Norwich

Norwich (/ˈnɒrɪdʒ, -ɪtʃ/ ) is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about 100 mi (160 km) north-east of London, 40 mi (64 km) north of Ipswich and 65 mi (105 km) east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich City Council local authority area was estimated to be 144,000 in 2021, which was an increase from 143,135 in 2019.[3] The wider built-up area had a population of 213,166 in 2019.[1]

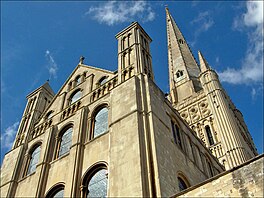

As the seat of the See of Norwich, the city has one of the country's largest medieval cathedrals. For much of the second millennium, from medieval to just before industrial times, Norwich was one of the most prosperous and largest towns of England; at one point, it was second only to London.[4] Today, it is the largest settlement in East Anglia.[4]

Heritage and status

[edit]Norwich claims to be the most complete medieval city in the United Kingdom.[5] It includes cobbled streets such as Elm Hill, Timber Hill and Tombland; ancient buildings such as St Andrew's Hall; half-timbered houses such as Dragon Hall, The Guildhall and Strangers' Hall; the Art Nouveau of the 1899 Royal Arcade; many medieval lanes; and the winding River Wensum that flows through the city centre towards Norwich Castle.[5]

In May 2012, Norwich was designated England's first UNESCO City of Literature.[6] One of the UK's popular tourist destinations, it was voted by The Guardian in 2016 as the "happiest city to work in the UK"[7] and in 2013 as one of the best small cities in the world by The Times Good University Guide.[8] In 2018, 2019 and 2020, Norwich was voted one of the "Best Places To Live" in the UK by The Sunday Times.[9][10]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The capital of the Iceni tribe was a settlement located near to the village of Caistor St Edmund on the River Tas about 5 mi (8 km) to the south of modern Norwich.[11] After an uprising led by Boudica in about 60 CE, the Caistor area became the Roman capital of East Anglia named Venta Icenorum, literally "marketplace of the Iceni".[11] This fell into disuse about 450 CE.

The Anglo-Saxons settled the site of the modern city some time between the 5th and 7th centuries,[12] founding the towns of Northwic ("North Farm"), from which Norwich takes its name,[13] and Westwic (at Norwich-over-the-Water) and a lesser settlement at Thorpe. Norwich became settled as a town in the 10th century and then became a prominent centre of East Anglian trade and commerce.[citation needed]

Early English and Norman conquest

[edit]

It is possible that three separate early Anglo-Saxon settlements, one north of the river and two either side on the south, joined as they grew; or that a single Anglo-Saxon settlement, north of the river, emerged in the mid-7th century after the abandonment of the previous three. The ancient city was a thriving centre for trade and commerce in East Anglia in 1004 when it was raided and burnt by Swein Forkbeard, the Viking king of Denmark. Mercian coins and shards of pottery from the Rhineland dating from the 8th century suggest that long-distance trade was happening long before this. Between 924 and 939, Norwich became fully established as a town, with its own mint. The word Norvic appears on coins across Europe minted during this period, in the reign of King Athelstan. The Vikings were a strong cultural influence in Norwich for 40 to 50 years at the end of the 9th century, setting up an Anglo-Scandinavian district near the north end of present-day King Street. At the time of the Norman Conquest, the city was one of the largest in England. The Domesday Book states that it had approximately 25 churches and a population of between 5,000 and 10,000. It also records the site of an Anglo-Saxon church in Tombland, the site of the Saxon market place and the later Norman cathedral. Norwich continued to be a major centre for trade, described officially as the Port of Norwich. Quern stones and other artefacts from Scandinavia and the Rhineland have been found during excavations in Norwich city centre. These date from the 11th century onwards.

Norwich Castle was founded soon after the Norman Conquest.[14] The Domesday Book records that 98 Saxon homes were demolished to make way for the castle.[15] The Normans established a new focus of settlement around the Castle and the area to the west of it: this became known as the "New" or "French" borough, centred on the Normans' own market place, which survives today as Norwich Market, the largest permanent undercover market in Europe.[5]

In 1096, Herbert de Losinga, Bishop of Thetford, began construction of Norwich Cathedral. The chief building material for the Cathedral was limestone, imported from Caen in Normandy. To transport the building stone to the site, a canal was cut from the river (from the site of present-day Pulls Ferry) up to the east wall. Herbert de Losinga then moved his See there, to what became the cathedral church for the Diocese of Norwich. The Bishop of Norwich still signs himself Norvic. Norwich received a royal charter from Henry II in 1158, and another from Richard the Lionheart in 1194. After a riot in the city in 1274, Norwich has the distinction of being the only complete English city to be excommunicated by the Pope.[16]

Middle Ages

[edit]The first recorded presence of Jews in Norwich is 1134.[17] In 1144, the Jews of Norwich were falsely accused of ritual murder after a boy (William of Norwich) was found dead with stab wounds.[17] William acquired the status of martyr and was subsequently canonised. Pilgrims made offerings to a shrine at the Cathedral (largely finished by 1140) up to the 16th century, but the records suggest there were few of them.[18] In 1174, Norwich was sacked by the Flemings. In February 1190, all the Jews of Norwich were massacred except for a few who found refuge in the castle. At the site of a medieval well, the bones of 17 individuals, including 11 children, were found in 2004 by workers preparing the ground for construction of a Norwich shopping centre. The remains were determined by forensic scientists to be most probably the remains of such murdered Jews, and a DNA expert determined that the victims were all related so that they probably came from one Ashkenazi Jewish family.[19] The study of the remains featured in an episode of the BBC television documentary series History Cold Case.[20] A research paper from 30 August 2022 confirmed the remains were most likely Ashkenazi Jews. The paper found that many of the victims had certain medical disorders most often seen in Ashkenazi communities, suggesting that a population bottleneck had occurred among Ashkenazim before the 12th century.[21] This challenged traditional views among historians that the bottleneck had happened between the 14th and 16th centuries.[22][23]

In 1216, the castle fell to Louis, Dauphin of France, and Hildebrand's Hospital was founded, followed ten years later by the Franciscan Friary and Dominican Friary. The Great Hospital dates from 1249 and the College of St Mary in the Field from 1250. In 1256, Whitefriars was founded. In 1266 the city was sacked by the "Disinherited". It has the distinction of being the only English city ever to be excommunicated, following a riot between citizens and monks in 1274.[16]

From 1280 to 1340 the city walls were built. At around 2+1⁄2 mi (4.0 km), these walls, along with the river, enclosed a larger area than that of the City of London. However, when the city walls were constructed it was made illegal to build outside them, inhibiting the expansion of the city. Part of these walls remains standing today. Around this time, the city was made a county corporate and became the seat of one of the most densely populated and prosperous counties of England. The engine of trade was wool from Norfolk's sheepwalks. Wool made England rich, and the staple port of Norwich "in her state doth stand With towns of high'st regard the fourth of all the land", as Michael Drayton noted in Poly-Olbion (1612). The wealth generated by the wool trade throughout the Middle Ages financed the construction of many fine churches, so that Norwich still has more medieval churches than any other city in Western Europe north of the Alps. Throughout this period Norwich established wide-ranging trading links with other parts of Europe, its markets stretching from Scandinavia to Spain and the city housing a Hanseatic warehouse. To organise and control its exports to the Low Countries, Great Yarmouth, as the port for Norwich, was designated one of the staple ports under the terms of the 1353 Statute of the Staple.

