Allopatric speciation

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

Allopatric speciation (from Ancient Greek ἄλλος (állos) 'other' and πατρίς (patrís) 'fatherland') – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model[1]: 86 – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from each other to an extent that prevents or interferes with gene flow.

Various geographic changes can arise such as the movement of continents, and the formation of mountains, islands, bodies of water, or glaciers. Human activity such as agriculture or developments can also change the distribution of species populations. These factors can substantially alter a region's geography, resulting in the separation of a species population into isolated subpopulations. The vicariant populations then undergo genetic changes as they become subjected to different selective pressures, experience genetic drift, and accumulate different mutations in the separated populations' gene pools. The barriers prevent the exchange of genetic information between the two populations leading to reproductive isolation. If the two populations come into contact they will be unable to reproduce—effectively speciating. Other isolating factors such as population dispersal leading to emigration can cause speciation (for instance, the dispersal and isolation of a species on an oceanic island) and is considered a special case of allopatric speciation called peripatric speciation.

Allopatric speciation is typically subdivided into two major models: vicariance and peripatric. These models differ from one another by virtue of their population sizes and geographic isolating mechanisms. The terms allopatry and vicariance are often used in biogeography to describe the relationship between organisms whose ranges do not significantly overlap but are immediately adjacent to each other—they do not occur together or only occur within a narrow zone of contact. Historically, the language used to refer to modes of speciation directly reflected biogeographical distributions.[2] As such, allopatry is a geographical distribution opposed to sympatry (speciation within the same area). Furthermore, the terms allopatric, vicariant, and geographical speciation are often used interchangeably in the scientific literature.[2] This article will follow a similar theme, with the exception of special cases such as peripatric, centrifugal, among others.

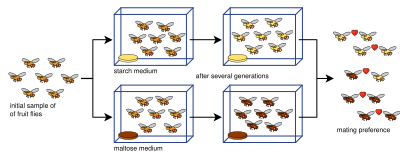

Observation of nature creates difficulties in witnessing allopatric speciation from "start-to-finish" as it operates as a dynamic process.[3] From this arises a host of issues in defining species, defining isolating barriers, measuring reproductive isolation, among others. Nevertheless, verbal and mathematical models, laboratory experiments, and empirical evidence overwhelmingly supports the occurrence of allopatric speciation in nature.[4][1]: 87–105 Mathematical modeling of the genetic basis of reproductive isolation supports the plausibility of allopatric speciation; whereas laboratory experiments of Drosophila and other animal and plant species have confirmed that reproductive isolation evolves as a byproduct of natural selection.[1]: 87

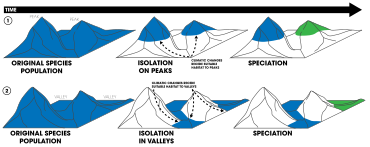

Vicariance model

[edit]

The notion of vicariant evolution was first developed by Léon Croizat in the mid-twentieth century.[5][6] The vicariance theory, which showed coherence along with the acceptance of plate tectonics in the 1960s, was developed in the early 1950s by this Venezuelan botanist, who had found an explanation for the similarity of plants and animals found in South America and Africa by deducing that they had originally been a single population before the two continents drifted apart.

Currently, speciation by vicariance is widely regarded as the most common form of speciation;[4] and is the primary model of allopatric speciation. Vicariance is a process by which the geographical range of an individual taxon, or a whole biota, is split into discontinuous populations (disjunct distributions) by the formation of an extrinsic barrier to the exchange of genes: that is, a barrier arising externally to a species. These extrinsic barriers often arise from various geologic-caused, topographic changes such as: the formation of mountains (orogeny); the formation of rivers or bodies of water; glaciation; the formation or elimination of land bridges; the movement of continents over time (by tectonic plates); or island formation, including sky islands. Vicariant barriers can change the distribution of species populations. Suitable or unsuitable habitat may be come into existence, expand, contract, or disappear as a result of global climate change or even large scale human activities (for example, agricultural, civil engineering developments, and habitat fragmentation). Such factors can alter a region's geography in substantial ways, resulting in the separation of a species population into isolated subpopulations. The vicariant populations may then undergo genotypic or phenotypic divergence as: (a) different mutations arise in the gene pools of the populations, (b) they become subjected to different selective pressures, and/or (c) they independently undergo genetic drift. The extrinsic barriers prevent the exchange of genetic information between the two populations, potentially leading to differentiation due to the ecologically different habitats they experience; selective pressure then invariably leads to complete reproductive isolation.[1]: 86 Furthermore, a species' proclivity to remain in its ecological niche (see phylogenetic niche conservatism) through changing environmental conditions may also play a role in isolating populations from one another, driving the evolution of new lineages.[7][8]

Allopatric speciation can be represented as the extreme on a gene flow continuum. As such, the level of gene flow between populations in allopatry would be , where equals the rate of gene exchange. In sympatry (panmixis), while in parapatric speciation, represents the entire continuum,[9] although some scientists argue[2][10] that a classification scheme based solely on geographic mode does not necessarily reflect the complexity of speciation.[11] Allopatry is often regarded as the default or "null" model of speciation,[2][12] but this too is debated.[13]

Reproductive isolation

[edit]Reproductive isolation acts as the primary mechanism driving genetic divergence in allopatry[14] and can be amplified by divergent selection.[15] Pre-zygotic and post-zygotic isolation are often the most cited mechanisms for allopatric speciation, and as such, it is difficult to determine which form evolved first in an allopatric speciation event.[14] Pre-zygotic simply implies the presence of a barrier prior to any act of fertilization (such as an environmental barrier dividing two populations), while post-zygotic implies the prevention of successful inter-population crossing after fertilization (such as the production of an infertile hybrid). Since species pairs who diverged in allopatry often exhibit pre- and post-zygotic isolation mechanisms, investigation of the earliest stages in the life cycle of the species can indicate whether or not divergence occurred due to a pre-zygotic or post-zygotic factor. However, establishing the specific mechanism may not be accurate, as a species pair continually diverges over time. For example, if a plant experiences a chromosome duplication event, reproduction will occur, but sterile hybrids will result—functioning as a form of post-zygotic isolation. Subsequently, the newly formed species pair may experience pre-zygotic barriers to reproduction as selection, acting on each species independently, will ultimately lead to genetic changes making hybrids impossible. From the researcher's perspective, the current isolating mechanism may not reflect the past isolating mechanism.[14]

Reinforcement

[edit]

Reinforcement has been a contentious factor in speciation.[16] It is more often invoked in sympatric speciation studies, as it requires gene flow between two populations. However, reinforcement may also play a role in allopatric speciation, whereby the reproductive barrier is removed, reuniting the two previously isolated populations. Upon secondary contact, individuals reproduce, creating low-fitness hybrids.[17] Traits of the hybrids drive individuals to discriminate in mate choice, by which pre-zygotic isolation increases between the populations.[11] Some arguments have been put forth that suggest the hybrids themselves can possibly become their own species:[18] known as hybrid speciation. Reinforcement can play a role in all geographic modes (and other non-geographic modes) of speciation as long as gene flow is present and viable hybrids can be formed. The production of inviable hybrids is a form of reproductive character displacement, under which most definitions is the completion of a speciation event.[11]

Research has well established the fact that interspecific mate discrimination occurs to a greater extent between sympatric populations than it does in purely allopatric populations; however, other factors have been proposed to account for the observed patterns.[19] Reinforcement in allopatry has been shown to occur in nature (evidence for speciation by reinforcement), albeit with less frequency than a classic allopatric speciation event.[14] A major difficulty arises when interpreting reinforcement's role in allopatric speciation, as current phylogenetic patterns may suggest past gene flow. This masks possible initial divergence in allopatry and can indicate a "mixed-mode" speciation event—exhibiting both allopatric and sympatric speciation processes.[13]

Mathematical models

[edit]Developed in the context of the genetic basis of reproductive isolation, mathematical scenarios model both prezygotic and postzygotic isolation with respect to the effects of genetic drift, selection, sexual selection, or various combinations of the three. Masatoshi Nei and colleagues were the first to develop a neutral, stochastic model of speciation by genetic drift alone. Both selection and drift can lead to postzygotic isolation, supporting the fact that two geographically separated populations can evolve reproductive isolation[1]: 87 —sometimes occurring rapidly.[20] Fisherian sexual selection can also lead to reproductive isolation if there are minor variations in selective pressures (such as predation risks or habitat differences) among each population.[21] (See the Further reading section below). Mathematical models concerning reproductive isolation-by distance have shown that populations can experience increasing reproductive isolation that correlates directly with physical, geographical distance.[22][23] This has been exemplified in models of ring species;[11] however, it has been argued that ring species are a special case, representing reproductive isolation-by distance, and demonstrate parapatric speciation instead[1]: 102 —as parapatric speciation represents speciation occurring along a cline.

