Sherman's March to the Sea

| Sherman's March to the Sea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Sherman's March to the Sea, Alexander Hay Ritchie | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Army of the Tennessee[1] Army of Georgia[1] | Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 62,204[2] | 12,466[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| More than 1,300 casualties | Around 2,300 casualties | ||||||

| Economic loss: $100 million[4] | |||||||

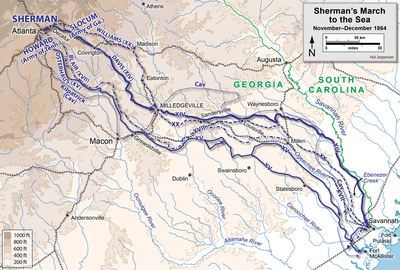

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, major general of the Union Army. The campaign began on November 15 with Sherman's troops leaving Atlanta, recently taken by Union forces, and ended with the capture of the port of Savannah on December 21. His forces followed a "scorched earth" policy, destroying military targets as well as industry, infrastructure, and civilian property, disrupting the Confederacy's economy and transportation networks.

The operation debilitated the Confederacy and helped lead to its eventual surrender.[5] Sherman's decision to operate deep within enemy territory without supply lines was unusual for its time, and the campaign is regarded by some historians as an early example of total war or "hard war" in modern warfare.

Following the March to the Sea, Sherman's army headed north for the Carolinas campaign. The portion of this march through South Carolina was even more destructive than the Savannah campaign, since Sherman and his men harbored much ill-will for that state's part in bringing on the Civil War; the following portion, through North Carolina, was less so.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The March to the Sea owes its common name to a poem written by S. H. M. Byers in late 1864. Byers was a Union prisoner of war held at Camp Sorghum, near Columbia, South Carolina. During his imprisonment, Byers wrote a poem about the Savannah campaign, which he titled "Sherman's March to the Sea" and which was set to music by fellow prisoner W. O. Rockwell.[7]

When Byers was freed by the Union Capture of Columbia, he approached General Sherman and handed him a scrap of paper. On it was Byers' poem. Reading the paper later in the day, Sherman was so moved by Byers' poem that he promoted Byers to his staff where the two became lifelong friends. The poem would go on to lend its name to Sherman's campaign, and a version set to music became an instant hit with Sherman's Army and later the public.[8][7][9]

Background and objectives

[edit]Military situation

[edit]Sherman's "March to the Sea" followed his successful Atlanta Campaign of May to September 1864. He and the Union Army's commander, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, believed that the Civil War would come to an end only if the Confederacy's strategic capacity for warfare could be decisively broken.[10] Sherman therefore planned an operation that has been compared to the modern principles of scorched earth warfare. Although his formal orders specified control over destruction of infrastructure in areas in which his army was unmolested by guerrilla activity, he recognized that supplying an army through liberal foraging would have a destructive effect on the morale of the civilian population it encountered in its wide sweep through the state.[11]

The second objective of the campaign was more traditional. Grant's armies in Virginia continued in a stalemate against Robert E. Lee's army, besieged in Petersburg, Virginia. By encroaching into the rear of Lee's positions, Sherman could increase pressure on Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and keep Confederate reinforcements from reaching him.

The campaign was designed by Grant and Sherman to be similar to Grant's innovative and successful Vicksburg campaign and Sherman's Meridian campaign, in that Sherman's armies would reduce their need for traditional supply lines by "living off the land" after consuming their 20 days of rations. Foragers, known as "bummers", would provide food seized from local farms for the army while they destroyed the railroads and the manufacturing and agricultural infrastructure of Georgia. In planning for the march, Sherman used livestock and crop production data from the 1860 census to lead his troops through areas where he believed they would be able to forage most effectively.[12] The twisted and broken railroad rails that the troops heated over fires, wrapped around tree trunks and left behind became known as Sherman's neckties.

Orders

[edit]As the army would be out of touch with the North throughout the campaign, Sherman gave explicit orders, Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 120, regarding the conduct of the campaign. The following is an excerpt from those orders:

... IV. The army will forage liberally on the country during the march. To this end, each brigade commander will organize a good and sufficient foraging party, under the command of one or more discreet officers, who will gather, near the route traveled, corn or forage of any kind, meat of any kind, vegetables, corn-meal, or whatever is needed by the command, aiming at all times to keep in the wagons at least ten days' provisions for the command and three days' forage. Soldiers must not enter the dwellings of the inhabitants, or commit any trespass, but during a halt or a camp they may be permitted to gather turnips, apples, and other vegetables, and to drive in stock in sight of their camp. To regular foraging parties must be intrusted the gathering of provisions and forage at any distance from the road traveled.

V. To army corps commanders alone is intrusted the power to destroy mills, houses, cotton-gins, &c., and for them this general principle is laid down: In districts and neighborhoods where the army is unmolested no destruction of such property should be permitted; but should guerrillas or bushwhackers molest our march, or should the inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads, or otherwise manifest local hostility, then army commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or less relentless according to the measure of such hostility.