Early modern period (1485–1640)

[edit]Hand-in-hand with the wool industry, this key religious centre experienced a Reformation significantly different from that in other parts of England. The magistracy in Tudor Norwich unusually found ways of managing religious discord whilst maintaining civic harmony.[24]

The summer of 1549 saw an unprecedented rebellion in Norfolk. Unlike popular challenges elsewhere in the Tudor period, it appears to have been Protestant in nature. For several weeks, rebels led by Robert Kett camped outside Norwich on Mousehold Heath and took control of the city on 29 July 1549 with the support of many of its poorer inhabitants. Kett's Rebellion was particularly in response to the enclosure of land by landlords, leaving peasants with nowhere to graze their animals, and the general abuses of power by the nobility. The uprising ended on 27 August when the rebels were defeated by an army. Kett was convicted of treason and hanged from the walls of Norwich Castle.[25][26][27]

Unusually in England, the rebellion divided the city and appears to have linked Protestantism with the plight of the urban poor. In the case of Norwich, this process was underscored later by the arrival of Dutch and Flemish "Strangers" fleeing persecution from the Catholics and eventually numbering as many as one-third of the city's population.[28] Large numbers of such exiles came to the city, especially Flemish Protestants from the Westkwartier ("Western Quarter"), a region in the Southern Netherlands where the first Calvinist fires of the Dutch Revolt had spread. Inhabitants of Ypres, in particular, chose Norwich above other destinations.[29] Perhaps in response to Kett, Norwich became the first provincial city to initiate compulsory payments for a civic scheme of poor relief, which it has been claimed led to its wider introduction, forming the basis of the later Elizabethan Poor Law of 1597–1598.[30]

Norwich has traditionally been the home of various minorities, notably Flemish and Belgian Walloon communities in the 16th and 17th centuries. The great "stranger" immigration of 1567 brought a substantial Flemish and Walloon community of Protestant weavers to Norwich, where they are said to have been made welcome.[31] The merchant's house which was their earliest base in the city — now a museum — is still known as Strangers' Hall. It seems that the strangers integrated into the local community without much animosity, at least among the business fraternity, who had the most to gain from their skills. Their arrival in Norwich boosted trade with mainland Europe and fostered a movement towards religious reform and radical politics in the city. By contrast, after being persecuted by the Anglican church for his Puritan beliefs, Michael Metcalf, a 17th-century Norwich weaver, fled the city and settled in Dedham, Massachusetts.[32]

The Norwich Canary was first introduced into England by Flemings fleeing from Spanish persecution in the 16th century. Along with their advanced techniques in textile working, they brought pet canaries, which they began to breed locally, eventually becoming in the 20th century a mascot of the city and the emblem of its football club, Norwich City F.C.: "The Canaries". Printing was introduced to the city in 1567 by Anthony de Solempne, one of the strangers, but it did not take root and had died out by about 1572.[33] Norwich's coat of arms was first recorded in 1562. It is described as: Gules a Castle triple-towered and domed Argent in base a Lion passant guardant [or Leopard] Or. The castle is supposed to represent Norwich Castle and the lion, taken from the Royal Arms of England, may have been granted by King Edward III.[34]

Civil War to Victorian era

[edit]In the English Civil War, across the Eastern Counties, Oliver Cromwell's powerful Eastern Association was eventually dominant. However, to begin with, there had been a large element of Royalist sympathy within Norwich, which seems to have experienced a continuity of its two-sided political tradition throughout the period. Bishop Matthew Wren was a forceful supporter of Charles I. Nonetheless, Parliamentary recruitment took hold. The strong Royalist party was stifled by a lack of commitment from the aldermen and isolation from Royalist-held regions.[35] Serious inter-factional disturbances culminated in "The Great Blow" of 1648 when Parliamentary forces tried to quell a Royalist riot. The latter's gunpowder was set off by accident in the city centre, causing mayhem. According to Hopper,[36] the explosion "ranks among the largest of the century". Stoutly defended though East Anglia was by the Parliamentary army, there were said to have been pubs in Norwich where the king's health was still drunk and the name of the Protector sung to ribald verse.

At the cost of some discomfort to the Mayor, the moderate Joseph Hall was targeted because of his position as Bishop of Norwich. Norwich was marked in the period after the Restoration of 1660 and the ensuing century by a golden age of its cloth industry, comparable only to those in the West Country and Yorkshire,[37] but unlike other cloth-manufacturing regions, Norwich weaving brought greater urbanisation, mainly concentrated in the surrounds of the city itself, creating an urban society, with features such as leisure time, alehouses and other public forums of debate and argument.[38]

Norwich in the late 17th century was riven politically. Churchman Humphrey Prideaux described "two factions, Whig and Tory, and both contend for their way with the utmost violence."[39] Nor did the city accept the outcome of the 1688 Glorious Revolution with a unified voice. The pre-eminent citizen, Bishop William Lloyd, would not take the oaths of allegiance to the new monarchs. One report has it that in 1704 the landlord of Fowler's alehouse "with a glass of beer in hand, went down on his knees and drank a health to James the third, wishing the Crowne [sic] well and settled on his head."[40]

Writing of the early 18th century, Pound describes the city's rich cultural life, the winter theatre season, the festivities accompanying the summer assizes, and other popular entertainments. Norwich was the wealthiest town in England, with a sophisticated system of poor relief, and a large influx of foreign refugees.[41] Despite severe outbreaks of plague, the city had a population of almost 30,000. This made Norwich unique in England, although there were some 50 cities of similar size in Europe. In some, like Lyon and Dresden, this was, as in the case of Norwich, linked to an important proto-industry, such as textiles or china pottery, in some, such as Vienna, Madrid and Dublin, to the city's status as an administrative capital, and in some such as Antwerp, Marseilles and Cologne to a position on an important maritime or river trade route.[a]

In 1716, at a play at the New Inn, the Pretender was cheered and the audience booed and hissed every time King George's name was mentioned. In 1722 supporters of the king were said to be "hiss'd at and curst as they go in the streets," and in 1731 "a Tory mobb, in a great body, went through several parts of this city, in a riotous manner, cursing and abusing such as they knew to be friends of the government."[b] However the Whigs gradually gained control and by the 1720s they had successfully petitioned Parliament to allow all adult males working in the textile industry to take up the freedom, on the correct assumption that they would vote Whig. But it had the effect of boosting the city's popular Jacobitism, says Knights, and contests of the kind described continued in Norwich well into a period in which political stability had been discerned at a national level. The city's Jacobitism perhaps only ended with 1745, well after it had ceased to be a significant movement outside Scotland.[40] Despite the Highlanders reaching Derby and Norwich citizens mustering themselves into an association to protect the city, some Tories refused to join in, and the vestry of St Peter Mancroft resolved that it would not ring its bells to summon the defence. Still, it was the end of the road for Norwich Jacobites, and the Whigs organised a notable celebration after the Battle of Culloden.[40]

The events of this period illustrate how Norwich had a strong tradition of popular protest favouring Church and Stuarts and attached to the street and alehouse. Knights tells how in 1716 the mayoral election had ended in a riot, with both sides throwing "brick-ends and great paving stones" at each other.[40] A renowned Jacobite watering-hole, the Blue Bell Inn (nowadays The Bell Hotel), owned in the early 18th century by the high-church Helwys family, became the central rendezvous of the Norwich Revolution Society in the 1790s.[42]

Britain's first provincial newspaper, the Norwich Post, appeared in 1701. By 1726 there were rival Whig and Tory presses, and as early as mid-century, three-quarters of the males in some parishes were literate.[c] The Norwich municipal library claims an excellent collection of these newspapers, also a folio collection of scrapbooks on 18th-century Norwich politics, which Knights says are "valuable and important". Norwich alehouses had 281 clubs and societies meeting in them in 1701, and at least 138 more were formed before 1758. The Theatre Royal opened in 1758, alongside the city's stage productions in inns and puppet shows in rowdy alehouses.[43][44] In 1750 Norwich could boast nine booksellers and after 1780 a "growing number of circulating and subscription libraries".[45] Knights 2004 says: "[All this] made for a lively political culture, in which independence from governmental lines was particularly strong, evident in campaigns against the war with America and for reform... in which trade and the impact of war with Revolutionary France were key ingredients. The open and contestable structure of local government, the press, the clubs and societies, and dissent all ensured that politics overlapped with communities bound by economics, religion, ideology and print in a world in which public opinion could not be ignored."[40]

Amid this metropolitan culture, the city burghers had built a sophisticated political structure. Freemen, who had the right to trade and to vote at elections, numbered about 2,000 in 1690, rising to over 3,300 by the mid-1730s. With growth partly the result of political manipulation, their numbers did at one point reach one-third of the adult male population.[40] This was notoriously the age of "rotten" and "pocket" boroughs and Norwich was unusual in having such a high proportion of its citizens able to vote. "Of the political centres where the Jacobin propaganda had penetrated most deeply only Norwich and Nottingham had a franchise deep enough to allow radicals to make use of the electoral process."[46] "Apart from London, Norwich was probably still the largest of those boroughs which were democratically governed," says Jewson 1975, describing other towns under the control of a single fiefdom. In Norwich, he says, a powerful Anglican establishment, symbolised by the Cathedral and the great church of St Peter Mancroft was matched by scarcely less powerful congeries of Dissenters headed by the wealthy literate body [of Unitarians] worshipping at the Octagon Chapel.[47]

In the middle of political disorders of the late 18th century, Norwich intellectual life flourished. Harriet Martineau wrote of the city's literati of the period, including such people as William Taylor, one of England's first scholars of German. The city "boasted of her intellectual supper-parties, where, amidst a pedantry which would now make laughter hold both his sides, there was much that was pleasant and salutary: and finally she called herself The Athens of England."[48]

Despite Norwich's longstanding industrial prosperity, by the 1790s its wool trade had begun facing intense competition, at first from Yorkshire woollens and then, increasingly, from Lancashire cotton. The effects were aggravated by the loss of continental markets after Britain went to war with France in 1793.[d] The early 19th century saw de-industrialisation accompanied by bitter squabbles. The 1820s were marked by wage cuts and personal recrimination against owners. So amid the rich commercial and cultural heritage of its recent past, Norwich suffered in the 1790s from incipient decline exacerbated by a serious trade recession.