Other models

[edit]Various alternative models have been developed concerning allopatric speciation. Special cases of vicariant speciation have been studied in great detail, one of which is peripatric speciation, whereby a small subset of a species population becomes isolated geographically; and centrifugal speciation, an alternative model of peripatric speciation concerning expansion and contraction of a species' range.[4] Other minor allopatric models have also been developed are discussed below.

Peripatric

[edit]

Peripatric speciation is a mode of speciation in which a new species is formed from an isolated peripheral population.[1]: 105 If a small population of a species becomes isolated (e.g. a population of birds on an oceanic island), selection can act on the population independent of the parent population. Given both geographic separation and enough time, speciation can result as a byproduct.[14] It can be distinguished from allopatric speciation by three important features: 1) the size of the isolated population, 2) the strong selection imposed by the dispersal and colonization into novel environments, and 3) the potential effects of genetic drift on small populations.[1]: 105 However, it can often be difficult for researchers to determine if peripatric speciation occurred as vicariant explanations can be invoked due to the fact that both models posit the absence of gene flow between the populations.[24] The size of the isolated population is important because individuals colonizing a new habitat likely contain only a small sample of the genetic variation of the original population. This promotes divergence due to strong selective pressures, leading to the rapid fixation of an allele within the descendant population. This gives rise to the potential for genetic incompatibilities to evolve. These incompatibilities cause reproductive isolation, giving rise to rapid speciation events.[1]: 105–106 Models of peripatry are supported mostly by species distribution patterns in nature. Oceanic islands and archipelagos provide the strongest empirical evidence that peripatric speciation occurs.[1]: 106–110

Centrifugal

[edit]Centrifugal speciation is a variant, alternative model of peripatric speciation. This model contrasts with peripatric speciation by virtue of the origin of the genetic novelty that leads to reproductive isolation.[25] When a population of a species experiences a period of geographic range expansion and contraction, it may leave small, fragmented, peripherally isolated populations behind. These isolated populations will contain samples of the genetic variation from the larger parent population. This variation leads to a higher likelihood of ecological niche specialization and the evolution of reproductive isolation.[4][26] Centrifugal speciation has been largely ignored in the scientific literature.[27][25][28] Nevertheless, a wealth of evidence has been put forth by researchers in support of the model, much of which has not yet been refuted.[4] One example is the possible center of origin in the Indo-West Pacific.[27]

Microallopatric

[edit]

Microallopatry refers to allopatric speciation occurring on a small geographic scale.[29] Examples of microallopatric speciation in nature have been described. Rico and Turner found intralacustrine allopatric divergence of Pseudotropheus callainos (Maylandia callainos) within Lake Malawi separated only by 35 meters.[30] Gustave Paulay found evidence that species in the subfamily Cryptorhynchinae have microallopatrically speciated on Rapa and its surrounding islets.[31] A sympatrically distributed triplet of diving beetle (Paroster) species living in aquifers of Australia's Yilgarn region have likely speciated microallopatrically within a 3.5 km2 area.[32] The term was originally proposed by Hobart M. Smith to describe a level of geographic resolution. A sympatric population may exist in low resolution, whereas viewed with a higher resolution (i.e. on a small, localized scale within the population) it is "microallopatric".[33] Ben Fitzpatrick and colleagues contend that this original definition, "is misleading because it confuses geographical and ecological concepts".[29]

Modes with secondary contact

[edit]Ecological speciation can occur allopatrically, sympatrically, or parapatrically; the only requirement being that it occurs as a result of adaptation to different ecological or micro-ecological conditions.[34] Ecological allopatry is a reverse-ordered form of allopatric speciation in conjunction with reinforcement.[13] First, divergent selection separates a non-allopatric population emerging from pre-zygotic barriers, from which genetic differences evolve due to the obstruction of complete gene flow.[35] The terms allo-parapatric and allo-sympatric have been used to describe speciation scenarios where divergence occurs in allopatry but speciation occurs only upon secondary contact.[1]: 112 These are effectively models of reinforcement[36] or "mixed-mode" speciation events.[13]

Observational evidence

[edit]As allopatric speciation is widely accepted as a common mode of speciation, the scientific literature is abundant with studies documenting its existence. The biologist Ernst Mayr was the first to summarize the contemporary literature of the time in 1942 and 1963.[1]: 91 Many of the examples he set forth remain conclusive; however, modern research supports geographic speciation with molecular phylogenetics[37]—adding a level of robustness unavailable to early researchers.[1]: 91 The most recent thorough treatment of allopatric speciation (and speciation research in general) is Jerry Coyne and H. Allen Orr's 2004 publication Speciation. They list six mainstream arguments that lend support to the concept of vicariant speciation:

- Closely related species pairs, more often than not, reside in geographic ranges adjacent to one another, separated by a geographic or climatic barrier.

- Young species pairs (or sister species) often occur in allopatry, even without a known barrier.

- In occurrences where several pairs of related species share a range, they are distributed in abutting patterns, with borders exhibiting zones of hybridization.

- In regions where geographic isolation is doubtful, species do not exhibit sister pairs.

- Correlation of genetic differences between an array of distantly related species that correspond to known current or historical geographic barriers.

- Measures of reproductive isolation increase with the greater geographic distance of separation between two species pairs. (This has been often referred to as reproductive isolation by distance.[11])

Endemism

[edit]Allopatric speciation has resulted in many of the biogeographic and biodiversity patterns found on Earth: on islands,[38] continents,[39] and even among mountains.[40]

Islands are often home to species endemics—existing only on an island and nowhere else in the world—with nearly all taxa residing on isolated islands sharing common ancestry with a species on the nearest continent.[41] Not without challenge, there is typically a correlation between island endemics and diversity;[42] that is, that the greater the diversity (species richness) of an island, the greater the increase in endemism.[43] Increased diversity effectively drives speciation.[44] Furthermore, the number of endemics on an island is directly correlated with the relative isolation of the island and its area.[45] In some cases, speciation on islands has occurred rapidly.[46]

Dispersal and in situ speciation are the agents that explain the origins of the organisms in Hawaii.[47] Various geographic modes of speciation have been studied extensively in Hawaiian biota, and in particular, angiosperms appear to have speciated predominately in allopatric and parapatric modes.[47]

Islands are not the only geographic locations that have endemic species. South America has been studied extensively with its areas of endemism representing assemblages of allopatrically distributed species groups. Charis butterflies are a primary example, confined to specific regions corresponding to phylogenies of other species of butterflies, amphibians, birds, marsupials, primates, reptiles, and rodents.[48] The pattern indicates repeated vicariant speciation events among these groups.[48] It is thought that rivers may play a role as the geographic barriers to Charis,[1]: 97 not unlike the river barrier hypothesis used to explain the high rates of diversity in the Amazon basin—though this hypothesis has been disputed.[49][50] Dispersal-mediated allopatric speciation is also thought to be a significant driver of diversification throughout the Neotropics.[51]

Patterns of increased endemism at higher elevations on both islands and continents have been documented on a global level.[40] As topographical elevation increases, species become isolated from one another;[52] often constricted to graded zones.[40] This isolation on "mountain top islands" creates barriers to gene flow, encouraging allopatric speciation, and generating the formation of endemic species.[40] Mountain building (orogeny) is directly correlated with—and directly affects biodiversity.[53][54] The formation of the Himalayan mountains and the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau for example have driven the speciation and diversification of numerous plants and animals[55] such as Lepisorus ferns;[56] glyptosternoid fishes (Sisoridae);[57] and the Rana chensinensis species complex.[58] Uplift has also driven vicariant speciation in Macowania daisies in South Africa's Drakensberg mountains,[59] along with Dendrocincla woodcreepers in the South American Andes.[60] The Laramide orogeny during the Late Cretaceous even caused vicariant speciation and radiations of dinosaurs in North America.[61]

Adaptive radiation, like the Galapagos finches observed by Charles Darwin, is often a consequence of rapid allopatric speciation among populations. However, in the case of the finches of the Galapagos, among other island radiations such as the honeycreepers of Hawaii represent cases of limited geographic separation and were likely driven by ecological speciation.