VI. As for horses, mules, wagons, &c., belonging to the inhabitants, the cavalry and artillery may appropriate freely and without limit, discriminating, however, between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly. Foraging parties may also take mules or horses to replace the jaded animals of their trains, or to serve as pack-mules for the regiments or brigades. In all foraging, of whatever kind, the parties engaged will refrain from abusive or threatening language, and may, where the officer in command thinks proper, give written certificates of the facts, but no receipts, and they will endeavor to leave with each family a reasonable portion for their maintenance.

VII. Negroes who are able-bodied and can be of service to the several columns may be taken along, but each army commander will bear in mind that the question of supplies is a very important one and that his first duty is to see to them who bear arms...

— William T. Sherman, Military Division of the Mississippi Special Field Order 120, November 9, 1864.

Opposing forces

[edit]Union

[edit]

Sherman, commanding the Military Division of the Mississippi, did not employ his entire army group in the campaign. Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood was threatening Chattanooga, and Sherman detached two armies under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas to deal with Hood in the Franklin–Nashville campaign.[1] Thomas would go on to defeat Hood, leaving Sherman's main army effectively unopposed.[13]

When Sherman had prepared his forces for the Atlanta Campaign, which immediately preceded the March to the Sea, he took rigorous steps to ensure that only the most physically fit men were accepted, that every man in the army could march for long distances and would fight without reservations. Sherman wanted only the "best fighting material." Doctors performed in-depth examinations to weed out the weak and those suffering from disease, and because of this 1% of the men were left behind. Eighty percent of the remaining soldiers were long-time veterans of campaigns in both the Western theatre, primarily, and the Eastern, a minority.[14]

Sherman had ruthlessly cut to the bone the supplies carried, intending as he did for the army to live off the land as much as possible. Each division and brigade had a supply train, but the size of the train was strictly limited. Each regiment had one wagon and one ambulance, and each company had one pack mule for the baggage of its officers; the number of tents carried was curtailed. The staffs of the various headquarters were ruthlessly restricted, and much clerical work was done by permanent offices in the rear.[15]

This was the process by which the 62,000 men (55,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 2,000 artillerymen manning 64 guns) Sherman commanded were assembled, and would leave Atlanta for Savannah. They were divided into two columns for the march:[1]

- The right wing was the Army of the Tennessee, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, consisting of two corps:

- XV Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. Charles R. Woods, William B. Hazen, John E. Smith, and John M. Corse.

- XVII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Frank Blair Jr., with the divisions of Maj. Gen. Joseph A. Mower and Brig. Gens. Mortimer D. Leggett and Giles A. Smith.

- The left wing was the Army of Georgia, commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, also with two corps:

- XIV Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. William P. Carlin, James D. Morgan, and Absalom Baird.

- XX Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. Nathaniel J. Jackson, John W. Geary, and William T. Ward.

- A cavalry division under Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick operated in support of the two wings, and reported directly to Sherman.

In 1929, British military historian B. H. Liddell Hart described the men of Sherman's army as "probably the finest army of military 'workmen' the modern world has seen. An army of individuals trained in the school of experience to look after their own food and health, to march far and fast with the least fatigue, to fight with the least exposure, above all, to act swiftly and to work thoroughly."[16] After his surrender to Sherman, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston said of Sherman's men that "there has been no such army since the days of Julius Caesar."[17]

Confederate

[edit]The Confederate opposition from Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee's Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida was meager. Hood had taken the bulk of forces in Georgia on his campaign to Tennessee in hopes of diverting Sherman to pursue him. Considering Sherman's military priorities, however, this tactical maneuver by his enemy to get out of his force's path was welcomed to the point of remarking, "If he will go to the Ohio River, I'll give him rations."[18] There were about 13,000 men remaining at Lovejoy's Station, south of Atlanta. Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith's Georgia militia had about 3,050 soldiers, most of whom were boys and elderly men. The Cavalry Corps of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, reinforced by a brigade under Brig. Gen. William H. Jackson, had approximately 10,000 troopers. During the campaign, the Confederate War Department brought in additional men from Florida and the Carolinas, but they never were able to increase their effective force beyond 13,000.[19]

March

[edit]Both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant had serious reservations about Sherman's plans.[20] Still, Grant trusted Sherman's assessment and on November 2, 1864, he sent Sherman a telegram stating simply, "Go as you propose."[21] The 300-mile (480 km) march began on November 15. Sherman recounted in his memoirs the scene when he left at 7 am the following day:

... We rode out of Atlanta by the Decatur road, filled by the marching troops and wagons of the Fourteenth Corps; and reaching the hill, just outside of the old rebel works, we naturally paused to look back upon the scenes of our past battles. We stood upon the very ground whereon was fought the bloody battle of July 22d, and could see the copse of wood where McPherson fell. Behind us lay Atlanta, smouldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in air, and hanging like a pall over the ruined city. Away off in the distance, on the McDonough road, was the rear of Howard's column, the gun-barrels glistening in the sun, the white-topped wagons stretching away to the south; and right before us the Fourteenth Corps, marching steadily and rapidly, with a cheery look and swinging pace, that made light of the thousand miles that lay between us and Richmond. Some band, by accident, struck up the anthem of "John Brown's Body"; the men caught up the strain, and never before or since have I heard the chorus of "Glory, glory, hallelujah!" done with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.

