictionalized "conversational portraits". These pieces formed the basis for the bestselling Music for Chameleons (1980).

Capote underwent a facelift, lost weight, and experimented with hair transplants.[59] Despite this, Capote was unable to overcome his reliance upon drugs and liquor and had grown bored with New York by the beginning of the 1980s.

After the revocation of his driver's license (the result of speeding near his Long Island residence) and a hallucination-based seizure in 1980 that required hospitalization, Capote became fairly reclusive. These hallucinations continued unabated; medical scans eventually revealed that his brain mass had perceptibly shrunk. On the rare occasions when he was lucid, he continued to promote Answered Prayers as being nearly complete and was reportedly planning a reprise of the Black and White Ball to be held either in Los Angeles or a more exotic locale in South America. On a few occasions, he was still able to write. In 1982, a new short story, "One Christmas", appeared in the December issue of Ladies' Home Journal; the following year it became, like its predecessors A Christmas Memory and The Thanksgiving Visitor, a holiday gift book. In 1983, "Remembering Tennessee", an essay in tribute to Tennessee Williams, who had died in February of that year, appeared in Playboy magazine.[60]

Death

[edit]

Capote died in Bel Air, Los Angeles, on August 25, 1984.[61] According to the coroner's report, the cause of death was "liver disease complicated by phlebitis and multiple drug intoxication".[62] He died at the home of his old friend Joanne Carson, ex-wife of late-night TV host Johnny Carson, on whose program Capote was a frequent guest. Gore Vidal responded to news of Capote's death by calling it "a wise career move".[63]

Capote was cremated and his remains were reportedly divided between Carson and Jack Dunphy (although Dunphy maintained that he received all the ashes).[64] Carson said she kept the ashes in an urn in the room where he died. The ashes were reported stolen during a Halloween party in 1988 along with $200,000 in jewels but were then returned six days later, having been found in a coiled-up garden hose on the back steps of Carson's Bel Air home.[64] The ashes were reportedly stolen again when taken to a production of Tru, but the thief was caught before leaving the theatre. Carson bought a crypt at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles.[64] Dunphy died in 1992, and in 1994, both his and Capote's ashes were reportedly scattered at Crooked Pond, between Bridgehampton, New York, and Sag Harbor, New York on Long Island, close to Sagaponack, New York, where the two had maintained a property with individual houses for many years. Crooked Pond was chosen because money from the estate of Dunphy and Capote was donated to the Nature Conservancy, which in turn used it to buy 20 acres around Crooked Pond in an area called "Long Pond Greenbelt". A stone marker indicates the spot where their mingled ashes were thrown into the pond.[65] In 2016, some of Capote's ashes previously owned by Joanne Carson were auctioned by Julien's Auctions.[66]

Capote also maintained the property in Palm Springs,[67] a condominium in Switzerland that was mostly occupied by Dunphy seasonally, and a primary residence at 860 United Nations Plaza in New York City. Capote's will provided that after Dunphy's death, a literary trust would be established, sustained by revenues from Capote's works, to fund various literary prizes, fellowships and scholarships, including the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism in Memory of Newton Arvin, commemorating not only Capote but also his friend Newton Arvin, the Smith College professor and critic who lost his job after his homosexuality was revealed.[68] As such, the Truman Capote Literary Trust was established in 1994, two years after Dunphy's death.

Personal life

[edit]Sexuality

[edit]Capote was openly gay. Although Capote never embraced the Gay Rights Movement, his own openness about homosexuality and his encouragement for openness in others made him an important player in the realm of gay rights.[69] In his piece "Capote and the Trillings: Homophobia and Literary Culture at Midcentury", Jeff Solomon details an encounter between Capote and Lionel and Diana Trilling – two New York intellectuals and literary critics – in which Capote questioned the motives of Lionel, who had recently published a book on E. M. Forster but had ignored the author's homosexuality. Solomon argues:

When Capote confronts the Trillings on the train, he attacks their identity as literary and social critics committed to literature as a tool for social justice, capable of questioning both their own and their society's preconceptions, and sensitive to prejudice by virtue of their heritage and, in Diana's case, by her gender.[70]

Relationships

[edit]One of his first serious lovers was Smith College literature professor Newton Arvin, who won the National Book Award for his Herman Melville biography in 1951 and to whom Capote dedicated Other Voices, Other Rooms.[71][72]