Isthmus of Panama

[edit]

Geological evidence supports the final closure of the isthmus of Panama approximately 2.7 to 3.5 mya,[62] with some evidence suggesting an earlier transient bridge existing between 13 and 15 mya.[63] Recent evidence increasingly points towards an older and more complex emergence of the Isthmus, with fossil and extant species dispersal (part of the American biotic interchange) occurring in three major pulses, to and from North and South America.[64] Further, the changes in terrestrial biotic distributions of both continents such as with Eciton army ants supports an earlier bridge or a series of bridges.[65][66] Regardless of the exact timing of the isthmus closer, biologists can study the species on the Pacific and Caribbean sides in what has been called, "one of the greatest natural experiments in evolution".[62] Additionally, as with most geologic events, the closure was unlikely to have occurred rapidly, but instead dynamically—a gradual shallowing of sea water over millions of years.[1]: 93

Studies of snapping shrimp in the genus Alpheus have provided direct evidence of an allopatric speciation event,[67] as phylogenetic reconstructions support the relationships of 15 pairs of sister species of Alpheus, each pair divided across the isthmus[62] and molecular clock dating supports their separation between 3 and 15 million years ago.[68] Recently diverged species live in shallow mangrove waters[68] while older diverged species live in deeper water, correlating with a gradual closure of the isthmus.[1]: 93 Support for an allopatric divergence also comes from laboratory experiments on the species pairs showing nearly complete reproductive isolation.[1]: 93

Similar patterns of relatedness and distribution across the Pacific and Atlantic sides have been found in other species pairs such as:[69]

- Diadema antillarum and Diadema mexicanum

- Echinometra lucunter and Echinometra vanbrunti

- Echinometra viridis and E. vanbrunti

- Bathygobius soporator and Bathygobius ramosus

- B. soporator and Bathygobius andrei

- Excirolana braziliensis and variant morphs

Refugia

[edit]Ice ages have played important roles in facilitating speciation among vertebrate species.[70] This concept of refugia has been applied to numerous groups of species and their biogeographic distributions.[1]: 97

Glaciation and subsequent retreat caused speciation in many boreal forest birds,[70] such as with North American sapsuckers (Yellow-bellied, Red-naped, and Red-breasted); the warblers in the genus Setophaga (S. townsendii, S. occidentalis, and S. virens), Oreothlypis (O. virginiae, O. ridgwayi, and O. ruficapilla), and Oporornis (O. tolmiei and O. philadelphia now classified in the genus Geothlypis); Fox sparrows (sub species P. (i.) unalaschensis, P. (i.) megarhyncha, and P. (i.) schistacea); Vireo (V. plumbeus, V. cassinii, and V. solitarius); tyrant flycatchers (E. occidentalis and E. difficilis); chickadees (P. rufescens and P. hudsonicus); and thrushes (C. bicknelli and C. minimus).[70]

As a special case of allopatric speciation, peripatric speciation is often invoked for instances of isolation in glaciation refugia as small populations become isolated due to habitat fragmentation such as with North American red (Picea rubens) and black (Picea mariana) spruce[71] or the prairie dogs Cynomys mexicanus and C. ludovicianus.[72]

Superspecies

[edit]

Numerous species pairs or species groups show abutting distribution patterns, that is, reside in geographically distinct regions next to each other. They often share borders, many of which contain hybrid zones. Some examples of abutting species and superspecies (an informal rank referring to a complex of closely related allopatrically distributed species, also called allospecies[73]) include:

- Western and Eastern meadowlarks in North America reside in dry western and wet eastern geographic regions with rare occurrences of hybridization, most of which results in infertile offspring.[41]

- Monarch flycatchers endemic to the Solomon Islands; a complex of several species and subspecies (Bougainville, white-capped, and chestnut-bellied monarchs and their related subspecies).[41]

- North American sapsuckers and members of the genus Setophaga (the hermit warbler, black-throated green warbler, and Townsend's warbler).[41][70]

- Sixty-six subspecies in the genus Pachycephala residing on the Melanesian islands.[41][74]

- Bonobos and chimpanzees.

- Climacteris tree creeper birds in Australia.[75]

- Birds-of-paradise in the mountains of New Guinea (genus Astrapia).[75]

- Red-shafted and yellow-shafted flickers; black-headed grosbeaks and rose-breasted grosbeaks; Baltimore orioles and Bullock's orioles; and the lazuli and indigo buntings.[76] All of these species pairs connect at zones of hybridization that correspond with major geographic barriers.[1]: 97–99

- Dugesia flatworms in Europe, Asia, and the Mediterranean regions.[75]

- Dichromatic toucanets of the genus Selenidera may be a superspecies that arose by the refugia hypothesis in the Amazon basin.[77]

In birds, some areas are prone to high rates of superspecies formation such as the 105 superspecies in Melanesia, comprising 66 percent of all bird species in the region.[78] Patagonia is home to 17 superspecies of forest birds,[79] while North America has 127 superspecies of both land and freshwater birds.[80] Sub-Saharan Africa has 486 passerine birds grouped into 169 superspecies.[81] Australia has numerous bird superspecies as well, with 34 percent of all bird species grouped into superspecies.[41]

Laboratory evidence

[edit]

Experiments on allopatric speciation are often complex and do not simply divide a species population into two. This is due to a host of defining parameters: measuring reproductive isolation, sample sizes (the number of matings conducted in reproductive isolation tests), bottlenecks, length of experiments, number of generations allowed,[84] or insufficient genetic diversity.[85] Various isolation indices have been developed to measure reproductive isolation (and are often employed in laboratory speciation studies) such as here (index [86] and index [87]):

Here, and represent the number of matings in heterogameticity where and represent homogametic matings. and is one population and and is the second population. A negative value of denotes negative assortive mating, a positive value denotes positive assortive mating (i. e. expressing reproductive isolation), and a null value (of zero) means the populations are experiencing random mating.[84]

The experimental evidence has solidly established the fact that reproductive isolation evolves as a by-product of selection.[15][1]: 90 Reproductive isolation has been shown to arise from pleiotropy (i.e. indirect selection acting on genes that code for more than one trait)—what has been referred to as genetic hitchhiking.[15] Limitations and controversies exist relating to whether laboratory experiments can accurately reflect the long-scale process of allopatric speciation that occurs in nature. Experiments often fall beneath 100 generations, far less than expected, as rates of speciation in nature are thought to be much larger.[1]: 87 Furthermore, rates specifically concerning the evolution of reproductive isolation in Drosophila are significantly higher than what is practiced in laboratory settings.[88] Using index Y presented previously, a survey of 25 allopatric speciation experiments (included in the table below) found that reproductive isolation was not as strong as typically maintained and that laboratory environments have not been well-suited for modeling allopatric speciation.[84] Nevertheless, numerous experiments have shown pre-zygotic and post-zygotic isolation in vicariance, some in less than 100 generations.[1]: 87

Below is a non-exhaustive table of the laboratory experiments conducted on allopatric speciation. The first column indicates the species used in the referenced study, where the "Trait" column refers to the specific characteristic selected for or against in that species. The "Generations" column refers to the number of generations in each experiment performed. If more than one experiment was formed generations are separated by semicolons or dashes (given as a range). Some studies provide a duration in which the experiment was conducted. The "Selection type" column indicates if the study modeled vicariant or peripatric speciation (this may not be explicitly). Direct selection refers to selection imposed to promote reproductive isolation whereas indirect selection implies isolation occurring as a pleiotropic byproduct of natural selection; whereas divergent selection implies deliberate selection of each allopatric population in opposite directions (e.g. one line with more bristles and the other line with less). Some studies performed experiments modeling or controlling for genetic drift. Reproductive isolation occurred pre-zygotically, post-zygotically, both, or not at all. It is important to note that many of the studies conducted contain multiple experiments within—a resolution of which this table does not reflect.

| Species | Trait | ~Generations (duration) | Selection type | Studied Drift | Reproductive isolation | Year & Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila melanogaster |

Escape response | 18 | Indirect; divergent | Yes | Pre-zygotic | 1969[89] |

| Locomotion | 112 | Indirect; divergent | No | Pre-zygotic | 1974[90] | |

| Temperature, humidity | 70–130 | Indirect; divergent | Yes | Pre-zygotic | 1980[91] | |

| DDT adaptation | 600 (25 years, +15 years) | Direct | No | Pre-zygotic | 2003[92] | |

| 17, 9, 9, 1, 1, 7, 7, 7, 7 | Direct, divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1974[93] | |||

| 40; 50 | Direct; divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1974[94] | |||

| Locomotion | 45 | Direct; divergent | No | None | 1979[95][96] | |

| Direct; divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1953[97] | ||||

| 36; 31 | Direct; divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1956[98] | |||

| EDTA adaptation | 3 experiments, 25 each | Indirect | No | Post-zygotic | 1966[99][100] | |

| 8 experiments, 25 each | Direct | 1997[101] | ||||

| Abdominal chaeta

number |

21–31 | Direct | Yes | None | 1958[102] | |

| Sternopleural chaeta number | 32 | Direct | No | None | 1969[103] | |

| Phototaxis, geotaxis | 20 | No | None | 1975[104] 1981[105] | ||

| Yes | 1998[106] | |||||

| Yes | 1999[107] | |||||

| Direct; divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1971[108] 1973[109] 1979[110] 1983[111] | ||||

| D. simulans | Scutellar bristles, development speed, wing width;

desiccation resistance, fecundity, ethanol resistance; courtship display, re-mating speed, lek behavior; pupation height, clumped egg laying, general activity |