— William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, Chapter 21

Sherman's personal escort on the march was the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment, a unit made up entirely of Southerners who remained loyal to the Union.

The two wings of the army attempted to confuse and deceive the enemy about their destinations; the Confederates could not tell from the initial movements whether Sherman would march on Macon, Augusta, or Savannah. Howard's wing, led by Kilpatrick's cavalry, marched south along the railroad to Lovejoy's Station, which caused the defenders there to conduct a fighting retreat to Macon. The cavalry captured two Confederate guns at Lovejoy's Station, and then two more and 50 prisoners at Bear Creek Station. Howard's infantry marched through Jonesboro to Gordon, southwest of the state capital, Milledgeville. Slocum's wing, accompanied by Sherman, moved to the east, in the direction of Augusta. They destroyed the bridge across the Oconee River and then turned south.[22]

The first real resistance was felt by Howard's right wing at the Battle of Griswoldville on November 22. Confederate Maj. Gen. Wheeler's cavalry struck Brig. Gen. Kilpatrick's, killing one, wounding two and capturing 18. The infantry brigade of Brig. Gen. Charles C. Walcutt arrived to stabilize the defense, and the division of Georgia militia launched several hours of badly coordinated attacks, eventually retreating with about 1,100 casualties (of which about 600 were prisoners), versus the Union's 100.

At the same time, Slocum's left wing approached the state capital at Milledgeville, prompting the hasty departure of Governor Joseph Brown and the state legislature. On November 23, Slocum's troops captured the city and held a mock legislative session in the capitol building, jokingly voting Georgia back into the Union.[23]

Several small actions followed. Wheeler and some infantry struck in a rearguard action at Ball's Ferry on November 24 and November 25. While Howard's wing was delayed near Ball's Bluff, the 1st Alabama Cavalry (a Federal regiment) engaged Confederate pickets. Overnight, Union engineers constructed a bridge 2 miles (3.2 km) away from the bluff across the Oconee River, and 200 soldiers crossed to flank the Confederate position. On November 25–26 at Sandersville, Wheeler struck at Slocum's advance guard. Kilpatrick was ordered to make a feint toward Augusta before destroying the railroad bridge at Brier Creek and moving to liberate the Camp Lawton prisoner of war camp at Millen. Kilpatrick slipped by the defensive line that Wheeler had placed near Brier Creek, but on the night of November 26 Wheeler attacked and drove the 8th Indiana and 2nd Kentucky Cavalry away from their camps at Sylvan Grove. Kilpatrick abandoned his plans to destroy the railroad bridge and he also learned that the prisoners had been moved from Camp Lawton, so he rejoined the army at Louisville. At the Battle of Buck Head Creek on November 28, Kilpatrick was surprised and nearly captured, but the 5th Ohio Cavalry halted Wheeler's advance, and Wheeler was later stopped decisively by Union barricades at Reynolds's Plantation. On December 4, Kilpatrick's cavalry routed Wheeler's at the Battle of Waynesboro.

More Union troops entered the campaign from an unlikely direction. Maj. Gen. John G. Foster dispatched 5,500 men and 10 guns under Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch from Hilton Head, hoping to assist Sherman's arrival near Savannah by securing the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. At the Battle of Honey Hill on November 30, Hatch fought a vigorous battle against G.W. Smith's 1,500 Georgia militiamen, 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Grahamville Station, South Carolina. Smith's militia fought off the Union attacks, and Hatch withdrew after suffering about 650 casualties, versus Smith's 50.

Sherman's armies reached the outskirts of Savannah on December 10 but found that Hardee had entrenched 10,000 men in favorable fighting positions, and his soldiers had flooded the surrounding rice fields, leaving only narrow causeways available to approach the city. Sherman was blocked from linking up with the U.S. Navy as he had planned, so he dispatched cavalry to Fort McAllister, guarding the Ogeechee River, in hopes of unblocking his route and obtaining supplies awaiting him on the Navy ships. On December 13, William B. Hazen's division of Howard's wing stormed the fort in the Battle of Fort McAllister and captured it within 15 minutes. Some of the 134 Union casualties were caused by torpedoes, a name for crude land mines that were used only rarely in the war.

