Taxonomy

| Information science |

|---|

| General aspects |

| Related fields and subfields |

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme of classes (a taxonomy) and the allocation of things to the classes (classification).

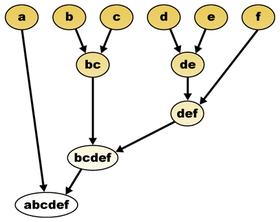

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. Among other things, a taxonomy can be used to organize and index knowledge (stored as documents, articles, videos, etc.), such as in the form of a library classification system, or a search engine taxonomy, so that users can more easily find the information they are searching for. Many taxonomies are hierarchies (and thus, have an intrinsic tree structure), but not all are.

Originally, taxonomy referred only to the categorisation of organisms or a particular categorisation of organisms. In a wider, more general sense, it may refer to a categorisation of things or concepts, as well as to the principles underlying such a categorisation. Taxonomy organizes taxonomic units known as "taxa" (singular "taxon")."

Taxonomy is different from meronomy, which deals with the categorisation of parts of a whole.

Etymology[edit]

The word was coined in 1813 by the Swiss botanist A. P. de Candolle and is irregularly compounded from the Greek τάξις, taxis 'order' and νόμος, nomos 'law', connected by the French form -o-; the regular form would be taxinomy, as used in the Greek reborrowing ταξινομία.[1][2]

Applications[edit]

Wikipedia categories form a taxonomy,[3] which can be extracted by automatic means.[4] As of 2009[update], it has been shown that a manually-constructed taxonomy, such as that of computational lexicons like WordNet, can be used to improve and restructure the Wikipedia category taxonomy.[5]

In a broader sense, taxonomy also applies to relationship schemes other than parent-child hierarchies, such as network structures. Taxonomies may then include a single child with multi-parents, for example, "Car" might appear with both parents "Vehicle" and "Steel Mechanisms"; to some however, this merely means that 'car' is a part of several different taxonomies.[6] A taxonomy might also simply be organization of kinds of things into groups, or an alphabetical list; here, however, the term vocabulary is more appropriate. In current usage within knowledge management, taxonomies are considered narrower than ontologies since ontologies apply a larger variety of relation types.[7]

Mathematically, a hierarchical taxonomy is a tree structure of classifications for a given set of objects. It is also named containment hierarchy. At the top of this structure is a single classification, the root node, that applies to all objects. Nodes below this root are more specific classifications that apply to subsets of the total set of classified objects. The progress of reasoning proceeds from the general to the more specific.

By contrast, in the context of legal terminology, an open-ended contextual taxonomy is employed—a taxonomy holding only with respect to a specific context. In scenarios taken from the legal domain, a formal account of the open-texture of legal terms is modeled, which suggests varying notions of the "core" and "penumbra" of the meanings of a concept. The progress of reasoning proceeds from the specific to the more general.[8]

History[edit]

Anthropologists have observed that taxonomies are generally embedded in local cultural and social systems, and serve various social functions. Perhaps the most well-known and influential study of folk taxonomies is Émile Durkheim's The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. A more recent treatment of folk taxonomies (including the results of several decades of empirical research) and the discussion of their relation to the scientific taxonomy can be found in Scott Atran's Cognitive Foundations of Natural History. Folk taxonomies of organisms have been found in large part to agree with scientific classification, at least for the larger and more obvious species, which means that it is not the case that folk taxonomies are based purely on utilitarian characteristics.[9]

In the seventeenth century the German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz, following the work of the thirteenth-century Majorcan philosopher Ramon Llull on his Ars generalis ultima, a system for procedurally generating concepts by combining a fixed set of ideas, sought to develop an alphabet of human thought. Leibniz intended his characteristica universalis to be an "algebra" capable of expressing all conceptual thought. The concept of creating such a "universal language" was frequently examined in the 17th century, also notably by the English philosopher John Wilkins in his work An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (1668), from which the classification scheme in Roget's Thesaurus ultimately derives.