Capote spent three decades partnered with Jack Dunphy, a fellow writer. In his book, "Dear Genius ..." A Memoir of My Life with Truman Capote, Dunphy attempts both to explain the Capote he knew and loved within their relationship and the very success-driven and, eventually, drug- and alcohol-addicted person who existed outside of their relationship.[73] Their separate living quarters allowed autonomy within the relationship and, as Dunphy admitted, "spared [him] the anguish of watching Capote drink and take drugs".[74] Their relationship ultimately became platonic after Truman’s story "La Côte Basque, 1965" was published in Esquire in 1975, but their lives remained intertwined.[75] Dunphy was named the chief beneficiary in Capote's will.[75]

In 1973, Capote met John O'Shea, a married banker from Long Island, who became his business manager and lover.[75] They had a toxic relationship as both men were heavy drinkers. Reportedly, O'Shea would become verbally and emotionally abusive when intoxicated.[76]

Capote was often seen with his companion Bob MacBride, a computer engineer for IBM and sculptor.[77][78] In the book The Andy Warhol Diaries, Capote's friend Andy Warhol referred to MacBride as Capote's boyfriend and mentioned that MacBride had left his wife and children in a June 29, 1978, diary entry.[79] Their relationship was a "bond of brothers rather than of lovers" according to MacBride.[79][80] They met at a bookstore in 1972, but Capote distanced himself from MacBride after he met O'Shea.[79] Capote rekindled his relationship with MacBride in 1978.[80]

Public persona

[edit]Capote was well known for his distinctive, high-pitched voice and odd vocal mannerisms, his offbeat manner of dress, and his fabrications. He often claimed to know intimately people whom he had in fact never met, such as Greta Garbo.[citation needed] He professed to have had numerous liaisons with men thought to be heterosexual, including, he claimed, Errol Flynn. He traveled in an eclectic array of social circles, hobnobbing with authors, critics, business tycoons, philanthropists, Hollywood and theatrical celebrities, royalty, and members of high society, both in the U.S. and abroad. Part of his public persona was a longstanding rivalry with writer Gore Vidal. Their rivalry prompted Tennessee Williams to complain: "You would think they were running neck-and-neck for some fabulous gold prize." Apart from his favorite authors (Willa Cather, Isak Dinesen, and Marcel Proust), Capote had faint praise for other writers. However, one who did receive his favorable endorsement was journalist Lacey Fosburgh, author of Closing Time: The True Story of the Goodbar Murder (1977).

Legacy

[edit]Capote's childhood is the focus of a permanent exhibit in Monroeville, Alabama's Old Courthouse Museum, covering his life in Monroeville with his Faulk cousins and how those early years are reflected in his writing.[81] The exhibit brings together photos, letters and memorabilia to paint a portrait of Capote's early life in Monroeville. Jennings Faulk Carter donated the collection to the Museum in 2005. The collection comprises 12 handwritten letters (1940s–60s) from Capote to his favorite aunt, Mary Ida Carter (Jennings' mother). Many of the items in the collection belonged to his mother and Virginia Hurd Faulk, Carter's cousin with whom Capote lived as a child.

The exhibit features many references to Sook, but two items in particular are always favorites of visitors: Sook's "Coat of Many Colors" and Truman's baby blanket. Truman's first cousin recalls that as children, he and Truman never had trouble finding Sook in the darkened house on South Alabama Avenue because they simply looked for the bright colors of her coat. Truman's baby blanket is a "granny square" blanket Sook made for him. The blanket became one of Truman's most cherished possessions, and friends say he was seldom without it – even when traveling. In fact, he took the blanket with him when he flew from New York to Los Angeles to be with Joanne Carson on August 23, 1984. According to Joanne Carson, when he died at her home on August 25, his last words were, "It's me, it's Buddy," followed by, "I'm cold." Buddy was Sook's name for him.

Capote on film

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

- In 1961, Capote's novel Breakfast at Tiffany's (1958), about a flamboyant New York party girl named Holly Golightly, was filmed by director Blake Edwards and starred Audrey Hepburn in what many consider her defining role, though Capote never approved of the many changes to the story, made to appeal to mass audiences.