Now that Sherman had contact with the Navy fleet under Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, he was able to obtain the supplies and siege artillery he required to invest Savannah. On December 17, he sent a message to Hardee in the city:

I have already received guns that can cast heavy and destructive shot as far as the heart of your city; also, I have for some days held and controlled every avenue by which the people and garrison of Savannah can be supplied, and I am therefore justified in demanding the surrender of the city of Savannah, and its dependent forts, and shall wait a reasonable time for your answer, before opening with heavy ordnance. Should you entertain the proposition, I am prepared to grant liberal terms to the inhabitants and garrison; but should I be forced to resort to assault, or the slower and surer process of starvation, I shall then feel justified in resorting to the harshest measures, and shall make little effort to restrain my army—burning to avenge the national wrong which they attach to Savannah and other large cities which have been so prominent in dragging our country into civil war.

— William T. Sherman, Message to William J. Hardee, December 17, 1864, recorded in his memoirs

Hardee decided not to surrender but to escape. Historian Barrett assesses that Sherman could have stopped Hardee, but failed to because he was hesitant to overcommit his forces.[13] On December 20, Hardee led his men across the Savannah River on a makeshift pontoon bridge. The next morning, Savannah Mayor Richard Dennis Arnold, with a delegation of aldermen and ladies of the city, rode out (until they were unhorsed by fleeing Confederate cavalrymen) to offer a proposition: The city would surrender and offer no resistance, in exchange for General Geary's promise to protect the city's citizens and their property. Geary telegraphed Sherman, who advised him to accept the offer. Arnold presented him with the key to the city, and Sherman's men, led by Geary's division of the XX Corps, occupied the city the same day.[24][better source needed]

Aftermath

[edit]

Sherman telegraphed to President Lincoln, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton."[25] On December 26, the president replied in a letter:[26]

Many, many thanks for your Christmas gift, the capture of Savannah. When you were about leaving Atlanta for the Atlantic coast, I was anxious, if not fearful; but feeling that you were the better judge, and remembering that 'nothing risked, nothing gained,' I did not interfere. Now, the undertaking being a success, the honor is yours; for I believe none of us went further than to acquiesce. And taking the work of General Thomas into the count, as it should be taken, it is indeed a great success. Not only does it afford the obvious and immediate military advantages, but, in showing to the world that your army could be divided, putting the stronger part to an important new service, and yet leaving enough to vanquish the old opposing force of the whole – Hood's army – it brings those who sat in darkness to see a great light. But what next? I suppose it will be safer if I leave General Grant and yourself to decide. Please make my grateful acknowledgments to your whole army, officers and men.

The March attracted a huge number of refugees, to whom Sherman assigned land with his Special Field Orders No. 15. These orders have been depicted in popular culture as the origin of the "40 acres and a mule" promise.[27]

The Army's stay in Savannah was generally without incident. The Army was on its best behavior, in part because anyone caught doing "unsoldier-like deeds" was to be summarily executed.[28] As the Army recuperated, Sherman quickly tackled a variety of local problems. He organized relief for the flood of refugees that had inundated the city. Sherman further arranged for 50,000 bushels of captured rice to be sold in the North to raise money to feed Savannah. While the local high society turned its nose up at the Union Army, refusing to be seen at social events with Union officers present, Sherman was ironically focused on protecting them. Sherman received numerous letters from the very Confederate officers he was fighting against, requesting that Sherman ensure the protection of their families. Sherman dutifully complied with the letters of protection he received, from both North and South, regardless of social standing.[29]

From Savannah, after a month-long delay for rest, Sherman marched north in the spring in the Carolinas Campaign, intending to complete his turning movement and combine his armies with Grant's against Robert E. Lee. Sherman's next major action was the capture of Columbia, the strategically important capital of South Carolina.[30] After a successful two-month campaign, Sherman accepted the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston and his forces in North Carolina on April 26, 1865.[31]

We are not only fighting armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect. Thousands who had been deceived by their lying papers into the belief that we were being whipped all the time, realized the truth, and have no appetite for a repetition of the same experience.

Sherman's scorched earth policies have always been highly controversial, and Sherman's memory has long been reviled by many Southerners. Slaves' opinions varied concerning the actions of Sherman and his army.[33] Some who welcomed him as a liberator chose to follow his armies. Jacqueline Campbell has written, on the other hand, that some slaves looked upon the Union army's ransacking and invasive actions with disdain. They often felt betrayed, as they "suffered along with their owners, complicating their decision of whether to flee with or from Union troops", although that is now seen as a post synopsis of Confederate nationalism.[34] A Confederate officer estimated that 10,000 liberated slaves followed Sherman's army, and hundreds died of "hunger, disease, or exposure" along the way.[4]

The March to the Sea was devastating to Georgia and the Confederacy. Sherman himself estimated that the campaign had inflicted $100 million (equivalent to $982 million in 2023) in destruction, about one fifth of which "inured to our advantage" while the "remainder is simple waste and destruction".[4] The Army wrecked 300 miles (480 km) of railroad and numerous bridges and miles of telegraph lines. It seized 5,000 horses, 4,000 mules, and 13,000 head of cattle. It confiscated 9.5 million pounds of corn and 10.5 million pounds of fodder, and destroyed uncounted cotton gins and mills.[35] Military historians Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones cited the significant damage wrought to railroads and Southern logistics in the campaign and stated that "Sherman's raid succeeded in 'knocking the Confederate war effort to pieces'."[36] David J. Eicher wrote that "Sherman had accomplished an amazing task. He had defied military principles by operating deep within enemy territory and without lines of supply or communication. He destroyed much of the South's potential and psychology to wage war."[37]