Taxonomy in various disciplines[edit]

Natural sciences[edit]

Taxonomy in biology encompasses the description, identification, nomenclature, and classification of organisms. Uses of taxonomy include:

- Alpha taxonomy, the description and basic classification of new species, subspecies, and other taxa

- Linnaean taxonomy, the original classification scheme of Carl Linnaeus

- rank-based scientific classification as opposed to clade-based classification

- Evolutionary taxonomy, traditional post-Darwinian hierarchical biological classification

- Numerical taxonomy, various taxonomic methods employing numeric algorithms

- Phenetics, system for ordering species based on overall similarity

- Phylogenetics, biological taxonomy based on putative ancestral descent of organisms

- Plant taxonomy

- Virus classification, taxonomic system for viruses

- Folk taxonomy, description and organization, by individuals or groups, of their own environments

- Nosology, classification of diseases

- Soil classification, systematic categorization of soils

Business and economics[edit]

Uses of taxonomy in business and economics include:

- Corporate taxonomy, the hierarchical classification of entities of interest to an enterprise, organization or administration

- Economic taxonomy, a system of classification for economic activity

- Global Industry Classification Standard, an industry taxonomy developed by MSCI and Standard & Poor's (S&P)

- Industry Classification Benchmark, an industry classification taxonomy launched by Dow Jones and FTSE

- International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC), a United Nations system for classifying economic data

- North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), used in Canada, Mexico, and the United States of America

- Pavitt's Taxonomy, classification of firms by their principal sources of innovation

- Standard Industrial Classification, a system for classifying industries by a four-digit code

- United Kingdom Standard Industrial Classification of Economic Activities, a Standard Industrial Classification by type of economic activity

- EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, a classification system established to clarify which investments are environmentally sustainable, in the context of the European Green Deal.

- Records management taxonomy, the representation of data, upon which the classification of unstructured content is based, within an organization.

- XBRL Taxonomy, eXtensible Business Reporting Language

- SRK taxonomy, in workplace user-interface design

Computing[edit]

Software engineering[edit]

Vegas et al.[10] make a compelling case to advance the knowledge in the field of software engineering through the use of taxonomies. Similarly, Ore et al.[11] provide a systematic methodology to approach taxonomy building in software engineering related topics.

Several taxonomies have been proposed in software testing research to classify techniques, tools, concepts and artifacts. The following are some example taxonomies:

Engström et al.[14] suggest and evaluate the use of a taxonomy to bridge the communication between researchers and practitioners engaged in the area of software testing. They have also developed a web-based tool[15] to facilitate and encourage the use of the taxonomy. The tool and its source code are available for public use.[16]

Other uses of taxonomy in computing[edit]

- Flynn's taxonomy, a classification for instruction-level parallelism methods

- Folksonomy, classification based on user's tags

- Taxonomy for search engines, considered as a tool to improve relevance of search within a vertical domain

- ACM Computing Classification System, a subject classification system for computing devised by the Association for Computing Machinery

Education and academia[edit]

Uses of taxonomy in education include:

- Bloom's taxonomy, a standardized categorization of learning objectives in an educational context

- Classification of Instructional Programs, a taxonomy of academic disciplines at institutions of higher education in the United States

- Mathematics Subject Classification, an alphanumerical classification scheme based on the coverage of Mathematical Reviews and Zentralblatt MATH

- SOLO taxonomy, Structure of Observed Learning Outcome, proposed by Biggs and Collis Tax

Safety[edit]

Uses of taxonomy in safety include:

- Safety taxonomy, a standardized set of terminologies used within the fields of safety and health care

- Human Factors Analysis and Classification System, a system to identify the human causes of an accident

- Swiss cheese model, a model used in risk analysis and risk management propounded by Dante Orlandella and James T. Reason

- A taxonomy of rail incidents in Confidential Incident Reporting & Analysis System (CIRAS)

Other taxonomies[edit]

- Military taxonomy, a set of terms that describe various types of military operations and equipment

- Moys Classification Scheme, a subject classification for law devised by Elizabeth Moys