- Capote's childhood experiences are captured in the memoir A Christmas Memory (1956), which he adapted for television and narrated. Directed by Frank Perry, it aired on December 21, 1966, on ABC Stage 67, and featured Geraldine Page in an Emmy Award-winning performance.

- When Richard Brooks directed In Cold Blood, the 1967 adaptation of the novel, with Robert Blake and Scott Wilson, he filmed at the actual Clutter house and other Holcomb, Kansas, locations.

- Capote narrated his The Thanksgiving Visitor (1967), a sequel to A Christmas Memory, filmed by Frank Perry in Pike Road, Alabama. Geraldine Page again won an Emmy for her performance in this hour-long teleplay.

- The ABC Stage 67 teleplay was later incorporated into Perry's 1969 anthology film Trilogy (aka Truman Capote's Trilogy), which also includes adaptations of "Miriam" and "Among the Paths to Eden".

- Neil Simon's murder mystery spoof Murder by Death (1976) provided Capote's main role as an actor, portraying reclusive millionaire Lionel Twain who invites the world's leading detectives together to a dinner party to have them solve a murder. The performance brought him a Golden Globe Award nomination (Best Acting Debut in a Motion Picture). Early in the film, it is alleged that Twain has ten fingers but no pinkies. In truth, Capote's pinkie fingers were unusually large. In the film, Capote's character is highly critical of detective fiction from the likes of Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammett.

- Woody Allen's Annie Hall (1977) includes a scene in which Alvy (Allen) and Annie (Diane Keaton) are observing passersby in the park. Alvy comments, "Oh, there's the winner of the Truman Capote Look-Alike Contest". The passerby is actually Truman Capote (who appeared in the film uncredited).

- Other Voices, Other Rooms (1995) stars David Speck in the lead role of Joel Sansom. Reviewing this atmospheric Southern Gothic film in The New York Times, Stephen Holden wrote:

One of the things the movie does best is transport you back in time and into nature. In the early scenes as Joel leaves his aunt's home to travel across the South by rickety bus and horse and carriage, you feel the strangeness, wonder and anxiety of a child abandoning everything that's familiar to go to a place so remote he has to ask directions along the way. The landscape over which he travels is so rich and fertile that you can almost smell the earth and sky. Later on, when Joel tussles with Idabel (Aubrey Dollar), a tomboyish neighbor who becomes his best friend (a character inspired by the author Harper Lee), the movie has a special force and clarity in its evocation of the physical immediacy of being a child playing outdoors.[82]

- In 1995, Capote's novella The Grass Harp (1951), which he later turned into a 1952 play, was made into a film version with a screenplay by Stirling Silliphant and directed by Charles Matthau, Walter Matthau's son. This story is somewhat autobiographical of Capote's childhood in Alabama.[83]

- Anthony Edwards and Eric Roberts headed the cast of the 1996 In Cold Blood miniseries, directed by Jonathan Kaplan.

- The TV movie Truman Capote's A Christmas Memory (1997), with Patty Duke and Piper Laurie, was a remake of the 1966 television show, directed by Glenn Jordan.

- In 2002, director Mark Medoff brought to film Capote's short story "Children on Their Birthdays", another look back at a small-town Alabama childhood.

Documentaries

[edit]- With Love from Truman (1966), a 29-minute documentary by David and Albert Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, shows a Newsweek reporter interviewing Capote at his beachfront home in Long Island. Capote talks about In Cold Blood, his relationship with the murderers, and his coverage of the trial. He is also seen taking Alvin Dewey and his wife around New York City for the first time. Originally titled A Visit with Truman Capote, this film was commissioned by National Educational Television and shown on the NET network.[84]

- Truman Capote: The Tiny Terror (original airdate December 17, 1997) is a documentary that aired as part of A&E's Biography series,[85] followed by a 2005 DVD release.[86]

- The Capote Tapes (2019), directed by Ebs Burnough. Using "never-before-heard" audio archives and interviews with Capote and his associates, the film centers around Capote's unfinished novel, Answered Prayers.[87]

Portrayals of Capote

[edit]Theatre

[edit]- In 1990, Robert Morse received both a Tony[88] and a Drama Desk Award for his portrayal of Capote in the one-man show Tru.