According to a 2022 American Economic Journal study which sought to measure the medium- and long-term economic impact of Sherman's March, "the capital destruction induced by the March led to a large contraction in agricultural investment, farming asset prices, and manufacturing activity. Elements of the decline in agriculture persisted through 1920".[38]

Legacy

[edit]

Union soldiers sang many songs during the March, but it is one written afterward that has come to symbolize the campaign: "Marching Through Georgia", written by Henry Clay Work in 1865. Sung from the point of view of a Union soldier, the lyrics detail the freeing of slaves and punishing the Confederacy for starting the war. Sherman came to dislike the song, in part because he was never one to rejoice over a fallen foe, and in part because it was played at almost every public appearance that he attended.[39] It was widely popular among US soldiers of 20th-century wars.

Hundreds of African Americans drowned trying to cross in Ebenezer Creek north of Savannah while attempting to follow Sherman's Army in its March to the Sea. In 2011, a historical marker was erected there by the Georgia Historical Society to commemorate the African Americans who had risked so much for freedom.[40]

There has been disagreement among historians on whether Sherman's March constituted total war.[41] In the years following World War II, several writers[42][43][44] argued that the total war tactics used during World War II were comparable to the tactics used during Sherman's March. Subsequent historians have objected to the comparison, arguing that Sherman's tactics were not as severe or indiscriminate.[45] Some historians refer to Sherman's tactics as "hard war" to emphasize the distinction between Sherman's tactics and those used during World War II.[46][47]

The "hard war" doctrine in Civil War historiography first appeared in quotes from Sherman's correspondence, specifically during the interim ten days between his March to the Sea and Carolinas campaign. He first distinguished between "this war" and "European wars in particular": Union soldiers were "not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies." Sherman acknowledged that "the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina. I almost tremble at her fate, but feel that she deserves all that seems in store for her." The general endeavored to assure southern Unionists in Georgia that he planned on applying the "hard hand of war" to the Carolinas in less than a week. According to the general, "the invariable reply was, 'Well, if you will make those people feel the utmost severities of war, we will pardon you for your desolation of Georgia.' I look upon Columbia as quite as bad as Charleston, and I doubt if we will spare the public buildings there as we did at Milledgeville."[48]

One example of an outspoken exponent of the "hard war" classification was W. Todd Groce, President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Georgia Historical Society. In his publications, Groce focused on the March to the Sea, contending that "it lacked the wholesale destruction of human life that characterized World War II" and that "Sherman's primary targets – foodstuffs and industrial, government and military property – were carefully chosen to create the desired effect, and never included mass killing of civilians." Groce premised his arguments on the notion that Sherman's Special Field Orders No. 120 (1864), which prohibited Union soldiers from entering Confederate dwellings and encouraged Union soldiers to appropriate Confederate horses, mules, and wagons only from "the rich", had successfully mitigated the effects of the previous year's Lieber Code. Groce summarized the latter code, signed into law by Lincoln on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, as authorizing the Union "Army to destroy civilian property, starve noncombatants, shell towns, keep enemy civilians in besieged cities, free slaves and summarily execute guerrillas if such measures were deemed necessary to winning the war and defending the country."[49]

The sole exception to Groce's focus on the March to the Sea was evidence for his contention that Sherman fought "to bring rebels back into the Union, not to annihilate them." Groce rested this corollary conclusion on a vignette from the Carolinas campaign. According to Groce, Sherman "told one South Carolina woman that he was ransacking her plantation so that her soldier husband would come home and Grant would not have to kill him in the trenches at Petersburg."[49]

In a 2014 review essay, historian Daniel E. Sutherland observed that "scholars who insist that 'total' wars must be defined by saturation bombing or the callous dismissal of dead civilians as collateral damage often seem eager to sanitize the American Civil War by making it appear less uncivil than it was in fact. They might consider, as Brady and Nelson [authors of two 2012 studies] have done, that absolute destruction and dislocation can take many forms and must ultimately be defined by the victims of war."[50] The historiographical debates between scorched earth "hard war"[51][52][53] proponents and "total war" mainstays threatened to overshadow studies on the ecological devastation wrought by, for example, the Valley Campaigns of 1864, or Union soldier violations of the " 'spatial and corporeal privacy' of Confederate women" during the Carolinas campaign.[50] Unverified estimates indicate that nine Confederate civilians died every 72 hours during Sherman's 37-day March to the Sea. Historians still consider this number comparatively low. There was, however, a "shift to hard war" in the ensuing Carolinas campaign, with mounting Confederate civilian fatalities matching a surge in the number of confirmed sexual assaults on Confederate women by male Union soldiers.[54][55][56][53]