As early in the war as 1793, a major city manufacturer and government supporter, Robert Harvey, complained of low order books, languid trade and doubling of the poor rate.[e] Like many of their Norwich forebears, the hungry poor took their complaints onto the streets. Hayes describes a meeting of 200 people in a Norwich public house, where "Citizen Stanhope" spoke.[f] The gathering "[roared its] applause at Stanhope's declaration that the Ministers unless they changed their policy, deserved to have their heads brought to the block; – and if there was a people still in England, the event might turn out to be so." Hayes says that "the outbreak of war, in bringing the worsted manufacture almost to a standstill and so plunging the mass of the Norwich weavers into sudden distress made it almost inevitable that a crude appeal to working-class resentment should take the place of a temperate process of education which the earliest reformers had intended."[49]

At this period opposition to Pitt's government and their war came – in their case almost unanimously – from a circle of radical Dissenting intellectuals of interest in their own right. They included the Rigby, Taylor, Aitkin, Barbold, and Alderson families – all Unitarians - and some of the Quaker Gurneys (one of whose girls, Elizabeth, was later, under her married name of Fry, to become a noted campaigner for prison reform). Their activities included visits to revolutionary France (before the execution of Louis XVI), the earliest British research into German literature, studies on medical science, petitioning for parliamentary reform, and publishing a highbrow literary magazine called "The Cabinet", in 1795. Their blend of politics, religion and social campaigning was seen by Pitt and Windham as suspicious, prompting Pitt to denounce Norwich as "the Jacobin city". Edmund Burke attacked John Gurney in print for sponsoring anti-war protests. In the 1790s, Norwich was second only to London as an active intellectual centre in England, and that it did not regain that level of prominence until the University of East Anglia was established in the late 20th century.[50]

By 1795, it was not just the Norwich rabble who were causing the government concern. In April of that year, the Norwich Patriotic Society was founded, its manifesto declaring "that the great end of civil society was general happiness; that every individual had a right to share in the government."[51] In December the price of bread reached a new peak, and in May 1796, when William Windham was forced to seek re-election after his appointment as war secretary, he only just held his seat.[g] Amid the disorder and violence that was such a common feature of Norwich election campaigns, it was only by the narrowest margin that the radical Bartlett Gurney ("Peace and Gurney – No More War – No more Barley Bread") failed to unseat him.[52]

Though informed by issues of recent national importance, the bipartisan political culture of Norwich in the 1790s cannot be divorced from local tradition. Two features stand out from a political continuum of three centuries. The first is a dichotomous power balance. From at least the time of the Reformation, Norwich was recorded as a "two-party city". In the mid-16th century, the weaving parishes fell under the control of opposition forces, as Kett's rebels held the north of the river, in support of poor clothworkers. Indeed there seems to be a case for saying that with this tradition of two-sided disputation, the city had steadily developed an infrastructure, evident in its many cultural and institutional networks of politics, religion, society, news media and the arts, whereby argument could be managed short of outright confrontation. Indeed, at a time of hunger and tension on the Norwich streets, with alehouse crowds ready to have "a Minister's head brought to the block", the Anglican and Dissenting clergy exerted themselves to conduct a collegial dialogue, seeking common ground and reinforcing the well-mannered civic tradition of earlier periods.

In 1797 Thomas Bignold, a 36-year-old wine merchant and banker founded the first Norwich Union Society. Some years earlier, when he moved from Kent to Norwich, Bignold had been unable to find anyone willing to insure him against the threat from highwaymen. With the entrepreneurial thought that nothing was impossible, and aware that in a city built largely of wood the threat of fire was uppermost in people's minds, Bignold formed the "Norwich Union Society for the Insurance of Houses, Stock and Merchandise from Fire". The new business, which became known as the Norwich Union Fire Insurance Office, was a "mutual" enterprise. Norwich Union would later become the country's largest insurance giant.

From earliest times, Norwich was a textile centre. In the 1780s the manufacture of Norwich shawls became an important industry[53] and remained so for nearly a hundred years. The shawls were a high-quality fashion product and rivalled those of other towns such as Paisley, which had entered shawl manufacturing in about 1805, some 20 or more years after Norwich. With changes in women's fashion in the later Victorian period, the popularity of shawls declined and eventually manufacture ceased. Examples of Norwich shawls are now sought after by collectors of textiles.

Norwich's geographical isolation was such that until 1845, when a railway link was established, it was often quicker to travel to Amsterdam by boat than to London. The railway was introduced to Norwich by Morton Peto, who also built a line to Great Yarmouth. From 1808 to 1814, Norwich had a station in the shutter telegraph chain that connected the Admiralty in London to its naval ships in the port of Great Yarmouth. A permanent military presence was established in the city with the completion of Britannia Barracks in 1897.[54] The Bethel Street and Cattle Market Street drill halls were built around the same time.[55]

20th century

[edit]

In the early 20th century, Norwich still had several major manufacturing industries. Among them were the large-scale and bespoke manufacture of shoes (for example the Start-rite and Van Dal brands, Bowhill & Elliott and Cheney & Sons Ltd respectively), clothing, joinery (including the cabinet makers and furniture retailer Arthur Brett and Sons, which continues in business in the 21st century), structural engineering, and aircraft design and manufacture. Notable employers included Boulton & Paul, Barnards (iron founders and inventors of machine-produced wire netting), and the electrical engineers Laurence Scott and Electromotors.

Norwich also has a long association with chocolate making, mainly through the local firm of Caley's, which began as a manufacturer and bottler of mineral water and later diversified into chocolate and Christmas crackers. The Caley's cracker-manufacturing business was taken over by Tom Smith in 1953,[56] and the Norwich factory in Salhouse Road closed in 1998. Caley's was acquired by Mackintosh in the 1930s and merged with Rowntree's in 1969 to become Rowntree-Mackintosh. Finally, it was bought by Nestlé and closed in 1996, with all operations moving to York after a Norwich association of 120 years. The demolished factory stood where the Chapelfield development is now. Caley's chocolate has since reappeared as a brand in the city, though it is no longer made there.[57]

HMSO, once the official publishing and stationery arm of the British government and one of the largest print buyers, printers and suppliers of office equipment in the UK, moved most of its operations from London to Norwich in the 1970s. It occupied the purpose-built 1968 Sovereign House building, near Anglia Square, which in 2017 stood empty and due for demolition if a long-postponed redevelopment of Anglia Square went ahead.[58]

Jarrolds, established in 1810, was a nationally well-known printer and publisher. In 2004, after nearly 200 years, the printing and publishing businesses were sold. Today, the company remains privately owned and the Jarrold name is best recognised as being that of Norwich's only independent department store. The company is also active in property development in Norwich and has a business training division.[59]

Pubs and brewing

[edit]The city had a long tradition of brewing.[60] Several large breweries continued into the second half of the 20th century, notably Morgans, Steward & Patteson, Youngs Crawshay and Youngs, Bullard and Son, and the Norwich Brewery. Despite takeovers and consolidation in the 1950s and 1960s, only the Norwich Brewery (owned by Watney Mann and on the site of Morgans) remained by the 1970s. That too closed in 1985 and was then demolished. Only microbreweries remain today.[61]

It was stated by Walter Wicks in his book that Norwich once had "a pub for every day of the year and a church for every Sunday". This was in fact significantly under the actual amount: the highest number of pubs in the city was in the year 1870, with over 780 beer-houses. A "Drink Map" produced in 1892 by the Norwich and Norfolk Gospel Temperance Union showed 631 pubs in and around the city centre. By 1900, the number had dropped to 441 pubs within the City Walls. The title of a pub for every day of the year survived until 1966, when the Chief Constable informed the Licensing Justices that only 355 licences were still operative, with the number still shrinking: over 25 had closed in the last decade.[62] In 2018, about 100 pubs remained open around the city centre.