3 years | Yes | Post-zygotic | 1985[112] | |

| D. paulistorum | 131; 131 | Direct | Pre-zygotic | 1976[113] | ||

| 5 years | 1966[114] | |||||

| D. willistoni | pH adaptation | 34–122 | Indirect; divergent | No | Pre-zygotic | 1980[115] |

| D. pseudoobscura | Carbohydrate source | 12 | Indirect | Yes | Pre-zygotic | 1989[83] |

| Temperature adaptation | 25–60 | Direct | 1964[116] 1969[117] | |||

| Phototaxis, geotaxis | 5–11 | Indirect | No | Pre-zygotic | 1966[118] | |

| Pre-zygotic | 1978[119] 1985[120] | |||||

| Yes | 1993[121] | |||||

| Temperature photoperiod; food | 37 | Divergent | Yes | None | 2003[122] | |

| D.pseudoobscura & | 22; 16; 9 | Direct; divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1950[123] | ||

| 4 experiments, 18 each | Direct | Pre-zygotic | 1966[124] | |||

| D. mojavensis | 12 | Direct | Pre-zygotic | 1987[125] | ||

| Development time | 13 | Divergent | Yes | None | 1998[126] | |

| D. adiastola | Yes | Pre-zygotic | 1974[127] | |||

| D. silvestris | Yes | 1980[128] | ||||

| Musca domestica | Geotaxis | 38 | Indirect | No | Pre-zygotic | 1974[129] |

| Geotaxis | 16 | Direct; divergent | No | Pre-zygotic | 1975[130] | |

| Yes | 1991[131] | |||||

| Bactrocera cucurbitae | Development time | 40–51 | Divergent | Yes | Pre-zygotic | 1999[132] |

| Zea mays | 6; 6 | Direct; divergent | Pre-zygotic | 1969[133] | ||

| D. grimshawi | [134] |

History and research techniques

[edit]Early speciation research typically reflected geographic distributions and were thus termed geographic, semi-geographic, and non-geographic.[2] Geographic speciation corresponds to today's usage of the term allopatric speciation, and in 1868, Moritz Wagner was the first to propose the concept[135] of which he used the term Separationstheorie.[136] His idea was later interpreted by Ernst Mayr as a form of founder effect speciation as it focused primarily on small geographically isolated populations.[136]

Edward Bagnall Poulton, an evolutionary biologist and a strong proponent of the importance of natural selection, highlighted the role of geographic isolation in promoting speciation,[11] in the process coining the term "sympatric speciation" in 1903.[137]

Controversy exists as to whether Charles Darwin recognized a true geographical-based model of speciation in his publication of the Origin of Species.[136] In chapter 11, "Geographical Distribution", Darwin discusses geographic barriers to migration, stating for example that "barriers of any kind, or obstacles to free migration, are related in a close and important manner to the differences between the productions of various regions [of the world]".[138] F. J. Sulloway contends that Darwin's position on speciation was "misleading" at the least[139] and may have later misinformed Wagner and David Starr Jordan into believing that Darwin viewed sympatric speciation as the most important mode of speciation.[1]: 83 Nevertheless, Darwin never fully accepted Wagner's concept of geographical speciation.[136]

David Starr Jordan played a significant role in promoting allopatric speciation in the early 20th century, providing a wealth of evidence from nature to support the theory.[1]: 86 [135][140] Much later, the biologist Ernst Mayr was the first to encapsulate the then contemporary literature in his 1942 publication Systematics and the Origin of Species, from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist and in his subsequent 1963 publication Animal Species and Evolution. Like Jordan's works, they relied on direct observations of nature, documenting the occurrence of allopatric speciation, of which is widely accepted today.[1]: 83–84 Prior to this research, Theodosius Dobzhansky published Genetics and the Origin of Species in 1937 where he formulated the genetic framework for how speciation could occur.[1]: 2

Other scientists noted the existence of allopatrically distributed pairs of species in nature such as Joel Asaph Allen (who coined the term "Jordan's Law", whereby closely related, geographically isolated species are often found divided by a physical barrier[1]: 91 ) and Robert Greenleaf Leavitt;[141] however, it is thought that Wagner, Karl Jordan, and David Starr Jordan played a large role in the formation of allopatric speciation as an evolutionary concept;[142] where Mayr and Dobzhansky contributed to the formation of the modern evolutionary synthesis.

The late 20th century saw the development of mathematical models of allopatric speciation, leading to the clear theoretical plausibility that geographic isolation can result in the reproductive isolation of two populations.[1]: 87

Since the 1940s, allopatric speciation has been accepted.[143] Today, it is widely regarded as the most common form of speciation taking place in nature.[1]: 84 However, this is not without controversy, as both parapatric and sympatric speciation are both considered tenable modes of speciation that occur in nature.[143] Some researchers even consider there to be a bias in reporting of positive allopatric speciation events, and in one study reviewing 73 speciation papers published in 2009, only 30 percent that suggested allopatric speciation as the primary explanation for the patterns observed considered other modes of speciation as possible.[13]

Contemporary research relies largely on multiple lines of evidence to determine the mode of a speciation event; that is, determining patterns of geographic distribution in conjunction with phylogenetic relatedness based on molecular techniques.[1]: 123–124 This method was effectively introduced by John D. Lynch in 1986 and numerous researchers have employed it and similar methods, yielding enlightening results.[144] Correlation of geographic distribution with phylogenetic data also spawned a sub-field of biogeography called vicariance biogeography[1]: 92 developed by Joel Cracraft, James Brown, Mark V. Lomolino, among other biologists specializing in ecology and biogeography. Similarly, full analytical approaches have been proposed and applied to determine which speciation mode a species underwent in the past using various approaches or combinations thereof: species-level phylogenies, range overlaps, symmetry in range sizes between sister species pairs, and species movements within geographic ranges.[37] Molecular clock dating methods are also often employed to accurately gauge divergence times that reflect the fossil or geological record[1]: 93 (such as with the snapping shrimp separated by the closure of the Isthmus of Panama[68] or speciation events within the genus Cyclamen[145]). Other techniques used today have employed measures of gene flow between populations,[13] ecological niche modelling (such as in the case of the Myrtle and Audubon's warblers[146] or the environmentally-mediated speciation taking place among dendrobatid frogs in Ecuador[144]), and statistical testing of monophyletic groups.[147] Biotechnological advances have allowed for large scale, multi-locus genome comparisons (such as with the possible allopatric speciation event that occurred between ancestral humans and chimpanzees[148]), linking species' evolutionary history with ecology and clarifying phylogenetic patterns.[149]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Coyne, Jerry A.; Orr, H. Allen (2004). Speciation. Sinauer Associates. pp. 1–545. ISBN 978-0-87893-091-3.

- ^ a b c d e Richard G. Harrison (2012), "The Language of Speciation", Evolution, 66 (12): 3643–3657, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01785.x, PMID 23206125, S2CID 31893065

- ^ Ernst Mayr (1970), Populations, Species, and Evolution: An Abridgment of Animal Species and Evolution, Harvard University Press, p. 279, ISBN 978-0674690134

- ^ a b c d e Howard, Daniel J. (2003). "Speciation: Allopatric". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001748. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ Croizat L (1958).Panbiogeography or An Introductory Synthesis of Zoogeography, Phytogeography, Geology; with notes on evolution, systematics, ecology, anthropology, etc.. Caracas: Published by the author, 2755 pp.

- ^ Croizat L (1964). Space, Time, Form: The Biological Synthesis. Caracas: Published by the author. p. 676.

- ^ John J. Wiens (2004), "Speciation and Ecology Revisited: Phylogenetic Niche Conservatism and the Origin of Species", Evolution, 58 (1): 193–197, doi:10.1554/03-447, PMID 15058732, S2CID 198159058

- ^ John J. Wiens; Catherine H. Graham (2005), "Niche Conservatism: Integrating Evolution, Ecology, and Conservation Biology", Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 36: 519–539, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102803.095431, S2CID 3895737

- ^ Sergey Gavrilets (2004), Fitness landscapes and the origin of species, Princeton University Press, p. 13

- ^ Sara Via (2001), "Sympatric speciation in animals: the ugly duckling grows up", Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16 (1): 381–390, doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02188-7, PMID 11403871

- ^ a b c d e f Hannes Schuler; Glen R. Hood; Scott P. Egan; Jeffrey L. Feder (2016), "Modes and Mechanisms of Speciation", Reviews in Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, 2 (3): 60–93, doi:10.1002/3527600906

- ^ Kerstin Johannesson (2009), "Inverting the null-hypothesis of speciation: a marine snail perspective", Evolutionary Ecology, 23 (1): 5–16, Bibcode:2009EvEco..23....5J, doi:10.1007/s10682-007-9225-1, S2CID 23644576

- ^ a b c d e f Kerstin Johannesson (2010), "Are we analyzing speciation without prejudice?", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1206 (1): 143–149, Bibcode:2010NYASA1206..143J, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05701.x, PMID 20860687, S2CID 41791817

- ^ a b c d e Michael Turelli; Nicholas H. Barton; Jerry A. Coyne (2001), "Theory and speciation", Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16 (7): 330–343, doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02177-2, PMID 11403865

- ^ a b c d William R. Rice; Ellen E. Hostert (1993), "Laboratory Experiments on Speciation: What Have We Learned in 40 Years?", Evolution, 47 (6): 1637–1653, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01257.x, JSTOR 2410209, PMID 28568007, S2CID 42100751

- ^ Hvala, John A.; Wood, Troy E. (2012). Speciation: Introduction. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0001709.pub3. ISBN 978-0470016176.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Conrad J. Hoskin; Megan Higgie; Keith R. McDonald; Craig Moritz (2005), "Reinforcement drives rapid allopatric speciation", Nature, 437 (7063): 1353–1356, Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1353H, doi:10.1038/nature04004, PMID 16251964, S2CID 4417281

- ^ Arnold, M.L. (1996). Natural Hybridization and Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-19-509975-1.