Research publishing[edit]

Citing inadequacies with current practices in listing authors of papers in medical research journals, Drummond Rennie and co-authors called in a 1997 article in JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association for

a radical conceptual and systematic change, to reflect the realities of multiple authorship and to buttress accountability. We propose dropping the outmoded notion of author in favor of the more useful and realistic one of contributor.[17]: 152

Since 2012, several major academic and scientific publishing bodies have mounted Project CRediT to develop a controlled vocabulary of contributor roles.[18] Known as CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy), this is an example of a flat, non-hierarchical taxonomy; however, it does include an optional, broad classification of the degree of contribution: lead, equal or supporting. Amy Brand and co-authors summarise their intended outcome as:

Identifying specific contributions to published research will lead to appropriate credit, fewer author disputes, and fewer disincentives to collaboration and the sharing of data and code.[17]: 151

As of mid-2018, this taxonomy apparently restricts its scope to research outputs, specifically journal articles; however, it does rather unusually "hope to … support identification of peer reviewers".[18] (As such, it has not yet defined terms for such roles as editor or author of a chapter in a book of research results.) Version 1, established by the first Working Group in the (northern) autumn of 2014, identifies 14 specific contributor roles using the following defined terms:

- Conceptualization

- Methodology

- Software

- Validation

- Formal Analysis

- Investigation

- Resources

- Data curation

- Writing – Original Draft

- Writing – Review & Editing

- Visualization

- Supervision

- Project Administration

- Funding acquisition

Reception has been mixed, with several major publishers and journals planning to have implemented CRediT by the end of 2018, whilst almost as many are not persuaded of the need or value of using it. For example,

The National Academy of Sciences has created a TACS (Transparency in Author Contributions in Science) webpage to list the journals that commit to setting authorship standards, defining responsibilities for corresponding authors, requiring ORCID iDs, and adopting the CRediT taxonomy.[19]

The same webpage has a table listing 21 journals (or families of journals), of which:

- 5 have, or by end 2018 will have, implemented CRediT,

- 6 require an author contribution statement and suggest using CRediT,

- 8 do not use CRediT, of which 3 give reasons for not doing so, and

- 2 are uninformative.

The taxonomy is an open standard conforming to the OpenStand principles,[20] and is published under a Creative Commons licence.[18]

Taxonomy for the web[edit]

Websites with a well designed taxonomy or hierarchy are easily understood by users, due to the possibility of users developing a mental model of the site structure.[21]

Guidelines for writing taxonomy for the web include:

- Mutually exclusive categories can be beneficial. If categories appear in several places, it is called cross-listing or polyhierarchical. The hierarchy will lose its value if cross-listing appears too often. Cross-listing often appears when working with ambiguous categories that fits more than one place.[21]

- Having a balance between breadth and depth in the taxonomy is beneficial. Too many options (breadth), will overload the users by giving them too many choices. At the same time having a too narrow structure, with more than two or three levels to click-through, will make users frustrated and might give up.[21]

In communications theory[edit]

Frederick Suppe[22] distinguished two senses of classification: a broad meaning, which he called "conceptual classification" and a narrow meaning, which he called "systematic classification".

About conceptual classification Suppe wrote:[22]: 292 "Classification is intrinsic to the use of language, hence to most if not all communication. Whenever we use nominative phrases we are classifying the designated subject as being importantly similar to other entities bearing the same designation; that is, we classify them together. Similarly the use of predicative phrases classifies actions or properties as being of a particular kind. We call this conceptual classification, since it refers to the classification involved in conceptualizing our experiences and surroundings"

About systematic classification Suppe wrote:[22]: 292 "A second, narrower sense of classification is the systematic classification involved in the design and utilization of taxonomic schemes such as the biological classification of animals and plants by genus and species.