Second World War

[edit]Norwich suffered extensive bomb damage during World War II, affecting large parts of the old city centre and Victorian terrace housing around the centre. Industry and the rail infrastructure also suffered. The heaviest raids occurred on the nights of 27/28 and 29/30 April 1942; as part of the Baedeker raids (so-called because Baedeker's series of tourist guides to the British Isles were used to select propaganda-rich targets of cultural and historic significance rather than strategic importance). Lord Haw-Haw made reference to the imminent destruction of Norwich's new City Hall (completed in 1938), although in the event it survived unscathed. Significant targets hit included the Morgan's Brewery building, Colman's Wincarnis works, City Station, the Mackintosh chocolate factory, and shopping areas including St Stephen's St and St Benedict's St, the site of Bond's department store (now John Lewis) and Curl's (later Debenhams) department store.

229 citizens were killed in the two Baedeker raids with 1,000 others injured, and 340 by bombing throughout the war — giving Norwich the highest air raid casualties in Eastern England. Out of the 35,000 domestic dwellings in Norwich, 2,000 were destroyed, and another 27,000 suffered some damage.[63] In 1945 the city was also the intended target of a brief V-2 rocket campaign, though all these missed the city itself.[64][65]

Post-war redevelopment

[edit]

As the war ended, the city council revealed what it had been working on before the war. It was published as a book – The City of Norwich Plan 1945 or commonly known as "The '45 Plan"[66] – a grandiose scheme of massive redevelopment which never properly materialised. However, throughout the 1960s to early 1970, the city was completely altered and large areas of Norwich were cleared to make way for modern redevelopment.

In 1960, the inner-city district of Richmond, between Ber Street and King Street, locally known as "the Village on the Hill", was condemned as slums and many residents were forced to leave by compulsory purchase orders on the old terraces and lanes. The whole borough demolished consisted of some 56 acres of existing streets, including 833 dwellings (612 classed as unfit for human habitation), 42 shops, four offices, 22 public houses and two schools.[67] Communities were moved to high-rise buildings such as Normandie Tower and new housing estates such as Tuckswood, which were being built at the time. A new road, Rouen Road, was developed instead, consisting mainly of light industrial units and council flats. Ber Street, a once historic main road into the city, had its whole eastern side demolished. About this time, the final part of St Peters Street, opposite St Peter Mancroft Church, were demolished along with large Georgian townhouses at the top of Bethel Street, to make way for the new City Library in 1961.[63] This burnt down on 1 August 1994 and was replaced in 2001 by The Forum.

A controversial plan was implemented for Norwich's inner ring-road in the late 1960s. In 1931, the city architect Robert Atkinson, referring to the City Wall, remarked that "in almost every position are slum dwellings put up during the last 50 years. It would be a great adventure to clear them all out and open up the road following the wall which has always been a natural highway. Do this, and you will have a wonderful circulating boulevard all around the city and its cost would be comparatively nothing."[68] To accommodate the road, many more buildings were demolished, including an ancient road junction – Stump Cross. Magdalen Street, Botolph Street, St George's Street, Calvert Street and notably Pitt Street, all lined with Tudor and Georgian buildings, were cleared to make way for a fly-over and a Brutalist concrete shopping centre – Anglia Square – as well as office blocks such as an HMSO building, Sovereign House. Other areas affected were Grapes Hill, a once narrow lane lined with 19th-century Georgian cottages, which was cleared and widened into a dual carriageway leading to a roundabout. Shortly before construction of the roundabout, the city's old Drill Hall was demolished, along with sections of the original city wall and other large townhouses along the start of Unthank Road (named after the Unthank family, local landowners).[69]

The roundabout also required the north-west corner of Chapelfield Gardens to be demolished. About a mile of Georgian and Victorian terrace houses along Chapelfield Road and Queens Road, including many houses built into the city walls, was bulldozed in 1964. This included the surrounding district off Vauxhall Street, consisting of swathes of terrace housing that were condemned as slums. This also included the whole West Pottergate district, which contained a mix of 18th and 19th-century cottages and terraced housing, pubs and shops. Post-war housing and maisonettes flats now stand where the Rookery slums once did. Some aspects of The '45 Plan were put into action, which saw large three-story Edwardian houses in Grove Avenue and Grove Road, and other large properties on Southwell Road, demolished in 1962 to make way for flat-roofed single-story style maisonettes that still stand today.[70] Heigham Hall, a large Victorian manor house off Old Palace Road was also demolished in 1963, to build Dolphin Grove flats, which housed many Norwich families displaced by slum clearance.

Other housing developments in the private and public sector took place after the Second World War, partly to accommodate the growing population of the city and to replace condemned and bomb-damaged areas, such as the Heigham Grove district between Barn Road and Old Palace Road, where some 200 terraced houses, shops and pubs were all flattened. Only St Barnabas church and one public house, The West End Retreat, now remain. Another central street bulldozed during the 1960s was St Stephens Street. It was widened, clearing away many historically significant buildings in the process, firstly for Norwich Union's new office blocks and shortly after with new buildings, after it suffered damage during the Baedeker raids. In Surrey Street, several grand six-storey Georgian townhouses were demolished to make way for Norwich Union's office. Other notable buildings that were lost were three theatres (the Norwich Hippodrome on St Giles Street, which is now a multi-storey car park, the Grosvenor Rooms and Electric Theatre in Prince of Wales Road) The Norwich Corn Exchange in Exchange Street (built 1861, demolished 1964), the Free Library in Duke Street (built 1857, demolished 1963) and the Great Eastern Hotel, which faced Norwich Station. Two large churches, the Chapel Field East Congregational church[71] (built 1858, demolished 1972) was pulled down, as well as the 100-foot (30 m) tall Presbyterian church in Theatre Street, built in 1874 and designed by local architect Edward Boardman. It has been said that more of Norwich's architecture was destroyed by the council in post-war redevelopment schemes than during the Second World War.[citation needed]

Other events

[edit]In 1976 the city's pioneering spirit was on show when Motum Road in Norwich, allegedly the scene of "a number of accidents over the years", became the third road in Britain to be equipped with sleeping policemen, intended to encourage adherence to the road's 30 mph (48 km/h) speed limit.[72] The bumps, installed at intervals of 50 and 150 yards (46 and 137 m), stretched 12 feet (3.7 m) across the width of the road and their curved profile was, at its highest point, 4 in (10 cm) high.[72] The responsible quango gave an assurance that the experimental devices would be removed not more than one year after installation.[72]

From 1980 to 1985 the city became a frequent focus of national media due to squatting in Argyle Street, a Victorian street that was demolished in 1986, despite being the last street to survive the Richmond Hill redevelopment. On 23 November 1981, a minor F0/T1 tornado struck Norwich as part of a record-breaking nationwide tornado outbreak, causing minor damage in Norwich city centre and surrounding suburbs.[73]

Governance

[edit]

There are two tiers of local government covering Norwich, at district and county level: Norwich City Council and Norfolk County Council. The city council manages services such as housing, planning, leisure and tourism, and is based at City Hall overlooking Norwich Market in the city centre. The county council manages services such as schools, transport, social services and libraries across Norfolk.[74] There are no civil parishes in Norwich, with the whole city being an unparished area.[75]

Lord mayoralty and shrievalty

[edit]

The ceremonial head of the city is the Lord Mayor; though now simply a ceremonial position, in the past the office carried considerable authority, with executive powers over the finances and affairs of the city council. The office of Mayor of Norwich dates from 1403 and was raised to the dignity of lord mayor in 1910 by Edward VII "in view of the position occupied by that city as the chief city of East Anglia and of its close association with His Majesty".[76][77] The title was regranted on local government reorganisation in 1974.[78] From 1404 the citizens of Norwich, as a county corporate, had the privilege of electing two sheriffs. Under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 this was reduced to one and became a ceremonial post. Both Lord Mayor and Sheriff are elected for a year's term of office at the council's annual meeting, but the term of office was temporarily extended to two years for the periods 2019-2021 and 2021-2023, the normal annual elections having been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic in the years 2020-2022.[79][76][80]

Westminster

[edit]Since 1298 Norwich has returned two members of Parliament to the House of Commons. Until 1950 the city was an undivided constituency, returning two MPs. Since that date, the area has been two single-member constituencies: Norwich North and Norwich South.[81] Both proved to be marginal seats in recent elections until 2010, switching between the Labour and Conservative parties.