- ^ Mohamed A. F. Noor (1999), "Reinforcement and other consequences of sympatry", Heredity, 83 (5): 503–508, doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6886320, PMID 10620021

- ^ Christopher J. Wills (1977), "A Mechanism for Rapid Allopatric Speciation", The American Naturalist, 111 (979): 603–605, Bibcode:1977ANat..111..603W, doi:10.1086/283191, S2CID 84293637

- ^ Andrew Pomiankowski and Yoh Iwasa (1998), "Runaway ornament diversity caused by Fisherian sexual selection", PNAS, 95 (9): 5106–5111, Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.5106P, doi:10.1073/pnas.95.9.5106, PMC 20221, PMID 9560236

- ^ Sewall Wright (1943), "Isolation by distance", Genetics, 28 (2): 114–138, doi:10.1093/genetics/28.2.114, PMC 1209196, PMID 17247074

- ^ Montgomery Slatkin (1993), "Isolation by distance in equilibrium and non-equilibrium populations", Evolution, 47 (1): 264–279, doi:10.2307/2410134, JSTOR 2410134, PMID 28568097

- ^ Lucinda P. Lawson; et al. (2015), "Divergence at the edges: peripatric isolation in the montane spiny throated reed frog complex", BMC Evolutionary Biology, 15 (128): 128, Bibcode:2015BMCEE..15..128L, doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0384-3, PMC 4487588, PMID 26126573

- ^ a b Sergey Gavrilets; et al. (2000), "Patterns of Parapatric Speciation", Evolution, 54 (4): 1126–1134, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.42.6514, doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2000)054[1126:pops]2.0.co;2, PMID 11005282, S2CID 198153997

- ^ W. L. Brown Jr. (1957), "Centrifugal speciation", Quarterly Review of Biology, 32 (3): 247–277, doi:10.1086/401875, S2CID 225071133

- ^ a b John C. Briggs (2000), "Centrifugal speciation and centres of origin", Journal of Biogeography, 27 (5): 1183–1188, Bibcode:2000JBiog..27.1183B, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00459.x, S2CID 86734208

- ^ Jennifer K. Frey (1993), "Modes of Peripheral Isolate Formation and Speciation", Systematic Biology, 42 (3): 373–381, doi:10.1093/sysbio/42.3.373, S2CID 32546573

- ^ a b B. M. Fitzpatrick; A. A. Fordyce; S. Gavrilets (2008), "What, if anything, is sympatric speciation?", Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21 (6): 1452–1459, doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01611.x, PMID 18823452, S2CID 8721116

- ^ C. Rico; G. F. Turner (2002), "Extreme microallopatric divergence in a cichlid species from Lake Malawi", Molecular Ecology, 11 (8): 1585–1590, Bibcode:2002MolEc..11.1585R, doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01537.x, hdl:10261/59425, PMID 12144678, S2CID 16543963

- ^ Gustav Paulay (1985), "Adaptive radiation on an isolated oceanic island: the Cryptorhynchinae (Curculionidae)of Rapa revisited", Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 26 (2): 95–187, doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1985.tb01554.x

- ^ M. T. Guzik; S. J. B. Cooper; W. F. Humphreys; A. D. Austin (2009), "Fine-scale comparative phylogeography of a sympatric sister species triplet of subterranean diving beetles from a single calcrete aquifer in Western Australia", Molecular Ecology, 18 (17): 3683–3698, Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.3683G, doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04296.x, PMID 19674311, S2CID 25821896

- ^ Hobart M. Smith (1965), "More Evolutionary Terms", Systematic Biology, 14 (1): 57–58, doi:10.2307/2411904, JSTOR 2411904

- ^ Nosil, P. (2012). Ecological Speciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0199587117.

- ^ Sara Via (2009), "Natural selection in action during speciation", PNAS, 106 (Suppl 1): 9939–9946, Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9939V, doi:10.1073/pnas.0901397106, PMC 2702801, PMID 19528641

- ^ Guy L. Bush (1994), "Sympatric speciation in animals: new wine in old bottles", Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 9 (8): 285–288, Bibcode:1994TEcoE...9..285B, doi:10.1016/0169-5347(94)90031-0, PMID 21236856

- ^ a b Timothy G. Barraclough; Alfried P. Vogler (2000), "Detecting the Geographical Pattern of Speciation from Species-Level Phylogenies", American Naturalist, 155 (4): 419–434, doi:10.2307/3078926, JSTOR 3078926, PMID 10753072

- ^ Robert J. Whittaker; José María Fernández-Palacios (2007), Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation (2 ed.), Oxford University Press

- ^ Hong Qian; Robert E. Ricklefs (2000), "Large-scale processes and the Asian bias in species diversity of temperate plants", Nature, 407 (6801): 180–182, Bibcode:2000Natur.407..180Q, doi:10.1038/35025052, PMID 11001054, S2CID 4416820

- ^ a b c d Manuel J. Steinbauer; Richard Field; John-Arvid Grytnes; Panayiotis Trigas; Claudine Ah-Peng; Fabio Attorre; H. John B. Birks; Paulo A. V. Borges; Pedro Cardoso; Chang-Hung Chou; Michele De Sanctis; Miguel M. de Sequeira; Maria C. Duarte; Rui B. Elias; José María Fernández-Palacios; Rosalina Gabriel; Roy E. Gereau; Rosemary G. Gillespie; Josef Greimler; David E. V. Harter; Tsurng-Juhn Huang; Severin D. H. Irl; Daniel Jeanmonod; Anke Jentsch; Alistair S. Jump; Christoph Kueffer; Sandra Nogué; Rüdiger Otto; Jonathan Price; Maria M. Romeiras; Dominique Strasberg; Tod Stuessy; Jens-Christian Svenning; Ole R. Vetaas; Carl Beierkuhnlein (2016), "Topography-driven isolation, speciation and a global increase of endemism with elevation" (PDF), Global Ecology and Biogeography, 25 (9): 1097–1107, Bibcode:2016GloEB..25.1097S, doi:10.1111/geb.12469, hdl:1893/23221

- ^ a b c d e f Trevor Price (2008), Speciation in Birds, Roberts and Company Publishers, pp. 1–64, ISBN 978-0-9747077-8-5

- ^ Xiao-Yong Chen; Fangliang He (2009), "Speciation and Endemism under the Model of Island Biogeography", Ecology, 90 (1): 39–45, Bibcode:2009Ecol...90...39C, doi:10.1890/08-1520.1, PMID 19294911, S2CID 24127933

- ^ Carlos Daniel Cadena; Robert E. Ricklefs; Iván Jiménez; Eldredge Bermingham (2005), "Ecology: Is speciation driven by species diversity?", Nature, 438 (7064): E1–E2, Bibcode:2005Natur.438E...1C, doi:10.1038/nature04308, PMID 16267504, S2CID 4418564

- ^ Brent C. Emerson; Niclas Kolm (2005), "Species diversity can drive speciation", Nature, 434 (7036): 1015–1017, Bibcode:2005Natur.434.1015E, doi:10.1038/nature03450, PMID 15846345, S2CID 3195603

- ^ Trevor Price (2008), Speciation in Birds, Roberts and Company Publishers, pp. 141–155, ISBN 978-0-9747077-8-5

- ^ Jonathan B. Losos; Dolph Schluter (2000), "Analysis of an evolutionary species±area relationship", Nature, 408 (6814): 847–850, Bibcode:2000Natur.408..847L, doi:10.1038/35048558, PMID 11130721, S2CID 4400514

- ^ a b Jonathan P. Price; Warren L. Wagner (2004), "Speciation in Hawaiian Angiosperm Lineages: Cause, Consequence, and Mode", Evolution, 58 (10): 2185–2200, doi:10.1554/03-498, PMID 15562684, S2CID 198157925

- ^ a b Jason P. W. Hall; Donald J. Harvey (2002), "The Phylogeography of Amazonia Revisited: New Evidence from Riodinid Butterflies", Evolution, 56 (7): 1489–1497, doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[1489:tpoarn]2.0.co;2, PMID 12206248, S2CID 198157398