- In 1994, actor-writer Bob Kingdom created the one-man theatre piece The Truman Capote Talk Show, in which he played Capote looking back over his life. Originally performed at the Lyric Studio Theatre, Hammersmith, London, the show has toured widely within the UK and internationally.[citation needed]

- In 1996, Louis Negin appeared in a Toronto production of Tru.[89]

- In 2022, The Wind Is Us: The Death that Killed Capote, a play by Mike Broemmel and starring Eddie Schumacher, went into production.[90]

Film

[edit]- In 54 (1998), with Louis Negin in the role of Capote, a reference is made to Capote just having had a face lift, and the song "Knock on Wood" is dedicated to him.[citation needed]

- In Isn't She Great (2000), Sam Street is seen briefly as Capote. The film is a biographical comedy-drama about Jacqueline Susann.[91]

- In The Audrey Hepburn Story (2000), Michael J. Burg played Capote; and again in The Hoax (2006) (in deleted scenes).[92]

- In Capote (2005), Capote was played by Philip Seymour Hoffman with Catherine Keener as Harper Lee. The biographical film is the dramatic feature debut of director Bennett Miller. Spanning the years Capote spent researching and writing In Cold Blood, the film depicts Capote's conflict between his compassion for his subjects and self-absorbed obsession with finishing the book. Capote garnered much critical acclaim when it was released (September 30, 2005, in the US and February 24, 2006, in the UK). Dan Futterman's screenplay was based on the book Capote: A Biography by Gerald Clarke (1988).[citation needed] Capote received five Academy Award nominations: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress. Hoffman's performance earned him many awards, including an Oscar for Best Actor in a Leading Role, a BAFTA Award, a Golden Globe Award, a Screen Actors Guild Award, and an Independent Spirit Award.

- Infamous (2006), directed by Douglas McGrath and starring Toby Jones as Capote and Sandra Bullock as Harper Lee, is an adaptation of George Plimpton's Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career (1997). On the DVD commentary track, McGrath admits to the occasional scene being compiled and drawn together by using the truth and blended with his own "imagination" of how the actual story evolved.[citation needed]

Television

[edit]- In 1992, Robert Morse recreated his role as Capote in the play Tru for the PBS series American Playhouse and won an Emmy Award for his performance.[93]

- Michael J. Burg appeared as Capote in an episode of ABC-TV's short-lived series Life on Mars (2009).[92]

- Tom Hollander portrays Capote in Capote vs. The Swans (2024), the second season of the anthology series Feud,[94] based on Laurence Leamer's book Capote's Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal and a Swan Song for an Era, and received a Primetime Emmy Award nomination for his portrayal.[95]

Literature

[edit]- The Swans of Fifth Avenue: A Novel (2016) by Melanie Benjamin tells the story of the evolution of Capote's friendship with Babe Paley and the New York "swans", and his fallout from high society after the publication of "La Côte Basque 1965".[96][97]

Discography

[edit]- House of Flowers (1954) Columbia 2320. (LP) Broadway production. Saint Subber presents Truman Capote and Harold Arlen's House of Flowers, starring Pearl Bailey. Directed by Peter Brook with musical numbers by Herbert Ross. Columbia 12" LP, Stereo-OS-2320. Electronically reprocessed for stereo.

- Children on Their Birthdays (1955) Columbia Literary Series ML 4761 12" LP. Reading by Capote.

- House of Flowers (1955) Columbia Masterworks 12508. (LP) Read by the Author.

- A Christmas Memory (1959) United Artists UAL 9001. (LP) Truman Capote reading his A Christmas Memory.

- In Cold Blood (1966) RCA Victor Red Seal monophonic VDM-110. (LP) Truman Capote reads scenes from In Cold Blood.

- The Thanksgiving Visitor (1967) United Artists UAS 6682. (LP) Truman Capote reading his The Thanksgiving Visitor.

- Capote (2006) RCA, Film Soundtrack. Includes complete 1966 RCA recording Truman Capote reads scenes from In Cold Blood

- In Cold Blood (2006) Random House unabridged on 12 CDs. Read by Scott Brick.