Is-a and has-a relationships, and hyponymy[edit]

Two of the predominant types of relationships in knowledge-representation systems are predication and the universally quantified conditional. Predication relationships express the notion that an individual entity is an example of a certain type (for example, John is a bachelor), while universally quantified conditionals express the notion that a type is a subtype of another type (for example, "A dog is a mammal", which means the same as "All dogs are mammals").[23]

The "has-a" relationship is quite different: an elephant has a trunk; a trunk is a part, not a subtype of elephant. The study of part-whole relationships is mereology.

Taxonomies are often represented as is-a hierarchies where each level is more specific than the level above it (in mathematical language is "a subset of" the level above). For example, a basic biology taxonomy would have concepts such as mammal, which is a subset of animal, and dogs and cats, which are subsets of mammal. This kind of taxonomy is called an is-a model because the specific objects are considered as instances of a concept. For example, Fido is-an instance of the concept dog and Fluffy is-a cat.[24]

In linguistics, is-a relations are called hyponymy. When one word describes a category, but another describe some subset of that category, the larger term is called a hypernym with respect to the smaller, and the smaller is called a "hyponym" with respect to the larger. Such a hyponym, in turn, may have further subcategories for which it is a hypernym. In the simple biology example, dog is a hypernym with respect to its subcategory collie, which in turn is a hypernym with respect to Fido which is one of its hyponyms. Typically, however, hypernym is used to refer to subcategories rather than single individuals.

Research[edit]

Researchers reported that large populations consistently develop highly similar category systems. This may be relevant to lexical aspects of large communication networks and cultures such as folksonomies and language or human communication, and sense-making in general.[25][26]

Theoretical approaches[edit]

Knowledge organization[edit]

Hull (1998) suggested "The fundamental elements of any classification are its theoretical commitments, basic units and the criteria for ordering these basic units into a classification".[27]

There is a widespread opinion in knowledge organization and related fields that such classes corresponds to concepts. We can, for example, classify "waterfowls" into the classes "ducks", "geese", and "swans"; we can also say, however, that the concept “waterfowl” is a generic broader term in relation to the concepts "ducks", "geese", and "swans". This example demonstrates the close relationship between classification theory and concept theory. A main opponent of concepts as units is Barry Smith.[28] Arp, Smith and Spear (2015) discuss ontologies and criticize the conceptualist understanding.[29]: 5ff The book writes (7): “The code assigned to France, for example, is ISO 3166 – 2:FR and the code is assigned to France itself — to the country that is otherwise referred to as Frankreich or Ranska. It is not assigned to the concept of France (whatever that might be).” Smith's alternative to concepts as units is based on a realist orientation, when scientists make successful claims about the types of entities that exist in reality, they are referring to objectively existing entities which realist philosophers call universals or natural kinds. Smith's main argument - with which many followers of the concept theory agree - seems to be that classes cannot be determined by introspective methods, but must be based on scientific and scholarly research. Whether units are called concepts or universals, the problem is to decide when a thing (say a "blackbird") should be considered a natural class. In the case of blackbirds, for example, recent DNA analysis have reconsidered the concept (or universal) "blackbird" and found that what was formerly considered one species (with subspecies) are in reality many different species, which just have chosen similar characteristics to adopt to their ecological niches.[30]: 141

An important argument for considering concepts the basis of classification is that concepts are subject to change and that they changes when scientific revolutions occur. Our concepts of many birds, for example, have changed with recent development in DNA analysis and the influence of the cladistic paradigm - and have demanded new classifications. Smith's example of France demands an explanation. First, France is not a general concept, but an individual concept. Next, the legal definition of France is determined by the conventions that France has made with other countries. It is still a concept, however, as Leclercq (1978) demonstrates with the corresponding concept Europe.[31]

Hull (1998) continued:[27] "Two fundamentally different sorts of classification are those that reflect structural organization and those that are systematically related to historical development." What is referred to is that in biological classification the anatomical traits of organisms is one kind of classification, the classification in relation to the evolution of species is another (in the section below, we expand these two fundamental sorts of classification to four). Hull adds that in biological classification, evolution supplies the theoretical orientation.[27]

Ereshevsky[edit]