- ^ Santorelli Jr, Sergio; Magnusson, William E.; Deus, Claudia P. (2018), "Most species are not limited by an Amazonian river postulated to be a border between endemism areas", Scientific Reports, 8 (2294): 2294, Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.2294S, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20596-7, PMC 5797105, PMID 29396491

- ^ Luciano N. Naka and Maria W. Pil (2020), "Moving beyond the riverine barrier vicariant paradigm", Molecular Ecology, 29 (12): 2129–2132, Bibcode:2020MolEc..29.2129N, doi:10.1111/mec.15465, PMID 32392379

- ^ Brian Tilston Smith; John E. McCormack; Andrés M. Cuervo; Michael. J. Hickerson; Alexandre Aleixo; Carlos Daniel Cadena; Jorge Pérez-Emán; Curtis W. Burney; Xiaoou Xie; Michael G. Harvey; Brant C. Faircloth; Travis C. Glenn; Elizabeth P. Derryberry; Jesse Prejean; Samantha Fields; Robb T. Brumfield (2014), "The drivers of tropical speciation", Nature, 515 (7527): 406–409, Bibcode:2014Natur.515..406S, doi:10.1038/nature13687, PMID 25209666, S2CID 1415798

- ^ C. K. Ghalambor; R. B. Huey; P. R. Martin; J. T. Tewksbury; G. Wang (2014), "Are mountain passes higher in the tropics? Janzen's hypothesis revisited", Integrative and Comparative Biology, 46 (1): 5–7, doi:10.1093/icb/icj003, PMID 21672718

- ^ Carina Hoorn; Volker Mosbrugger; Andreas Mulch; Alexandre Antonelli (2013), "Biodiversity from mountain building" (PDF), Nature Geoscience, 6 (3): 154, Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..154H, doi:10.1038/ngeo1742

- ^ Jon Fjeldså; Rauri C.K. Bowie; Carsten Rahbek (2012), "The Role of Mountain Ranges in the Diversification of Birds", Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 43: 249–265, doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145113, S2CID 85868089

- ^ Yaowu Xing; Richard H. Ree (2017), "Uplift-driven diversification in the Hengduan Mountains, a temperate biodiversity hotspot", PNAS, 114 (17): 3444–3451, Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E3444X, doi:10.1073/pnas.1616063114, PMC 5410793, PMID 28373546

- ^ Li Wang; Harald Schneider; Xian-Chun Zhang; Qiao-Ping Xiang (2012), "The rise of the Himalaya enforced the diversification of SE Asian ferns by altering the monsoon regimes", BMC Plant Biology, 12 (210): 1–9, doi:10.1186/1471-2229-12-210, PMC 3508991, PMID 23140168

- ^ Shunping He; Wenxuan Cao; Yiyu Chen (2001), "The uplift of Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau and the vicariance speciation of glyptosternoid fishes (Siluriformes: Sisoridae)", Science in China Series C: Life Sciences, 44 (6): 644–651, doi:10.1007/bf02879359, PMID 18763106, S2CID 22432209

- ^ Wei-Wei Zhou; Yang Wen; Jinzhong Fu; Yong-Biao Xu; Jie-Qiong Jin; Li Ding; Mi-Sook Min; Jing Che; Ya-Ping Zhang (2012), "Speciation in the Rana chensinensis species complex and its relationship to the uplift of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau", Molecular Ecology, 21 (4): 960–973, Bibcode:2012MolEc..21..960Z, doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05411.x, PMID 22221323, S2CID 37992915

- ^ Joanne Bentley; G Anthony Verboom; Nicola G Bergh (2014), "Erosive processes after tectonic uplift stimulate vicariant and adaptive speciation: evolution in an Afrotemperate-endemic paper daisy genus", BMC Evolutionary Biology, 14 (27): 1–16, Bibcode:2014BMCEE..14...27B, doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-27, PMC 3927823, PMID 24524661

- ^ Jason T. Weir; Momoko Price (2011), "Andean uplift promotes lowland speciation through vicariance and dispersal in Dendrocincla woodcreepers", Molecular Ecology, 20 (21): 4550–4563, Bibcode:2011MolEc..20.4550W, doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05294.x, PMID 21981112, S2CID 33626056

- ^ Terry A. Gates; Albert Prieto-Márquez; Lindsay E. Zanno (2012), "Mountain Building Triggered Late Cretaceous North American Megaherbivore Dinosaur Radiation", PLOS ONE, 7 (8): e42135, Bibcode:2012PLoSO...742135G, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042135, PMC 3410882, PMID 22876302

- ^ a b c Carla Hurt; Arthur Anker; Nancy Knowlton (2008), "A Multilocus Test of Simultaneous Divergence Across the Isthmus of Panama Using Snapping Shrimp in the Genus Alpheus", Evolution, 63 (2): 514–530, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00566.x, PMID 19154357, S2CID 11820649

- ^ C. Montes; A. Cardona; C. Jaramillo; A. Pardo; J. C. Silva; V. Valencia; C. Ayala; L. C. Pérez-Angel; L. A. Rodriguez-Parra; V. Ramirez; H. Niño; et al. (2015), "Middle Miocene closure of the Central American Seaway", Science, 348 (6231): 226–229, Bibcode:2015Sci...348..226M, doi:10.1126/science.aaa2815, PMID 25859042

- ^ Christine D. Bacon; Daniele Silvestro; Carlos Jaramillo; Brian Tilston Smith; Prosanta Chakrabarty; Alexandre Antonelli (2015), "Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama", PNAS, 112 (9): 6110–6115, Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.6110B, doi:10.1073/pnas.1423853112, PMC 4434730, PMID 25918375

- ^ Seàn Brady (2017), "Army ant invasions reveal phylogeographic processes across the Isthmus of Panama", Molecular Ecology, 26 (3): 703–705, Bibcode:2017MolEc..26..703B, doi:10.1111/mec.13981, PMID 28177197

- ^ Max E. Winston; Daniel J. C. Kronauer; Corrie S. Moreau (2017), "Early and dynamic colonization of Central America drives speciation in Neotropical army ants", Molecular Ecology, 26 (3): 859–870, Bibcode:2017MolEc..26..859W, doi:10.1111/mec.13846, PMID 27778409

- ^ Nancy Knowlton (1993), "Divergence in Proteins, Mitochondrial DNA, and Reproductive Compatibility Across the Isthmus of Panama", Science, 260 (5114): 1629–1632, Bibcode:1993Sci...260.1629K, doi:10.1126/science.8503007, PMID 8503007, S2CID 31875676

- ^ a b c Nancy Knowlton; Lee A. Weigt (1998), "New dates and new rates for divergence across the Isthmus of Panama", Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B, 265 (1412): 2257–2263, doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0568, PMC 1689526

- ^ H. A. Lessios. (1998). The first stage of speciation as seen in organisms separated by the Isthmus of Panama. In Endless forms: species and speciation (ed. D. Howard & S. Berlocher). Oxford University Press

- ^ a b c d Jason T. Weir; Dolph Schluter (2004), "Ice Sheets Promote Speciation in Boreal Birds", Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 271 (1551): 1881–1887, doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2803, PMC 1691815, PMID 15347509

- ^ Juan P. Jaramillo-Correa; Jean Bousquet (2003), "New evidence from mitochondrial DNA of a progenitor-derivative species relationship between black and red spruce (Pinaceae)", American Journal of Botany, 90 (12): 1801–1806, doi:10.3732/ajb.90.12.1801, PMID 21653356

- ^ Gabriela Castellanos-Morales; Niza Gámez; Reyna A. Castillo-Gámez; Luis E. Eguiarte (2016), "Peripatric speciation of an endemic species driven by Pleistocene climate change: The case of the Mexican prairie dog (Cynomys mexicanus)", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 94 (Pt A): 171–181, Bibcode:2016MolPE..94..171C, doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.08.027, PMID 26343460

- ^ Amadon D. (1966). "The superspecies concept". Systematic Biology. 15 (3): 245–249. doi:10.2307/sysbio/15.3.245.

- ^ Ernst Mayr; Jared Diamond (2001), The Birds of Northern Melanesia, Oxford University Press, p. 143, ISBN 978-0-19-514170-2

- ^ a b c Ernst Mayr (1963), Animal Species and Evolution, Harvard University Press, pp. 488–515, ISBN 978-0674037502

- ^ Remington C.L. (1968) Suture-Zones of Hybrid Interaction Between Recently Joined Biotas. In: Dobzhansky T., Hecht M.K., Steere W.C. (eds) Evolutionary Biology. Springer, Boston, MA

- ^ Jürgen Haffer (1969), "Speciation in Amazonian Forest Birds", Science, 165 (3889): 131–137, Bibcode:1969Sci...165..131H, doi:10.1126/science.165.3889.131, PMID 17834730

- ^ Ernst Mayr; Jared Diamond (2001), The Birds of Northern Melanesia, Oxford University Press, p. 127, ISBN 978-0-19-514170-2

- ^ François Vuilleumier (1985), "Forest Birds of Patagonia: Ecological Geography, Speciation, Endemism, and Faunal History", Ornithological Monographs (36): 255–304, doi:10.2307/40168287, JSTOR 40168287

- ^ Mayr, E., & Short, L. L. (1970). Species taxa of North American birds: a contribution to comparative systematics.