Works

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1945 | "Miriam" | Short story; published in Mademoiselle |

| 1948 | Other Voices, Other Rooms | Novel |

| 1949 | A Tree of Night and Other Stories | Collection of short stories |

| 1950 | "House of Flowers" | Short story; the first chapter was published in Botteghe Oscure in 1950 and in Harper's Bazaar in 1951 |

| 1950 | Local Color | Book; collection of European travel essays |

| 1951 | The Grass Harp | Novel |

| 1952 | The Grass Harp | Play |

| 1953 | Beat the Devil | Original screenplay |

| Terminal Station | Screenplay (dialogue only) | |

| 1954 | House of Flowers | Broadway musical |

| 1955 | "Carmen Therezinha Solbiati – So Chic" | Short story (Brazilian jet-setter Carmen Mayrink Veiga); published in Vogue in 1956[citation needed] |

| 1956 | The Muses Are Heard | Nonfiction |

| 1956 | "A Christmas Memory" | Short story; published in Mademoiselle |

| 1957 | "The Duke in His Domain" | Profile of Marlon Brando; published in The New Yorker; Republished in Life Stories: Profiles from The New Yorker in 2001 |

| 1958 | Breakfast at Tiffany's | Novella |

| 1959 | "Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir" | Autobiographical essay, photos by David Attie; published in the February 1959 issue of Holiday Magazine and later as "A House On The Heights" in 2002 (see below) |

| 1959 | Observations | Collaborative art and photography book; photos by Richard Avedon, comments by Truman Capote and design by Alexey Brodovitch |

| 1960 | The Innocents | Screenplay based on The Turn of the Screw by Henry James; 1962 Edgar Award, from the Mystery Writers of America, to Capote and William Archibald for Best Motion Picture Screenplay |

| 1963 | Selected Writings of Truman Capote | Midcareer retrospective anthology; fiction and nonfiction |

| 1964 | A short story appeared in Seventeen magazine | |

| 1965 | In Cold Blood | "Nonfiction novel"; Capote's second Edgar Award (1966), for Best Fact Crime book |

| 1967 | "A Christmas Memory" | Best Screenplay Emmy Award; ABC TV movie |

| 1968 | The Thanksgiving Visitor | Short story published as a gift book |

| Laura | Television film; original screenplay | |

| 1973 | The Dogs Bark | Collection of travel articles and personal sketches |

| 1975 | "Mojave" and "La Cote Basque, 1965" | Short stories published in Esquire |

| 1976 | "Unspoiled Monsters" and "Kate McCloud" | Short stories published in Esquire |

| 1980 | Music for Chameleons | Collection of short works mixing fiction and nonfiction |

| 1983 | "One Christmas" | Short story published as a gift book |

| 1986 | Answered Prayers: The Unfinished Novel | Published posthumously, in the UK in 1986, in the US in 1987. |

| 1987 | A Capote Reader | Omnibus edition containing most of Capote's shorter works, fiction and nonfiction |

| 2002 | A House on the Heights | Book edition of Capote's essay, "Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir (1959), with a new introduction by George Plimpton |

| 2004 | The Complete Stories of Truman Capote | Anthology of twenty short stories |

| 2004 | Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote | Edited by Capote biographer Gerald Clarke |

| 2006 | Summer Crossing | Novel; Published by Random House |

| 2007 | Portraits and Observations: The Essays of Truman Capote | Published by Random House |

| 2015 | The Early Stories of Truman Capote | Published by Random House; 14 previously unpublished stories, written by Capote when he was a teenager, discovered in the New York Public Library Archives in 2013. |

| 2023 | "Another Day in Paradise" | Published in The Strand magazine; discovered in the archives of the Library of Congress,[76] written in Sicily in the 1950s |

References

[edit]- ^ "Truman Capote: Early Life". Biography.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c Clarke, Gerald (2005). Capote: a biography (2nd Carroll & Graf ed.). New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 9780786716616.

- ^ Fakazis, Liz. "New Journalism". Britannica. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ The Dick Cavett Show, aired August 21, 1980

- ^ Barra, Allen Archived February 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine "Screenings: The Triumph of Capote," American Heritage, June/July 2006.