During the South Carolina stage of the so-called "March North from the Sea",[57] historian Lisa Tendrich Frank maintained, Union soldiers had "earned a reputation for being 'rather loose on the handle.' " Sherman responded to the South Carolina increase in sexual assaults by punishing "the rape of white women, whose race and class provided some privileges and protections" in North Carolina. The records of Sherman's punitive actions in North Carolina revealed that punishments were commensurate with the conditions of Confederate rape victims, as well as the number of sexual assaults by a given perpetrator. For instance, one soldier " 'did by physical force and violence commit rape upon the person of one Miss Letitia Craft' in North Carolina", but the case was pending because the soldier may have been involved in the gang or serial rape of two additional Confederate women. As the Carolinas campaign continued, the racial contours of Sherman's disciplinary efforts shifted the targets of sexual assault from Confederate women to freedwomen because his men "rarely suffered consequences for their sexual assaults on African American women."[54]

Consequentialism and the Ovidian-Machiavellian aphorism, "the end justifies the means", played roles in Union military strategy. According to Sutherland, Union generals believed that, "however destructive Union military policy proved to be, the ends of repairing the Union and abolishing slavery justified the means. Grant, Sheridan, and Sherman all said as much." Historians who attempted to classify the Civil War as a "total war" or scorched-earth "hard war" confounded their own conceptual frameworks for the persistence of this consequentialist bellum, a thinly-veiled justification for racially-motivated hate crimes that largely spared Confederate noncombatants. During the Reconstruction era and post-bellum American Indian Wars, Civil War "relics lost the horror of their creation" and the war itself "acquired a nostalgic glow" for federal regiments and cavalry, even as "former Confederates exploited, and sometimes exaggerated, the destruction to enhance the power of their Lost Cause rhetoric."[50]

Conversely, for scholars who advanced an indiscriminate consequentialism against noncombatants, especially Confederate ones, as key to expediting abolition and winning the war, "why should we not simply acknowledge the circumstances, rather than be embarrassed by them or try to cloak them in euphemisms?"[50] In a 2017 book review, Sutherland added that "a more profitable approach to understanding why the war was fought with increasingly destructive force – and not just by Sherman – may be to recognize the fact that both armies waged, in Jefferson Davis's words, a 'savage war,' and accept it on those terms."[58] Sutherland had previously argued that both sides invoked a comparative ethno-racial "Indian savagery" in explanations for "the need for ruthlessness."[59]

Historians Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh and Williamson Murray likewise contended that "Sherman, and Grant, for that matter, were looking backward, not forward." Sherman studied the history of European warfare, "not to mention the actions of Americans fighting the Indians in North America." Sherman's soldiers torched expansive acreage owned by planters as well as entire civilian neighborhoods. Sherman's army "undoubtedly would have tossed [all] such owners into the fire", but a number of planters already decamped. The remaining civilians could, in many instances, "leave before their houses were torched." These "hard war" practices "were relatively rare in Georgia, but became more prevalent when Sherman's army reached South Carolina."[60]

More recently, historians have begun to research the extent to which Sherman's Special Orders No. 120 mitigated the effects of the Lieber Code during the March to the Sea, as well as questioning the practical execution of the latter code's strict dichotomy between civilians and combatants.[55] The Special Field Orders No. 120, for instance, indicated that, "should guerrillas or bushwhackers molest our march, or should the inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads, or otherwise manifest local hostility, then army commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or less relentless according to the measure of such hostility."[61] In a 2023 encyclopedia entry on irregular civilian, southern Unionist, and guerilla warfare in and by the Confederate States of America, historian Matthew Stith conceded that critics of "total war" usages in Civil War historiography were often "heavy-handed." In the final analysis, however, "debates about the war's severity—total versus hard—as well as the nature of guerrillas themselves—noble warriors or bloodthirsty criminals—beg for more attention, even if each side of each debate might consider the case closed." Such studies on "irregular warfare" exacerbated, but also reconfigured, challenges in counting civilians and counting combatants during the Civil War.[62]

See also

[edit]- The March: A Novel (2005 historical novel by E. L. Doctorow)

- Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 15

- Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 120

- Sherman's March (2007 documentary)

- Western Theater of the American Civil War

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c d Further information: "Savannah Campaign Union order of battle" (Official Records, Series I, Volume XLIV, pp. 19–25)

- ^ Further information: "Effective strength of the army in the field under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, November and December, 1864" (Official Records, Series I, Volume XLIV, p. 16)

- ^ Further information: "Abstract from return of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, Lieut. Gen. W.J. Hardee commanding, November 20, 1864" (Official Records, Series I, Volume XLIV, p. 874)

- ^ a b c Catton, pp. 415–16.

- ^ Hudson, Myles (2023). "Sherman's March to the Sea". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Glatthar, pp. 78–80

- ^ a b Lyftogt, Kenneth. "Byers, Samuel Hawkins Marshall". The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. University of Iowa Press Digital Editions. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Lucas 1976, pp. 80, 86.