- ^ Hall, B. P., & Moreau, R. E. (1970). An atlas of speciation in African passerine birds. Trustees of the British museum (Natural history).

- ^ J. R. Powell; M. Andjelkovic (1983), "Population genetics of Drosophila amylase. IV. Selection in laboratory populations maintained on different carbohydrates", Genetics, 103 (4): 675–689, doi:10.1093/genetics/103.4.675, PMC 1202048, PMID 6189764

- ^ a b Diane M. B. Dodd (1989), "Reproductive Isolation as a Consequence of Adaptive Divergence in Drosophila pseudoobscura", Evolution, 43 (6): 1308–1311, doi:10.2307/2409365, JSTOR 2409365, PMID 28564510

- ^ a b c d Ann-Britt Florin; Anders Ödeen (2002), "Laboratory environments are not conducive for allopatric speciation", Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15: 10–19, doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00356.x, S2CID 85410953

- ^ a b Mark Kirkpatrick; Virginie Ravigné (2002), "Speciation by Natural and Sexual Selection: Models and Experiments", The American Naturalist, 159 (3): S22, doi:10.2307/3078919, JSTOR 3078919

- ^ Bishop, Y. M.; Fienberg, S. E.; Holland, P. W. (1975), Discrete Multivariate Analysis: Theory and Practice, MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

- ^ H. D. Stalker (1942), "Sexual isolation studies in the species complex Drosophila virilis", Genetics, 27 (2): 238–257, doi:10.1093/genetics/27.2.238, PMC 1209156, PMID 17247038

- ^ Jerry A. Coyne; H. Allen Orr (1997), ""Patterns of Speciation in Drosophila" Revisited", Evolution, 51 (1): 295–303, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02412.x, PMID 28568795, S2CID 40390753

- ^ B. S. Grant; L. E. Mettler (1969), "Disruptive and stabilizing selection on the" escape" behavior of Drosophila melanogaster", Genetics, 62 (3): 625–637, doi:10.1093/genetics/62.3.625, PMC 1212303, PMID 17248452

- ^ B. Burnet; K. Connolly (1974), "Activity and sexual behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster", The Genetics of Behaviour: 201–258

- ^ G. Kilias; S. N. Alahiotis; M. Pelecanos (1980), "A Multifactorial Genetic Investigation of Speciation Theory Using Drosophila melanogaster", Evolution, 34 (4): 730–737, doi:10.2307/2408027, JSTOR 2408027, PMID 28563991

- ^ C. R. B. Boake; K. Mcdonald; S. Maitra; R. Ganguly (2003), "Forty years of solitude: life-history divergence and behavioural isolation between laboratory lines of Drosophila melanogaster", Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 16 (1): 83–90, doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00505.x, PMID 14635883, S2CID 24040182

- ^ J. S. F. Barker; L. J. E. Karlsson (1974), "Effects of population size and selection intensity on responses to disruptive selection in Drosophila melanogaster", Genetics, 78 (2): 715–735, doi:10.2307/2407287, JSTOR 2407287, PMC 1213230, PMID 4217303

- ^ Stella A. Crossley (1974), "Changes in Mating Behavior Produced by Selection for Ethological Isolation Between Ebony and Vestigial Mutants of Drosophila melanogaster", Evolution, 28 (4): 631–647, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1974.tb00795.x, PMID 28564833, S2CID 35867118

- ^ F. R. van Dijken; W. Scharloo (1979), "Divergent selection on locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Selection response", Behavior Genetics, 9 (6): 543–553, doi:10.1007/BF01067350, PMID 122270, S2CID 39352792

- ^ F. R. van Dijken; W. Scharloo (1979), "Divergent selection on locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster. II. Test for reproductive isolation between selected lines", Behavior Genetics, 9 (6): 555–561, doi:10.1007/BF01067351, PMID 122271, S2CID 40169222

- ^ B. Wallace (1953), "Genetic divergence of isolated populations of Drosophila melanogaster", Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Genetics, 9: 761–764

- ^ G. R. Knight; et al. (1956), "Selection for sexual isolation within a species", Evolution, 10: 14–22, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1956.tb02825.x, S2CID 87729275

- ^ Forbes W. Robertson (1966), "A test of sexual isolation in Drosophila", Genetical Research, 8 (2): 181–187, doi:10.1017/s001667230001003x, PMID 5922518

- ^ Forbes W. Robertson (1966), "The ecological genetics of growth in Drosophila 8. Adaptation to a New Diet", Genetical Research, 8 (2): 165–179, doi:10.1017/s0016672300010028, PMID 5922517

- ^ Ellen E. Hostert (1997), "Reinforcement: a new perspective on an old controversy", Evolution, 51 (3): 697–702, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb03653.x, PMID 28568598, S2CID 21054233

- ^ Koref Santibañez, S.; Waddington, C. H. (1958), "The origin of sexual isolation between different lines within a species", Evolution, 12 (4): 485–493, doi:10.2307/2405959, JSTOR 2405959

- ^ Barker, J. S. F.; Cummins, L. J. (1969), "The effect of selection for sternopleural bristle number in mating behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster", Genetics, 61 (3): 713–719, doi:10.1093/genetics/61.3.713, PMC 1212235, PMID 17248436

- ^ Markow, T. A. (1975), "A genetic analysis of phototactic behavior in Drosophila melanogaster", Genetics, 79 (3): 527–534, doi:10.1093/genetics/79.3.527, PMC 1213291, PMID 805084

- ^ Markow, T. A. (1981), "Mating preferences are not predictive of the direction of evolution in experimental populations of Drosophila", Science, 213 (4514): 1405–1407, Bibcode:1981Sci...213.1405M, doi:10.1126/science.213.4514.1405, PMID 17732575, S2CID 15497733

- ^ Rundle, H. D.; Mooers, A. Ø.; Whitlock, M. C. (1998), "Single founder-flush events and the evolution of reproductive isolation", Evolution, 52 (6): 1850–1855, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb02263.x, JSTOR 2411356, PMID 28565304, S2CID 24502821

- ^ Mooers, A. Ø.; Rundle, H. D.; Whitlock, M. C. (1999), "The effects of selection and bottlenecks on male mating success in peripheral isolates", American Naturalist, 153 (4): 437–444, Bibcode:1999ANat..153..437M, doi:10.1086/303186, PMID 29586617, S2CID 4411105

- ^ Lee Ehrman (1971), "Natural selection and the origin of reproductive isolation", American Naturalist, 105 (945): 479–483, Bibcode:1971ANat..105..479E, doi:10.1086/282739, S2CID 85401244

- ^ Lee Ehrman (1973), "More on natural selection and the origin of reproductive isolation", American Naturalist, 107 (954): 318–319, Bibcode:1973ANat..107..318E, doi:10.1086/282835, S2CID 83780632

- ^ Lee Ehrman (1979), "Still more on natural selection and the origin of reproductive isolation", American Naturalist, 113 (1): 148–150, Bibcode:1979ANat..113..148E, doi:10.1086/283371, S2CID 85237458

- ^ Lee Ehrman (1983), "Fourth report on natural selection for the origin of reproductive isolation", American Naturalist, 121 (3): 290–293, Bibcode:1983ANat..121..290E, doi:10.1086/284059, S2CID 83654887

- ^ John Ringo; David Wood; Robert Rockwell; Harold Dowse (1985), "An Experiment Testing Two Hypotheses of Speciation", The American Naturalist, 126 (5): 642–661, Bibcode:1985ANat..126..642R, doi:10.1086/284445, S2CID 84819968

- ^ T. Dobzhansky; O. Pavlovsky; J. R. Powell (1976), "Partially Successful Attempt to Enhance Reproductive Isolation Between Semispecies of Drosophila paulistorum", Evolution, 30 (2): 201–212, doi:10.2307/2407696, JSTOR 2407696, PMID 28563045

- ^ T. Dobzhansky; O. Pavlovsky (1966), "Spontaneous origin of an incipient species in the Drosophila paulistorum complex", PNAS, 55 (4): 723–733, Bibcode:1966PNAS...55..727D, doi:10.1073/pnas.55.4.727, PMC 224220, PMID 5219677

- ^ Alice Kalisz de Oliveira; Antonio Rodrigues Cordeiro (1980), "Adaptation of Drosophila willistoni experimental populations to extreme pH medium", Heredity, 44: 123–130, doi:10.1038/hdy.1980.11

- ^ L. Ehrman (1964), "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura", Genetical Research, 5: 150–157, doi:10.1017/s0016672300001099

- ^ L. Ehrman (1969), "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura. 5. A further study of rudiments of sexual isolation", American Midland Naturalist, 82 (1): 272–276, doi:10.2307/2423835, JSTOR 2423835