- ^ Minzesheimer, Bob (December 17, 2007). "'Kansas' imagines Truman Capote-Harper Lee rift". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Capote, Truman; M. Thomas Inge (1987). Truman Capote: conversations. University Press of Mississippi. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-87805-275-2. Archived from the original on January 19, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ Shields, Charles J. (2006). Mockingbird: a portrait of Harper Lee. Macmillan. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8050-7919-7. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ "Truman Capote is Dead at 59; Novelist of Style and Clarity". The New York Times. August 26, 1984. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Inge, M. Thomas, ed. (1987). Truman Capote Conversations: Pati Hill interview from Paris Review 16 (1957). University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9780878052752. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ Walter, Eugene, as told to Katherine Clark. (2001). Milking the Moon: A Southerner's Story of Life on This Planet. Crown.

- ^ "Alumni". The Scholastic Arts & Writing Awards. Archived from the original on October 5, 2009.

- ^ "El escritor Truman Capote y su vínculo adoptivo con el municipio de El Paso | Diario de Avisos". Diario de Avisos (in European Spanish). October 19, 2016. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Oakes, Elizabeth (2004). American Writers. Facts On File, Inc. p. 69. ISBN 9781438108094.

- ^ a b Clarke, Gerald (2005). Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote. Random House. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-375-70241-9.

- ^ Shuman, R. Baird, ed. (2002). Great American Writers: Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 233–254.

- ^ Long, Robert Emmet (2000). "Truman Capote". Critical Survey of Long Fiction (Second Revised ed.). Literary Reference Center – via EBSCO.

- ^ Interview with Lawrence Grobel

- ^ Maranzani, Barbara (May 29, 2019). "Harper Lee and Truman Capote Were Childhood Friends Until Jealously Tore Them Apart". Biography.

- ^ "Truman Capote's previously unknown boyhood tales published". The Guardian. October 9, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, A. (2015). " Early stories of Truman Capote, book review". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ^ "UNL |". Prairie Schooner. July 23, 2009. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Hill, Pati. "Truman Capote, The Art of Fiction No. 17". The Paris Review. 16 (Spring–Summer 1957). ISSN 0031-2037. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ "Modern Library: Summer Crossing excerpt". Archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

- ^ The details of the emergence of this manuscript have been recounted by Capote's executor, Alan U. Schwartz, in the afterword to the novel's publication.

- ^ Child, Ben (May 17, 2013). "Scarlett Johansson to make directorial debut with Truman Capote adaptation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 11, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "2. Truman Capote". Warholstars.org. July 3, 1952. Archived from the original on February 22, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Andy Warhol biography Archived March 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (1988). "Chapter 28". Capote: A Biography. Fresno, CA: Linden Pub. ISBN 9780671228118.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (1988). "Chapter 39". Capote: A Biography. Fresno, CA: Linden Pub. ISBN 9780671228118.

- ^ "Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir, With The Lost Photographs of David Attie". Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (January 8, 2016). "Stories of Brooklyn, From Gowanus to the Heights". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ MacNeille, Suzanne (September 17, 2015). "Patti Smith, Paul Theroux and Others on Places Near and Far". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ "2016 Indie Book Awards". Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Capote, Truman (1987). Truman Capote - Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 144–5.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald, Capote: A Biography, 1988, Simon & Schuster: p308.

- ^ Plimpton, George, editor, Truman Capote, 1997, Doubleday: p162-163.

- ^ "Truman Capote's Papers". Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ Roy Newquist, Counterpoint, (Chicago, 1964), p. 79

- ^ "Kansas Farmer Slain". The New York Times. November 16, 1959. p. 39. Archived from the original on February 5, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Truman Capote; Jann Wenner (1973). M. Thomas Inge (ed.). Truman Capote: Conversations. Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi (published 1987). p. 297.

- ^ "Great Moments". San Francisco Film Festival. History.sffs.org (published May 4, 2006). 1974. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ George Plimpton (1998). Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-385-49173-0.

- ^ Hood, Michael (Winter 1998–1999). "True Crime Doesn't Pay: A Conversation with Jack Olsen". Point No Point. Jackolsen.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Van Jensen (April 3, 2005). "Writing history: Capote's novel has lasting effect on journalism". Journal World. Lawrence, Kansas. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Helliker, Kevin (February 19, 2013). "Long-Lost Files Cast Doubt on In Cold Blood". The Wall Street Journal. In Depth (Europe ed.). pp. 14+.

- ^ Peter Gillman; Leni Gillman (June 21, 1992). "Hoax: Secrets that Truman Capote took to the grave" (PDF). The New York Times. An investigation for the Sunday Times Magazine. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ Gore Vidal (1995). Palimpsest. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-44038-3.