- ^ Byers, Samuel H. M. (1864) "Sherman's March to the Sea" in Carman, Bliss et al., editors (1904) The World's Best Poetry, Volume VIII. National Spirit via bartleby.com. Accessed: February 21, 2023

- ^ Eicher, p. 739.

- ^ Trudeau, pp. 47–48, 51–55.

- ^ Trudeau, p. 52.

- ^ a b Barrett 1956, p. 25.

- ^ Glatthar, pp. 18–20, 33

- ^ Liddell Hart, pp. 236–237

- ^ Liddell Hart, p. 331

- ^ Glatthar, p. 15

- ^ Coffey, Walter. "The Civil War This Week: Oct 27–Nov 2, 1864". WalterCoffey.com. Wordpress. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Further information: "Savannah Campaign Confederate order of battle" (Official Records, Series I, Vol. XLIV, pp. 875–76)

- ^ Trudeau, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Trudeau, p. 45.

- ^ Nevin, p. 48.

- ^ Melton, p. 288.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 693.

- ^ Trudeau, p. 508.

- ^ Trudeau, p. 521.

- ^ Gates, Henry Lewis Jr. (January 7, 2013) "The Truth Behind '40 Acres and a Mule'" The Root Archived June 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Barrett 1956, p. 27.

- ^ Barrett 1956, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Lucas, Marion Brunson (1976). Sherman and the burning of Columbia. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-018-6. OCLC 2331311.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 793–94, 797–99, 831–35.

- ^ OR, Series I, Vol. XLIV, Part 1, p. 798.

- ^ Parten, Bennett (2017). "'Somewhere Toward Freedom': Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 101 (2): 115–46. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Campbell, p. 33.

- ^ Kennett, p. 309.

- ^ Hattaway and Jones, p. 655.

- ^ Eicher, p. 768.

- ^ Feigenbaum, James; Lee, James; Mezzanotti, Filippo (2022). "Capital Destruction and Economic Growth: The Effects of Sherman's March, 1850–1920". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 14 (4): 301–342. doi:10.1257/app.20200397. hdl:2144/27528. ISSN 1945-7782.

- ^ Eicher, p. 763.

- ^ "Historical markers illustrate overlooked stories", 5 September 2011; accessed 28 July 2016

- ^ Caudill, Edward and Ashdown, Paul (2008). Sherman's March in Myth and Memory. United States: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 75–79. ISBN 9781442201279.

- ^ Barrett, John G. (1960) "Sherman and Total War in the Carolinas". North Carolina Historical Review 37 (3): 367–81

- ^ Walters, John Bennett (1948) "General William T. Sherman and Total War". Journal of Southern History 14 (4): 447–80

- ^ Corwin, E. S. (1947) Total War and the Constitution. New York: Knopf.

- ^ Neeley, Mark E. Jr. (1991) "Was the Civil War a Total War?". Civil War History 37 (1): 5–28 [10.1353/cwh.2004.0073 online]

- ^ Grimsley, Mark (1995). The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780521462570.

- ^ Groce, W. Todd (November 17, 2014). "Rethinking Sherman's March". The New York Times.

- ^ "Letter of William T. Sherman to Henry Halleck, December 24, 1864". 24 December 1864.

- ^ a b Groce, W. Todd (18 November 2014). "Rethinking Sherman's March". Opinionator.

- ^ a b c d Sutherland, Daniel E. (2014). "Total War by Other Means". Reviews in American History. 42 (1): 97–103. doi:10.1353/rah.2014.0022. ISSN 0048-7511.

- ^ "Sherman's March to the Sea". 17 September 2014.

- ^ "The Burning (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ a b Frank, Lisa Tendrich (2015). The Civilian War: Confederate Women and Union Soldiers during Sherman's March. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-5997-2.

- ^ a b Frank, Lisa Tendrich (2019). "The Carolinas Campaign". The Cambridge History of the American Civil War: Volume 1: Military Affairs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 337–361. ISBN 978-1-107-14889-5.

- ^ a b Kinsella, Helen M. (2011). The Image before the Weapon: A Critical History of the Distinction between Combatant and Civilian. Cornell University Press. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-8014-6126-2.

- ^ McCURRY, Stephanie (2017). "Enemy Women and the Laws of War in the American Civil War". Law and History Review. 35 (3): 667–710. doi:10.1017/S0738248017000244. ISSN 0738-2480.

- ^ Campbell, Jacqueline Glass (2006). When Sherman Marched North from the Sea: Resistance on the Confederate Home Front. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-7679-4.

- ^ "Sutherland on Campbell, 'When Sherman Marched North from the Sea: Resistance on the Confederate Home Front' | H-Net". networks.h-net.org.

- ^ Sutherland, Daniel E. (2009). A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 26–40. ISBN 978-0-8078-3277-6.