Norwich North, which includes some rural wards of Broadland District, was held by Labour from 1950 to 1983 when it was gained by the Conservatives. Labour regained the seat in 1997, holding it until a by-election in 2009. The current MP is the Conservative, Chloe Smith, who held the seat in the 2015 General Election.[82] Norwich South, which includes part of South Norfolk District, was held by Labour from February 1974 to 1983, when it was gained by the Conservatives. John Garrett regained the seat for Labour in 1987. Charles Clarke became Labour MP for Norwich South in 1997.[83] In the 2010 General Election, Labour lost the seat to the Liberal Democrats, with Simon Wright becoming MP.[84] At the 2015 General Election, Clive Lewis regained the seat for Labour.[85] In both the 2017 General Election and 2019 General Election, the two incumbent 2015 MPs held their seats.[86]

Demography

[edit]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [87][88] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

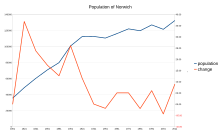

The 2021 United Kingdom census reported a resident population for the City of Norwich of approximately 144,000, a 8.7 per cent increase over the 2011 census.[3] The urban, built-up area of Norwich had a population of 213,166 according to the 2011 census.[89] This area extends beyond the city boundary, with extensive suburban areas on the western, northern and eastern sides, including Costessey, Taverham, Hellesdon, Bowthorpe, Old Catton, Sprowston and Thorpe St Andrew. The parliamentary seats cross over into adjacent local-government districts. The population of the Norwich travel to work area (i. e. the self-contained labour-market area in and around Norwich in which most people live and commute to work) was estimated at 282,000 in 2009.[90] Norwich is one of the most densely populated local-government districts in the East of England, with 3,690 people per square kilometre (9,600 people/sq mi).[91]

In 2022 the ethnic composition of Norwich's population was 87.1% White, 5.5% Asian, 3.2% of mixed race, 2.6% Black, 0.6% Arab and 1.1% of other ethnic heritage.[92] In religion, 33.6% of the population are Christian, 3% Muslim, 1.2% Hindu, 0.7% Buddhist, 0.2% Jewish, 0.1% Sikh, 0.9% of another religion, 53.5% with no religion and 6.8% unwilling to state their religion.[93] In the 2001 and 2011 censuses, Norwich was found to be the least religious city in England, with the highest proportion of respondents with no reported religion, compared to 25.1% across England and Wales.[94] The largest quinary group consists of the 20 to 24-year-olds (14.6%) because of the high university student population.[95]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnic group | 1991[96] | 2001[97] | 2011[98] | 2021[92] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 118,843 | 98.3% | 117,701 | 96.8% | 120,375 | 90.9% | 125,421 | 87.1% |

| White: British | – | – | 113,600 | 93.5% | 112,237 | 84.7% | 111,623 | 77.6% |

| White: Irish | – | – | 843 | 874 | 0.7% | 885 | 0.6% | |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | – | – | 127 | 0.1% | 214 | 0.1% |

| White: Roma | – | – | – | – | – | – | 214 | 0.1% |

| White: Other | – | – | 3,258 | 7,137 | 5.4% | 12,485 | 8.7% | |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 1,010 | 0.8% | 1,506 | 1.2% | 5,844 | 4.5% | 7,867 | 5.5% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 314 | 525 | 1,684 | 1.3% | 2,570 | 1.8% | ||

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 78 | 93 | 255 | 0.2% | 528 | 0.4% | ||

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 123 | 216 | 540 | 0.4% | 839 | 0.6% | ||

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 286 | 468 | 1,679 | 1.3% | 1,627 | 1.1% | ||

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | 209 | 204 | 1,686 | 1.3% | 2,303 | 1.6% | ||

| Black or Black British: Total | 506 | 0.4% | 433 | 0.4% | 2,147 | 1.6% | 3,578 | 2.6% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | 98 | 123 | 272 | 0.2% | 395 | 0.3% | ||

| Black or Black British: African | 168 | 267 | 1,727 | 1.3% | 2,807 | 2.0% | ||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | 240 | 43 | 148 | 0.1% | 376 | 0.3% | ||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | 1,321 | 1.1% | 3,039 | 2.3% | 4,519 | 3.2% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | 311 | 684 | 0.5% | 939 | 0.7% | |

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | 187 | 660 | 0.5% | 966 | 0.7% | |

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | 391 | 876 | 0.7% | 1,287 | 0.9% | |

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | 432 | 819 | 0.6% | 1,327 | 0.9% | |

| Other: Total | 536 | 0.4% | 589 | 0.5% | 1,107 | 0.9% | 2,539 | 1.7% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | 643 | 0.5% | 900 | 0.6% |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 536 | 0.4% | 589 | 0.5% | 464 | 0.4% | 1,639 | 1.1% |

| Total | 120,895 | 100% | 121,550 | 100% | 132,512 | 100% | 143,924 | 100% |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | 2001[99] | 2011[100] | 2021[93] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Holds religious beliefs | 76,108 | 62.6 | 65,417 | 49.4 | 57,189 | 39.7 |

| 73,428 | 60.4 | 59,515 | 44.9 | 48,399 | 33.6 | |

| 485 | 0.4 | 978 | 0.7 | 983 | 0.7 | |

| 348 | 0.3 | 1,017 | 0.8 | 1,719 | 1.2 | |

| 239 | 0.2 | 241 | 0.2 | 331 | 0.2 | |

| 887 | 0.7 | 2,612 | 2.0 | 4,289 | 3.0 | |

| 102 | 0.1 | 168 | 0.1 | 185 | 0.1 | |

| Other religion | 619 | 0.5 | 886 | 0.7 | 1283 | 0.9 |

| (No religion and Religion not stated) | 45,442 | 37.4 | 67,095 | 50.7 | 86,733 | 60.3 |

| No religion | 33,766 | 27.8 | 56,268 | 42.5 | 76,973 | 53.5 |

| Religion not stated | 11,676 | 9.6 | 10,827 | 8.2 | 9,760 | 6.8 |

| Total population | 121,550 | 100.0 | 132,512 | 100.0 | 143,922 | 100.0 |

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary

[edit]The city has 56 primary schools (including 16 academies and free schools) and 13 secondary schools, 11 of which are academies.[101] The city's eight independent schools include Norwich School and Norwich High School for Girls.[101] There are five schools for children with learning disabilities.[102] The former Norwich High School for Boys in Upper St Giles Street has a blue plaque commemorating Sir John Mills, who was a pupil there.[103]

Universities and colleges

[edit]

Norwich has two universities: the University of East Anglia and Norwich University of the Arts. The student population is around 15,000, many of them from overseas.[104] The University of East Anglia, founded in 1963, is located on the outskirts of the city. It has a creative writing programme, established by Malcolm Bradbury and Angus Wilson, whose graduates include Kazuo Ishiguro and Ian McEwan. It has done work on climate research and climate change. Its campus is home to the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, which houses several important art collections. The Norwich University of the Arts dates back to 1845 as the Norwich School of Design. Founded by artists and followers of the Norwich School art movement, it was founded to provide designers for local industries. Previously a specialist art school (the Norwich School of Art and Design), it achieved university status in 2013.

Norwich has three further education colleges. City College Norwich, situated on Ipswich Road, was founded in 1891 and is one of the largest such colleges in the country.[105] Access to Music is located on Magdalen Street at Epic Studios, and Easton & Otley College's Easton Campus is located 7 mi (11 km) west of the city.[106]

Culture and attractions

[edit]Historically Norwich has been associated with art, literature and publishing. This continues. It was the site of England's first provincial library, which opened in 1608, and the first city to implement the Public Libraries Act 1850.[107] The Norwich Post was the first provincial newspaper outside London, founded in 1701.[107] The Norwich School of artists was the first provincial art movement, with nationally acclaimed artists such as John Crome associated with the movement.[108] Other literary firsts include Julian of Norwich's Revelations of Divine Love, published in 1395, which was the first book written in the English language by a woman, and the first poem written in blank verse, composed by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in the 16th century.[107]

Today the city is a regional centre for publishing, with 5 per cent of the UK's independent publishing sector based in the city in 2012.[107] In 2006 Norwich became the UK's first City of Refuge, part of the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) which promotes free speech.[107] Norwich made the shortlist for the first city to be designated UK City of Culture, but in July 2010 it was announced that Derry had been selected.[109] In May 2012 Norwich was designated as England's first UNESCO City of Literature.[110]

Attractions

[edit]

Norwich is a popular destination for a city break. Attractions include Norwich Cathedral, the cobbled streets and museums of old Norwich, Norwich Castle, Cow Tower, Dragon Hall and The Forum. Norwich is one of the UK's top ten shopping destinations, with a mix of chain retailers and independent stores, and Norwich Market as one of the largest outdoor markets in England.