- ^ Davis, Deborah (April 25, 2006). "The inside story of Truman Capote's masked ball". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ Darwish, Meaghan (February 1, 2024). "'Feud: Capote Vs. The Swans': What's Fact & What's Fiction in the FX Series?". TV Insider. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (September 10, 1987). "Books of the Times". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Sam Kashner (December 2012). "Capote's Swan Dive". Vanity Fair. pp. 200–214. Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Craig (November 19, 2021). "How Truman Capote Betrayed His High-Society 'Swans'". The New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (January 3, 2012). "Bye Society". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 10, 2022. (Reprinted from April 1988 issue.)

- ^ Truman Capote (1994). Answered Prayers. New York, NY: Random House. p. 139.

- ^ Truman Capote (1994). Answered Prayers. New York, NY: Random House. p. 151.

- ^ ""Any sort of drug distorts it." Truman Capote on writing under the influence". Literary Hub. September 30, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ "The Self-Destructive Spiral of Truman Capote After Answered Prayers". Vanity Fair. November 15, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ Abcarian, Robin (November 5, 2006). "The Personal Effects of Truman Capote A Friendship Survived More Than One Fall From Grace". The Washington Post.

- ^ Capote, Truman (1983). "Remembering Tennessee". Playboy.

- ^ "Truman Capote is Dead at 59; Novelist of Style and Clarity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

Truman Capote, one of the postwar era's leading American writers, whose prose shimmered with clarity and quality, died yesterday in Los Angeles at the age of 59.

- ^ Gay & lesbian biography Archived June 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine By Michael J. Tyrkus St. James Press, 1997 ISBN 1-55862-237-3, ISBN 978-1-55862-237-1 p. 109

- ^ Jay Parini (October 13, 2015). Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-385-53757-5. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Fact Sheet". Morbid-curiosity.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ "Capote - Dunphy Monument at Crooked Pond". Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ "TRUMAN CAPOTE ASHES - Price Estimate: $4000 - $6000". Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ "Capote Ruled Guilty of Contempt". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. October 20, 1970. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Capote Trust Is Formed To Offer Literary Prizes," The New York Times, March 25, 1994.

- ^ Grzesiak, Rich (1987). "My Significant Other, Truman Capote". Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ Solomon, Jeff (Summer 2008). "Capote and the Trillings: Homophobia and Literary Culture at Midcentury". Twentieth Century Literature. 54 (2): 129–165. doi:10.1215/0041462X-2008-3001. JSTOR 20479846.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (2005). Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote (excerpt). Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-70241-9. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Barry Werth (2001). The Scarlet Professor: Newton Arvin: A Literary Life Shattered by Scandal. New York: Doubleday. pp. 61–66, 108–13.

- ^ Dunphy, Jack (June 1987). "Dear Genius ..." A Memoir of My Life with Truman Capote. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-018317-9.

- ^ Diliberto, Gioia (October 15, 1984). "Truman Capote's Lover Jack Dunphy Remembers "My Little Friend"". People. Vol. 22, no. 16. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Truman Capote Had a Troubled Love Life. But 'Feud' Tells a (Slightly) Different Story". Esquire. February 29, 2024. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "An Unfinished Truman Capote Story from the 1950s Is Published for the First Time". Town & Country. September 22, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Colacello 1990, pp. 357, 400.

- ^ Jeffers, Juliette (February 6, 2024). "Truman Capote and Andy Warhol Hit the Turtle Bay Health Club". Interview Magazine. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c Warhol, Andy; Hackett, Pat (1989). The Andy Warhol Diaries. New York, NY: Warner Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-446-51426-2.

- ^ a b Clarke, Gerald (1989). Capote: A Biography. London: Cardinal. pp. 442, 508. ISBN 978-0-7474-0352-4.

- ^ "Truman Capote Exhibit".

- ^ Holden, Stephen (December 5, 1997). "From Capote's First Novel: The Murky Ambiguity of Southern Gothic". The New York Times. p. E10. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "The Grass Harp". IMDb. 1995. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Marks, Justin (February 18, 2014). "A Visit with Truman Capote". Maysles Films Inc. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Kelleher, Terry (December 15, 1997). "Picks and Pans Review: Biography: Truman Capote: the Tiny Terror". People. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Deming, Mark (2016). "Biography: Truman Capote - The Tiny Terror (2005)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Gilbey, Ryan (January 26, 2021). "The Capote Tapes: inside the scandal ignited by Truman's explosive final novel". The Guardian. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ "Robert Morse Tony Awards Info". Broadway World. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "Toronto Tru Delays Opening". Playbill. May 23, 1996. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012.