- ^ Murray, Williamson; Hsieh, Wayne Wei-Siang (2018). A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War. Princeton University Press. pp. 467–468. ISBN 978-1-4008-8937-2.

- ^ "Avalon Project – General Orders No. 100 : The Lieber Code". avalon.law.yale.edu.

- ^ Stith, Matthew M. (31 January 2023). "Irregular and Guerrilla Warfare during the Civil War". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.926. ISBN 978-0-19-932917-5.

Bibliography

- Barrett, John Gilchrist (1956). Sherman's march through the Carolinas. Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-1-4696-1112-9. OCLC 864900203.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Campbell, Jacqueline Glass (2003) When Sherman Marched North from the Sea: Resistance on the Confederate Home Front. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5659-8.

- Catton, Bruce (1965) The Centennial History of the Civil War. Vol. 3, Never Call Retreat. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-671-46990-8.

- Eicher, David J. ( 2001) The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. (1995) [1985] The March to the Sea and Beyond: Sherman's Troops in the Savannah and Carolinas Campaigns. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2028-6.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 0-252-00918-5.

- Kennett, Lee (1995) Marching through Georgia: The Story of Soldiers and Civilians During Sherman's Campaign. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-092745-3.

- Liddell Hart, B. H. (1993) [1929] Sherman: Realist, Soldier, American. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80507-3

- McPherson, James M. (1988) Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Melton, Brian C. (2007) Sherman's Forgotten General. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1739-4.

- Nevin, David and the Editors of Time-Life Books (1986) Sherman's March: Atlanta to the Sea. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books ISBN 0-8094-4812-2.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. (2008) Southern Storm: Sherman's March to the Sea. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-059867-9.

- Primary sources

- Sherman, William T. Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman. 2nd ed. New York: Library of America, 1990. ISBN 0-940450-65-8. First published 1889 by D. Appleton & Co.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- "Savannah Campaign Union order of battle" (Official Records, Series I, Vol. XLIV, pp. 19–25

- "Savannah Campaign Confederate order of battle" (Official Records, Series I, Volume XLIV, pp. 875–876)

Further reading

- Davis, Burke, Sherman's March, Random House Publishing Group, 1980 / 2016. ISBN 978-1-5040-3441-8

- Davis, Stephen, What the Yankees Did to Us: Sherman's Bombardment and Wrecking of Atlanta. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2012. ISBN 0881463981

- Fowler, John D. and David B. Parker, eds. Breaking the Heartland: The Civil War in Georgia. 2011 ISBN 9780881462401

- Frank, Lisa Tendrich (2015). The Civilian War: Confederate Women and Union Soldiers During Sherman's March. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807159965. OCLC 894313641.

- Ludwick, Carol R; Rudy, Robert R. March to the Sea. Lexographic Press, 2022. ISBN 978-1-7345042-9-3

- Marszalek, John F. (2005). Sherman's March to the Sea. Texas: McWhiney Foundation Press.

- Miers, Earl Schenck. The General Who Marched to Hell; William Tecumseh Sherman and His March to Fame and Infamy. New York: Knopf, 1951. OCLC 1107192

- Miles, Jim. To the Sea: A History and Tour Guide of the War in the West, Sherman's March across Georgia and through the Carolinas, 1864–1865. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2002. ISBN 1-58182-261-8.

- Rhodes, James Ford. "Sherman's March to the Sea" American Historical Review 6#3 (1901) pp. 466–474 online free old classic account

- Rubin, Anne Sarah (2014). Through the Heart of Dixie : Sherman's March and American Memory. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469617770. OCLC 875742477.

- Secrist, Philip L., Sherman's 1864 Trail of Battle to Atlanta. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780865547452

- Smith, David, and Richard Hook. Sherman's March to the Sea 1864: Atlanta to Savannah Osprey Publishing, 2012. ISBN 9781846030352 OCLC 74968763

- Smith, Derek. Civil War Savannah. Savannah, Ga: Frederic C. Beil, 1997. ISBN 0-913720-93-3.

- Welch, Robert Christopher. "Forage Liberally: The Role of Agriculture in Sherman's March to the Sea." Iowa State University thesis, 2011. online

- Whelchel, Love Henry (2014). Sherman's March and the Emergence of the Independent Black Church Movement: From Atlanta to the Sea to Emancipation. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137405173. OCLC 864501780.

External links

[edit]- General Sherman's March to the Sea

- General Sherman's Surprise Christmas Present for President Lincoln at Slate

- Noah Andre Trudeau: Southern Storm at the Pritzker Military Museum & Library

- Photographic views of Sherman's campaign, from negatives taken in the field, by Geo. N. Barnard, official photographer of the military div. of the Mississippi. Published/Created: New York, Press of Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, 1866. (searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- Rethinking Sherman's March at The New York Times

- Sheet music for "Sherman's March to the Sea" from Project Gutenberg

- Sherman's March to the Sea

- When Georgia Howled: Sherman on the March on YouTube