- ^ Eduardo del Solar (1966), "Sexual isolation caused by selection for positive and negative phototaxis and geotaxis in Drosophila pseudoobscura", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 56 (2): 484–487, Bibcode:1966PNAS...56..484D, doi:10.1073/pnas.56.2.484, PMC 224398, PMID 5229969

- ^ Jeffrey R. Powell (1978), "The Founder-Flush Speciation Theory: An Experimental Approach", Evolution, 32 (3): 465–474, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1978.tb04589.x, JSTOR 2407714, PMID 28567948, S2CID 30943286

- ^ Diane M. B. Dodd; Jeffrey R. Powell (1985), "Founder-Flush Speciation: An Update of Experimental Results with Drosophila", Evolution, 39 (6): 1388–1392, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb05704.x, JSTOR 2408795, PMID 28564258, S2CID 34137489

- ^ Galiana, A.; Moya, A.; Ayala, F. J. (1993), "Founder-flush speciation in Drosophila pseudoobscura: a large scale experiment", Evolution, 47 (2): 432–444, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02104.x, JSTOR 2410062, PMID 28568735, S2CID 42232235

- ^ Rundle, H. D. (2003), "Divergent environments and population bottlenecks fail to generate premating isolation in Drosophila pseudoobscura", Evolution, 57 (11): 2557–2565, doi:10.1554/02-717, PMID 14686531, S2CID 6162106

- ^ Karl F. Koopman (1950), "Natural Selection for Reproductive Isolation Between Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis", Evolution, 4 (2): 135–148, doi:10.2307/2405390, JSTOR 2405390

- ^ Seymour Kessler (1966), "Selection For and Against Ethological Isolation Between Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis", Evolution, 20 (4): 634–645, doi:10.2307/2406597, JSTOR 2406597, PMID 28562900

- ^ H. Roberta Koepfer (1987), "Selection for Sexual Isolation Between Geographic Forms of Drosophila mojavensis. I Interactions Between the Selected Forms", Evolution, 41 (1): 37–48, doi:10.2307/2408971, JSTOR 2408971, PMID 28563762

- ^ Etges, W. J. (1998), "Premating isolation is determined by larval rearing substrates in cactophilis Drosophila mojavensis. IV. Correlated responses in behavioral isolation to artificial selection on a life-history trait", American Naturalist, 152 (1): 129–144, doi:10.1086/286154, PMID 18811406, S2CID 17689372

- ^ Lorna H. Arita; Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro (1979), "Ethological Isolation Between Two Stocks of Drosophila Adiastola Hardy", Proc. Hawaii. Entomol. Soc., 13: 31–34

- ^ J. N. Ahearn (1980), "Evolution of behavioral reproductive isolation in a laboratory stock of Drosophila silvestris", Experientia, 36 (1): 63–64, doi:10.1007/BF02003975, S2CID 43809774

- ^ A. Benedict Soans; David Pimentel; Joyce S. Soans (1974), "Evolution of Reproductive Isolation in Allopatric and Sympatric Populations", The American Naturalist, 108 (959): 117–124, Bibcode:1974ANat..108..117S, doi:10.1086/282889, S2CID 84913547

- ^ L. E. Hurd; Robert M. Eisenberg (1975), "Divergent Selection for Geotactic Response and Evolution of Reproductive Isolation in Sympatric and Allopatric Populations of Houseflies", The American Naturalist, 109 (967): 353–358, Bibcode:1975ANat..109..353H, doi:10.1086/283002, S2CID 85084378

- ^ Meffert, L. M.; Bryant, E. H. (1991), "Mating propensity and courtship behavior in serially bottlenecked lines of the housefly", Evolution, 45 (2): 293–306, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb04404.x, JSTOR 2409664, PMID 28567864, S2CID 13379387

- ^ Takahisa Miyatake; Toru Shimizu (1999), "Genetic correlations between life-history and behavioral traits can cause reproductive isolation", Evolution, 53 (1): 201–208, doi:10.2307/2640932, JSTOR 2640932, PMID 28565193

- ^ Paterniani, E. (1969), "Selection for Reproductive Isolation between Two Populations of Maize, Zea mays L", Evolution, 23 (4): 534–547, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1969.tb03539.x, PMID 28562870, S2CID 38650254

- ^ Anders Ödeen; Ann-Britt Florin (2002), "Sexual selection and peripatric speciation: the Kaneshiro model revisited", Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15 (2): 301–306, doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00378.x, S2CID 82095639

- ^ a b David Starr Jordan (1905), "The Origin of Species Through Isolation", Science, 22 (566): 545–562, Bibcode:1905Sci....22..545S, doi:10.1126/science.22.566.545, PMID 17832412

- ^ a b c d James Mallet (2010), "Why was Darwin's view of species rejected by twentieth century biologists?", Biology & Philosophy, 25 (4): 497–527, doi:10.1007/s10539-010-9213-7, S2CID 38621736

- ^ Mayr, Ernst 1942. Systematics and origin of species. Columbia University Press, New York. p148

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species. Murray. p. 347.

- ^ Sulloway FJ (1979). "Geographic isolation in Darwin's thinking: the vicissitudes of a crucial idea". Studies in the History of Biology. 3: 23–65. PMID 11610987.

- ^ David Starr Jordan (1908), "The Law of Geminate Species", American Naturalist, 42 (494): 73–80, Bibcode:1908ANat...42...73J, doi:10.1086/278905

- ^ Joel Asaph Allen (1907), "Mutations and the Geographic Distribution of Nearly Related Species in Plants and Animals", American Naturalist, 41 (490): 653–655, Bibcode:1907ANat...41..653A, doi:10.1086/278852

- ^ Ernst Mayr (1982), The Growth of Biological Thought, Harvard University Press, pp. 561–566, ISBN 978-0674364462

- ^ a b James Mallet (2001), "The speciation revolution", Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 14 (6): 887–888, doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00342.x, S2CID 36627140

- ^ a b Catherine H. Graham; Santiago R. Ron Juan C. Santos; Christopher J. Schneider; Craig Moritz (2004), "Integrating Phylogenetics and Environmental Niche Models to Explore Speciation Mechanisms in Dendrobatid Frogs", Evolution, 58 (8): 1781–1793, doi:10.1554/03-274, PMID 15446430, S2CID 198157565

- ^ C. Yesson; N.H. Toomey; A. Culham (2009), "Cyclamen: time, sea and speciation biogeography using a temporally calibrated phylogeny", Journal of Biogeography, 36 (7): 1234–1252, Bibcode:2009JBiog..36.1234Y, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01971.x, S2CID 85573501

- ^ Robert M. Zink (2012), "The Geography of Speciation: Case Studies from Birds", Evolution: Education and Outreach, 5 (4): 541–546, doi:10.1007/s12052-012-0411-4

- ^ R. T. Chesser; R. M. Zink (1994), "Modes of speciation in birds: a test of Lynch's method", Evolution, 48 (2): 490–497, doi:10.2307/2410107, JSTOR 2410107, PMID 28568302

- ^ Matthew T. Webster (2009), "Patterns of autosomal divergence between the human and chimpanzee genomes support an allopatric model of speciation", Gene, 443 (1–2): 70–75, doi:10.1016/j.gene.2009.05.006, PMID 19463924

- ^ Taylor Edwards; Marc Tollis; PingHsun Hsieh; Ryan N. Gutenkunst; Zhen Liu; Kenro Kusumi; Melanie Culver; Robert W. Murphy (2016), "Assessing models of speciation under different biogeographic scenarios; an empirical study using multi-locus and RNA-seq analyses", Ecology and Evolution, 6 (2): 379–396, Bibcode:2016EcoEv...6..379E, doi:10.1002/ece3.1865, PMC 4729248, PMID 26843925

Further reading

[edit]Mathematical models of reproductive isolation

- H. Allen Orr; Michael Turelli (2001), "The evolution of postzygotic isolation: Accumulating Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities", Evolution, 55 (6): 1085–1094, arXiv:0904.3308, doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[1085:teopia]2.0.co;2, PMID 11475044, S2CID 198153495

- H. Allen Orr; Lynne H. Orr (1996), "Waiting for Speciation: The Effect of Population Subdivision on the Time to Speciation", Evolution, 50 (5): 1742–1749, doi:10.2307/2410732, JSTOR 2410732, PMID 28565607

- H. Allen Orr (1995), "The Population Genetics of Speciation: The Evolution of Hybrid Incompatibilities", Genetics, 139 (4): 1805–1813, doi:10.1093/genetics/139.4.1805, PMC 1206504, PMID 7789779

- Masatoshi Nei; Takeo Maruyama; Chung-i Wu (1983), "Models of Evolution of Reproductive Isolation", Genetics, 103 (3): 557–579, doi:10.1093/genetics/103.3.557, PMC 1202040, PMID 6840540

- Masatoshi Nei (1976), "Mathematical Models of Speciation and Genetic Distance", Population Genetics and Ecology: 723–766