- ^ {{cite 1. https://arkvalleyvoice.com/the-wind-is-us-chronicles-the-life-of-truman-capote-at-box-of-bubbles-tonight/ 2. https://app.arts-people.com/index.php?show=161991 3. https://trumancapote.org/}}

- ^ Staksteder, Jack (2000). "Isnt she great 2000 imdb". IMDb. Archived from the original on March 12, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ a b "Michael J. Burg". IMDb. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Morse". Television Academy. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (August 17, 2022). "'Feud' Season 2 at FX Casts Tom Hollander as Truman Capote, Adds Calista Flockhart and Diane Lane (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "Everything We Know So Far About 'Feud: Capote vs. The Swans'". Vogue. August 18, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ Benjamin, Melanie (2016). The Swans of Fifth Avenue: A Novel (1st ed.). New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0345528698.

- ^ Preston, Caroline (February 1, 2016). "'The Swans of Fifth Avenue' review: Would you trust Truman Capote?". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Clarke, Gerald (1988) Capote: A Biography. Simon and Schuster. Bestselling and critically acclaimed biography. Basis for the 2005 film Capote.

- Colacello, Bob (1990). Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. HarperCollins. Contains many anecdotes regarding Capote's association with Warhol, and an entire chapter on Capote's relationship with Interview magazine and how it led to the writing of Music For Chameleons.

- Garson, Helen S. Truman Capote: A Study of the Short Fiction. Boston; Twayne, 1992.

- Grobel, Lawrence (1985) "Conversations with Capote. NAL.

- Hill, Pati (Spring–Summer 1957). "Truman Capote: The Art of Fiction No. 17". The Paris Review. Vol. 16.

- Inge, M. Thomas (1987) Truman Capote Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. Interviews with Capote by Gerald Clarke, David Frost, Eric Norden, George Plimpton, Gloria Steinem, Jerry Tallmer, Eugene Walter, Andy Warhol, Jann Wenner and others. ISBN 0-87805-274-7

- Krebs, Albin (August 28, 1984). "Truman Capote Is Dead at 59; Novelist of Style and Clarity". The New York Times.

- Laing, Olivia (2015). "On the threshold: the early stories of Truman Capote", in New Statesman, November 6, 2015.

- Lamparski, Richard (2006) Manhattan Diary. BearManor Media. ISBN 1-59393-054-2

- Lish, Gordon. Dear Mr. Capote. This first novel by Lish tells the story of a serial killer who wants Truman Capote to write his biography. In the letter the killer writes to Capote the details of his life, and reveals his modus operandi.[citation needed]

- Johnson, Thomas S., (1974) "The Horror in the Mansion: Gothic Fiction in the works of Truman Capote." Ann Arbor, Mich.: Dissertation Abstracts.

- Plimpton, George (1997) Truman Capote, In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career. Published by Nan A. Talese (imprint of Doubleday). Collection of first-hand observations about the author. Basis for the film Infamous (2006).

- Schwartz, Alan U. 2006. Afterword. In Truman Capote, Summer Crossing. Modern Library.

- Walter, Eugene, as told to Katherine Clark, foreword by George Plimpton (2001) Milking the Moon: A Southerner's Story of Life on This Planet. Crown. Actor-novelist-raconteur Walter, who first met Capote when they were children, recalled several anecdotes about Capote as an adult and as a child (when he was known as Bulldog Persons).

Archival sources

- Truman Capote papers, circa 1924–1984 Archived August 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine (16 linear feet) are housed at the New York Public Library

- Truman Capote papers, 1947–1965 (3.2 linear feet) are housed at the Library of Congress

External links

[edit]- Pati Hill (Spring–Summer 1957). "Truman Capote, The Art of Fiction No. 17". The Paris Review. Spring-Summer 1957 (16).

- Truman Capote at IMDb

- Truman Capote at the Internet Broadway Database

- Truman Capote at the Internet Off-Broadway Database