The Forum, designed by Michael Hopkins and Partners and opened in 2002 is a building designed to house the Norfolk and Norwich Millennium Library, a replacement for the Norwich Central Library building which burnt down in 1994, and the regional headquarters and television centre for BBC East. In 2006–2013 it was the most visited library in the UK, with 1.3 million visits in 2013.[111] The collections contains the 2nd Air Division Memorial Library, a collection of material about American culture and the American relationship with East Anglia, especially the role of the United States Air Force on UK airbases throughout the Second World War and Cold War. Much of the collection was lost in the 1994 fire, but the collection has been restored by contributions from many veterans of the war, European and American. The building also provides a venue for art exhibitions, concerts and events, although the city still lacks a dedicated concert venue.

Recent attempts to shed the backwater image of Norwich and market it as a popular tourist destination, as well as a centre for science, commerce, culture and the arts, have included refurbishment of the Norwich Castle Museum and the opening of the Forum. The proposed new slogan for Norwich as England's Other City has been the subject of much discussion and controversy. It remains to be seen whether it will be adopted. Several signs at the city's approaches still display the traditional phrase: "Norwich — a fine city".

The city promotes its architectural heritage through a collection of notable buildings in Norwich called the "Norwich 12". The group consists of: Norwich Castle, Norwich Cathedral, the Great Hospital, St Andrew's Hall and Blackfriars' Hall, The Guildhall, Dragon Hall, The Assembly House, St James Mill, St John the Baptist RC Cathedral, Surrey House, City Hall and The Forum.

Art and music

[edit]Each year the Norfolk and Norwich Festival celebrates the arts, drawing many visitors into the city from all over eastern England. The Norwich Twenty Group, founded in 1944, presents exhibitions of its members to promote awareness of modern art. Norwich was home to the first arts festival in Britain in 1772.[112]

Norwich Arts Centre is a notable live music venue, concert hall and theatre located in St Benedict's Street. The King of Hearts in Fye Bridge Street is another centre for art and music. Norwich has a thriving music scene based around local venues such as the University of East Anglia LCR, Norwich Arts Centre, The Waterfront and Epic Studios. Live music, mostly contemporary musical genres, is also to be heard at a number of other public house and club venues around the city. The city is host to many artists that have achieved national and international recognition such as Cord, The Kabeedies, Serious Drinking, Tim Bowness, Sennen, Magoo, Let's Eat Grandma and KaitO.

Norwich hosted BBC Radio 1's Big Weekend in 2015. The event was held on 23–24 May in Earlham Park.[113]

Established record labels in Norwich include All Sorted Records,[114] NR ONE,[115] Hungry Audio and Burning Shed.

The British artist Stella Vine lived in Norwich from the age of seven,[116] including for a short while in Argyle Street, Norwich and again later in life with her son Jamie. Vine depicted the city in a large painting, Welcome to Norwich a fine city (2006).[117]

Theatres

[edit]

Norwich has theatres ranging in capacity from 100 to 1,300 seats and offering a wide variety of programmes. The Theatre Royal is the largest and has been on its present site for nearly 250 years, through several rebuildings and many alterations. It has 1,300 seats and hosts a mix of national touring productions including musicals, dance, drama, family shows, stand-up comedians, opera and pop.

The Maddermarket Theatre opened in 1921 as the first permanent recreation of an Elizabethan theatre. The founder was Nugent Monck who had worked with William Poel. The theatre is a Shakespearean-style playhouse and has a seating capacity of 310. Norwich Puppet Theatre was founded in 1979 by Ray and Joan DaSilva as a permanent base for their touring company and was first opened as a public venue in 1980, following the conversion of the medieval church of St James in the heart of Norwich. Under subsequent artistic directors — Barry Smith and Luis Z. Boy — the theatre established its current pattern of operation. It is a nationally unique venue dedicated to puppetry, and currently houses a 185-seat raked auditorium, the 50-seat Octagon Studio, workshops, an exhibition gallery, shop and licensed bar. It is the only theatre in the Eastern region with a year-round programme of family-centred entertainment. Norwich Arts Centre theatre opened in 1977 in St Benedict's Street and has a capacity of 290. The Norwich Playhouse, which opened in 1995 and has a seating capacity of 300, is a venue in the heart of the city and one of the most modern performance spaces of its size in East Anglia.

The Garage studio theatre seats up to 110 in a range of layouts, or can be used for standing events for up to 180. Platform Theatre is in the grounds of the City College Norwich. Productions are staged mainly in the autumn and summer months. The theatre is raked and seats about 250. On 20 April 2012, it held a large relaunch event with an evening performance, showcasing it with previews of coming performances and scenes from past ones.[118]

The Whiffler Theatre, built in 1981, was given to the people of Norwich by the local newspaper group Eastern Daily Press. It is an open-air facility in Norwich Castle Gardens, with fixed-raked seating for up to 80 and standing for another 30 on the balcony. The stage is brick-built and has its dressing rooms set in a small building to stage left. The Whiffler mainly plays small Shakespeare productions. Sewell Barn Theatre is the smallest theatre in Norwich and has a seating capacity of just 100. The auditorium features raked seating on three sides of an open acting space. This staging helps to draw the audience closer into the performance.

Public performance spaces include the Forum in the city centre, with a large open-air amphitheatre for performances of many types throughout the year. Additionally, the cloisters of Norwich Cathedral are used for open-air performances as part of an annual Shakespeare festival.[119]

Museums

[edit]Norwich has several museums to reflect the history of the city and of Norfolk, and wider interests. The largest, Norwich Castle Museum, has extensive collections of archaeological finds from Norfolk, art (including a fine collection of paintings by the Norwich School of painters), ceramics (including the largest collection of British teapots), silver, and natural history. Of particular interest are dioramas of Norfolk scenery showing wildlife and landscape. It has been much remodelled to enhance the display of the collections and hosts frequent temporary exhibitions of art and other subjects.[120]

The Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell (until 2014 the Bridewell Museum) closed in 2010 for refurbishment of the building and overhaul of the displays,[121] and re-opened in July 2012.[122][123] The several galleries and groups of displays include "Life in Norwich: Our City 1900–1945"; "Life in Norwich: Our City 1945 Onwards"; and "England's Second City" depicting Norwich in the 18th century. "Made in Norwich", "Industrious City" and "Shoemakers" have exhibits connected with historic industries of Norwich, including weaving, shoe and bootmaking, iron foundries, and manufacture of metal goods, engineering, milling, brewing, chocolate-making and other food manufacturing. "Shopping and Trading" extends from the early 19th century to the 1960s.[124]

Strangers' Hall, at Charing Cross, is one of the oldest buildings in Norwich: a merchant's house from the early 14th century. The many rooms are furnished and equipped in the styles of different eras, from the Early Tudor to the Late Victorian. Exhibits include costumes and textiles, domestic objects, children's toys and games and children's books. The last two collections are seen to be of national importance.[125]

The Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum was, until 2011, housed in part of the former Shirehall, close to the castle. Although archives and the reserve collections are still held in the Shirehall, the principal museum display there closed in September 2011 and was relocated to the main Norwich Castle Museum, reopening fully in 2013.[126] It illustrates the history of the regiment from its 17th-century origins to its incorporation into the Royal Anglian Regiment in 1964, along with many aspects of its military life. There is an extensive, representative display of medals awarded to soldiers of the regiment, including two of the six Victoria Crosses won.[127][128]

The City of Norwich Aviation Museum is at Horsham St Faith, on the northern edge of the city, close to Norwich Airport. It has static displays of military and civil aircraft, with various collective exhibits, including one for the United States 8th Army Air Force.[129]

Formerly known as the John Jarrold Printing Museum, The Norwich Printing Museum covers the history of printing, with examples of printing machinery, presses, books and related equipment considered of national and international importance.[130] Exhibits date from the early 19th century to the present day. Some machinery and equipment are shown in use. Many items were donated by Jarrold Printing.[131] In November 2018, redevelopment plans for the museum site at Whitefriars caused uncertainty about its future.[132][133] The museum closed its Whitefriars premises on 23 October 2019, with a plan to relocate to the vacant medieval church of St Peter Parmentergate in King Street in 2020, but this site was later found to be unsuitable.[134][135] In 2021, the museum trustees were offered space at Blickling Hall, near Aylsham, and, as "The Norwich Printing Museum", it reopened there as a fully-working museum in July 2021.[136] Whilst the museum continues in its temporary home at Blickling, as at March 2023 the trustees were seeking permanent quarters in Norwich.[137] At October 2024, the search for a permanent home has continued, and the museum will be leaving its temporary home at Blickling in October 2025; by which time the trustees hope to have found a new home, preferably in Norwich.[138]

Dragon Hall in King Street exemplifies a medieval merchants' trading hall. Mostly dating from about 1430, it is unique in Western Europe. In 2006 the building underwent restoration. Its architecture is complemented by displays on the history of the building and its role in Norwich through the ages. The Norwich Castle Study Centre at the Shirehall in Market Avenue has some important collections, including one of more than 20,000 costume and textile items built up over some 130 years and previously kept in other Norwich museums. Although not a publicly open museum in the usual sense, items are accessible to the public, students and researchers by prior appointment.[139]

Entertainment

[edit]Norwich has three cinema complexes. Odeon Norwich is located in the Riverside Leisure Centre, Vue inside the Castle Mall and previously the Hollywood Cinema (closed 2019)[140] at Anglia Square, north of the city centre. Cinema City is an art-house cinema showing non-mainstream productions, operated by Picturehouse in St Andrews Street opposite St Andrew's Hall, whose patron was actor John Hurt.[141] Norwich has a large number of pubs throughout the city. Prince of Wales Road in the city centre, running from the Riverside district near Norwich railway station to Norwich Castle, is home to many of them, along with bars and clubs.

Media and film

[edit]

Norwich is the headquarters of BBC East, its presence in the East of England, and BBC Radio Norfolk, BBC Look East, Inside Out and The Politics Show are broadcast from studios in The Forum. Independent radio stations based in Norwich include Heart East, Smooth East Anglia, Greatest Hits Radio Norfolk and North Suffolk, and the University of East Anglia's Livewire 1350, an online station. A community station, Future Radio, was launched on 6 August 2007.

ITV Anglia, formerly Anglia Television, is based in Norwich. Although one of the smaller ITV companies, it supplied the network with some of its most popular shows such as Tales of the Unexpected, Survival and Sale of the Century (1971–1983), which began each edition with John Benson's enthusiastic announcement: "And now from Norwich, it's the quiz of the week!" The company also had a subsidiary called Anglia Multimedia, which produced educational content on CD and DVD mainly for schools, and was one of the three companies, along with Granada TV and the BBC vying for the right to produce a digital television station for English schools and colleges.

Launched in 1959, Anglia Television lost its independence in 1994 with a takeover by Meridian Broadcasting. Subsequent mergers have seen it reduced from a significant producer of programmes to a regional news centre. The company is still based in Anglia House, the former Norfolk and Norwich Agricultural Hall, on Agricultural Hall Plain near Prince of Wales Road.

Despite the contraction of Anglia, television production in Norwich has by no means ended. Anglia's former network production centre at Magdalen Street has been taken over by Norfolk County Council and revamped. After a total investment of £4 million from the East of England Development Agency (EEDA) it has re-opened as Epic Studios (East of England Production Innovation Centre). Degree courses in film and video are run at the centre by Norwich University of the Arts. Epic has commercial, broadcast-quality post-production facilities, a real-time virtual studio and a smaller HD discussion studio. The main studio opened as an HD facility in November 2008, when it began concentrating on the development of new TV formats and has worked on pilot shows.

Archant publishes two dailies in Norwich, the Norwich Evening News and the regional Eastern Daily Press (EDP). It had its own television operation, Mustard TV, which closed after being bought out by the That's TV group. Mustard TV is now That's Norfolk.

The character of Alan Partridge in the sitcom I'm Alan Partridge (1997–2002) and the comedy film Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa (2013) is a Norwich broadcaster played by Steve Coogan.

Esoteric associations

[edit]Because Norwich was England's second city in the medieval and Renaissance periods, it has some little acknowledged, but significant associations with esoteric spirituality. It was the home of William Cuningham, a physician who published An Invective Epistle in Defense of Astrologers in 1560.[142] The Elizabethan dramatist Robert Greene, author of Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, was born in Norwich in 1558. The city was the retirement residence of Arthur Dee (died Norwich, 1651), eldest son of the alchemist John Dee.[143][144]

Norwich was the residence of the physician and hermetic philosopher Sir Thomas Browne, author of The Garden of Cyrus (1658). Many influential esoteric titles are listed as once in Browne's library.[145] His coffin-plate, on display at the church of St Peter Mancroft, alludes to Paracelsian medicine and alchemy. Translated from Latin it reads, "Great Virtues, ...sleeping here the dust of his spagyric body converts the lead to gold." Browne was also a significant figure in the history of physiognomy.

The Church of St John Maddermarket's graveyard includes the Crabtree headstone, which has the pre-Christian symbol of the Ouroboros along with Masonic Square and Compasses carved upon it. Within the church is the Layer Monument, a rare example of an alchemical mandala in European funerary art.[146]

From 1787 the congregation of the New Jerusalem Church of Swedenborgians, followers of the mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, worshipped at the Church of St Mary the Less; in 1852 they moved to Park Lane, Norwich to establish the Swedenborgian Chapel.[147][148]

Architecture

[edit]Norwich's medieval period is represented by the 11th-century Norwich Cathedral, 12th-century castle (now a museum) and several parish churches, including the 15th-century Saint James the Less, Pockthorpe, which survived the bombing in World War II.[149] In the Middle Ages, 57 churches stood within the city wall; 31 still exist and seven are still used for worship.[150] There was a common regional saying that it had a church for every week of the year and a pub for every day. Norwich is said to have more standing medieval churches than any city north of the Alps.[94] The Adam and Eve is believed to be the oldest pub in the city,[151] with the earliest known reference made in 1249.[152] Most medieval buildings are in the city centre. Notable secular examples are Dragon Hall, built about 1430, and The Guildhall, built in 1407–1413 with later additions. From the 18th century, the pre-eminent local name is Thomas Ivory, who built the Assembly Rooms (1776), the Octagon Chapel (1756), St Helen's House (1752) in the grounds of the Great Hospital, and innovative speculative housing in Surrey Street (c. 1761). Ivory should not be confused with the Irish architect of the same name and a similar period.

The 19th century saw an explosion in Norwich's size and much of its housing stock, as well as commercial building in the city centre. The local architect of the Victorian and Edwardian periods who continues to command most respect was George Skipper (1856–1948). Examples of his work include the Norwich Union headquarters in Surrey Street the Modern Style (British Art Nouveau style) Royal Arcade, and the Hotel de Paris in the nearby seaside town of Cromer. The neo-Gothic Roman Catholic St John the Baptist Cathedral in Earlham Road was begun in 1882 by George Gilbert Scott Junior and his brother, John Oldrid Scott. George Skipper had great influence on the appearance of the city. John Betjeman compared it to Gaudi's influence on Barcelona.[153]

The city continued to grow through the 20th century. Much housing, particularly in areas further from the city centre, dates from that century. The first notable building since Skipper was the City Hall by C. H. James and S. R. Pierce, opened in 1938. At the same time they moved the City War Memorial, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, to a memorial garden between the city hall and the market place. Bombing during the Second World War, resulting in relatively little loss of life, caused marked damage to the housing stock in the city centre. Much of the post-war replacement stock was designed by the local-authority architect, David Percival. However, the major post-war architectural development in Norwich was the opening of the University of East Anglia in 1964. Originally designed by Denys Lasdun (his design was never completely executed), it has been added to over subsequent decades by major names such as Norman Foster and Rick Mather.

-

Norwich Cathedral lies close to Tombland in the city centre.

-

Elm Hill is an intact medieval street.

-

Cow Tower stands on the banks of the River Wensum.

-

The varying styles of architecture along Gentleman's Walk

Parks, gardens and open spaces

[edit]

See also List of parks, gardens and open spaces in Norwich

Chapelfield Gardens in central Norwich became the city's first public park in November 1880. From the start of the 20th century, Norwich Corporation began buying and leasing land to develop parks when funds became available. Sewell Park and James Stuart Gardens are examples of land donated by benefactors.

After the First World War the Corporation applied government grants to lay out a series of formal parks as a means to alleviate unemployment. Under Parks Superintendent Captain Sandys-Winsch,[154] Heigham Park was completed in 1924, Wensum Park in 1925, Eaton Park in 1928 and Waterloo Park in 1933. These retain many features from Sandys-Winsch's plans and have joined the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest.[155]

As of 2015, the city has 23 parks, 95 open spaces and 59 natural areas managed by the local authority.[156] In addition there are several private gardens occasionally opened to the public in aid of charity.[157] The Plantation Garden, also private, opens daily.[158]

Sport

[edit]

The principal local football club is Norwich City, known as the Canaries. In 2020–21 it finished first in the second tier of English football, the Championship, earning promotion to the Premier League for 2021–22. Majority-owned by celebrity chef Delia Smith and her husband Michael Wynn-Jones, its ground is Carrow Road Stadium. It has strong East Anglian rivalry with Ipswich Town. The club has enjoyed much success in the past, having played in the top division regularly since 1972, its longest spell being a nine-year run from 1986 to 1995. It has won two Football League Cups, and finished third in the inaugural Premier League in 1993. The club was relegated two years later and did not reclaim its place for nine years, going down again after just one season, only to return in 2011 after two successive promotions.

In 1993, the club eliminated German giants Bayern Munich from the UEFA Cup, in what is to date Norwich City's only season in European competitions; it had qualified for the UEFA Cup three times between 1985 and 1989 but been unable to compete as there was a ban on English clubs in European competitions at the time. Before emerging as a top division club, it famously eliminated Manchester United from the FA Cup in 1959 and went on to reach the semi-finals of the domestic cup competition, a run it achieved again in 1989 and most recently in 1992. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the club produced some highly-rated talent of that era, including striker Chris Sutton, winger Ruel Fox, defender Andy Linighan, midfielder Mike Phelan, midfielder Tim Sherwood and striker Justin Fashanu. The club's successful managers have included Ken Brown, Ron Saunders, Dave Stringer, Mike Walker, Nigel Worthington, Paul Lambert and Daniel Farke.[citation needed]

Norwich City Women play in the Women's National League Division One South East, the fourth tier of women's football.[159] They play their home games at The Nest and were formally integrated into Norwich City F.C. in 2022.[160] The original Norwich City Ladies won the Women's FA Cup in 1986, beating Doncaster Belles 4-3 in the final with Linda Curl, Miranda Colk, Sallie Jackson and Marianne Lawrence scoring the goals.[161]

The city's second men's club, Norwich United, is based in Blofield some 5 mi (8.0 km) east of the city. Along with Norwich CBS, it plays in the Eastern Counties League. The now-defunct Gothic was also based in Norwich. Local football clubs are served by the Norwich and District Saturday Football League.

Norwich has an athletics club, City of Norwich AC (CoNAC), a rugby club, the Norwich Lions, a handball Club, Norwich HC, and five field hockey clubs. In the 2012–2013 season, the club playing at the highest level on the men's side was Norwich City Hockey Club[162] in the East Hockey Premier B, which is two levels below the National League. The second highest is Norwich Dragons in Division Two North, then the students only University of East Anglia Men's Hockey Club in Division Three North East, then Norfolk Nomads Men's Hockey Club in Division Six North East. On the Ladies' side of the game, both Norwich City Hockey Club and Norwich Dragons Hockey club play in East Hockey's Division One North, two levels below National League. Following them, the students from the University of East Anglia Women's Hockey Club play in the Norfolk Premier Division. Also in Norwich, there is a veterans-only side, Norwich Exiles.[citation needed]

Since 2015, Norwich has hosted an annual 10k athletics road race, Run Norwich.

Outside the city boundary, the dry ski and snowboarding slopes of Norfolk Ski Club are located at Whitlingham Lane in Trowse. Close by in the parish of Whitlingham is Whitlingham Country Park,[163] home to the Outdoor Education Centre.[164] The centre is based on the south bank of the Great Broad which is also used by scuba divers from one of the city's three diving schools, and by other water and land sports.[165]

Of Norwich's two main rowing clubs, the Yare Boat Club is the older but smaller of the two. It is based on an island on the River Yare accessed from beside the Rivergarden pub in Thorpe Road. The larger Norwich Rowing Club, in partnership with Norwich Canoe Club, UEA Boat Club, Norwich School Boat Club and Norwich High School Rowing Club, has built a boathouse alongside Whitlingham Little Broad and the River Yare. Norwich Canoe Club[166] specialises in sprint and marathon racing. It holds the highest British Canoe Union Top Club Gold accreditation,[167] and is one of the more successful clubs in the UK. Ian Wynne, 2004 Olympics K1 500m bronze medallist, is an honorary member.

Speedway racing was staged in Norwich before and after World War II at The Firs Stadium in Holt Road, Hellesdon. The Norwich Stars raced in the Northern League of 1946 and the National League Division Two between 1947 and 1951, winning it in 1951. They were later elevated to the National League and raced at the top flight until the stadium was closed at the end of the 1964 season.[168] One meet was staged at a venue at Hevingham, but without an official permit, and it did not lead to a revival of the sport in the Norwich area.

In boxing, Norwich can boast former European and British lightweight champion Jon Thaxton,[169] reigning English light heavyweight champion Danny McIntosh[170] and heavyweight Sam Sexton, a former winner of the Prizefighter tournament.[171] Based in Norwich, Herbie Hide has been WBO Heavyweight World Champion twice, winning the championship in 1994–95 and for a second time in 1997.[172]

Norwich has a UK baseball team, the Norwich Iceni, which competes at the Single-A level of the BBF.[173] It was founded in 2015 with players from the UEA Blue Sox, who wished to carry on playing after university. The team officially joined the league in 2017 and was crowned BBF Single-A champions in its first season, going undefeated with 17 wins.[174]

Statistics

[edit]

Norwich was the second city of England after London for several centuries before industrialisation, which came late to Norwich due to its isolation and lack of raw materials.[citation needed]

In November 2006 the city was voted the greenest in the UK.[175] There is currently an initiative to make it a transition town. Norwich has been the scene of open discussions in public spaces, known as "meet in the street", to cover social and political issues.[176]

Articles in the past suggested that compared with other UK cities, Norwich was top of the league by percentage of population among who use the popular Internet auction site eBay.[177] The city also unveiled the then-biggest free Wi-Fi network in the UK in July 2006.[178]

In August 2007 Norwich was listed among nine finalists in its population group for the International Awards for Liveable Communities.[179] The city eventually won a silver award in the small-city category.

Economy and infrastructure

[edit]

Norwich's economy was historically manufacturing-based, including a large shoemaking industry, but it transitioned in the 1980s and 1990s into a service-based economy.[180]

The greater-Norwich economy (including Norwich, Broadland and South Norfolk government districts) as measured by GVA was estimated at £7.4 billion in 2011 (2011 GVA at 2006 prices).[181] The city's largest employment sectors are business and financial services (31%), public services (26%), retail (12%), manufacturing (8%) and tourism (7%).[182]

The proportion of working-age adults in Norwich claiming unemployment benefits is 3.3%[183] compared with 3.6% across the UK.[184]

New developments on the former Boulton and Paul site include a Riverside entertainment complex with nightclubs and other venues featuring the usual national leisure brands. Nearby, the football stadium is being upgraded with more residential property development alongside the River Wensum.

Archant, formerly Eastern Counties Newspapers (ECN), is a national publishing group that has grown out of the city's local newspapers and is headquartered in Norwich.

Norwich has long been associated with the making of mustard. The world-famous Colman's brand, with its yellow packaging, was founded in 1814 and operated from a factory at Carrow, latterly owned by Unilever. This site closed in 2019, with mustard now being made by Condimentum at Honingham, in a supply deal with Unilever.[185][186] Colman's is exported worldwide, putting Norwich on the map of British heritage brands. The Colman's Mustard Shop, which sold Colman's products and related gifts, was until 2017 located in the Royal Arcade in the centre of Norwich but closed in that year.[187]