Ereshefsky (2000) presented and discussed three general philosophical schools of classification: "essentialism, cluster analysis, and historical classification. Essentialism sorts entities according to causal relations rather than their intrinsic qualitative features."[32]

These three categories may, however, be considered parts of broader philosophies. Four main approaches to classification may be distinguished: (1) logical and rationalist approaches including "essentialism"; (2) empiricist approaches including cluster analysis (It is important to notice that empiricism is not the same as empirical study, but a certain ideal of doing empirical studies. With the exception of the logical approaches they all are based on empirical studies, but are basing their studies on different philosophical principles). (3) Historical and hermeneutical approaches including Ereshefsky's "historical classification" and (4) Pragmatic, functionalist and teleological approaches (not covered by Ereshefsky). In addition there are combined approaches (e.g., the so-called evolutionary taxonomy", which mixes historical and empiricist principles).

Logical and rationalist approaches[edit]

Logical division[33] (top-down classification or downward classification) is an approach that divides a class into subclasses and then divide subclasses into their subclasses, and so on, which finally forms a tree of classes. The root of the tree is the original class, and the leaves of the tree are the final classes. Plato advocated a method based on dichotomy, which was rejected by Aristotle and replaced by the method of definitions based on genus, species, and specific difference.[34] The method of facet analysis (cf., faceted classification) is primarily based on logical division.[35] This approach tends to classify according to "essential" characteristics, a widely discussed and criticized concept (cf., essentialism). These methods may overall be related to the rationalist theory of knowledge.

Empiricist approaches[edit]

"Empiricism alone is not enough: a healthy advance in taxonomy depends on a sound theoretical foundation"[36]: 548

Phenetics or numerical taxonomy[37] is by contrast bottom-up classification, where the starting point is a set of items or individuals, which are classified by putting those with shared characteristics as members of a narrow class and proceeding upward. Numerical taxonomy is an approach based solely on observable, measurable similarities and differences of the things to be classified. Classification is based on overall similarity: The elements that are most alike in most attributes are classified together. But it is based on statistics, and therefore does not fulfill the criteria of logical division (e.g. to produce classes, that are mutually exclusive and jointly coextensive with the class they divide). Some people will argue that this is not classification/taxonomy at all, but such an argument must consider the definitions of classification (see above). These methods may overall be related to the empiricist theory of knowledge.

Historical and hermeneutical approaches[edit]

Genealogical classification is classification of items according to their common heritage. This must also be done on the basis of some empirical characteristics, but these characteristics are developed by the theory of evolution. Charles Darwin's[38] main contribution to classification theory of not just his claim "... all true classification is genealogical ..." but that he provided operational guidance for classification.[39]: 90–92 Genealogical classification is not restricted to biology, but is also much used in, for example, classification of languages, and may be considered a general approach to classification." These methods may overall be related to the historicist theory of knowledge. One of the main schools of historical classification is cladistics, which is today dominant in biological taxonomy, but also applied to other domains.

The historical and hermeneutical approaches is not restricted to the development of the object of classification (e.g., animal species) but is also concerned with the subject of classification (the classifiers) and their embeddedness in scientific traditions and other human cultures.

Pragmatic, functionalist and teleological approaches[edit]

Pragmatic classification (and functional[40] and teleological classification) is the classification of items which emphasis the goals, purposes, consequences,[41] interests, values and politics of classification. It is, for example, classifying animals into wild animals, pests, domesticated animals and pets. Also kitchenware (tools, utensils, appliances, dishes, and cookware used in food preparation, or the serving of food) is an example of a classification which is not based on any of the above-mentioned three methods, but clearly on pragmatic or functional criteria. Bonaccorsi, et al. (2019) is about the general theory of functional classification and applications of this approach for patent classification.[40] Although the examples may suggest that pragmatic classifications are primitive compared to established scientific classifications, it must be considered in relation to the pragmatic and critical theory of knowledge, which consider all knowledge as influences by interests.[42] Ridley (1986) wrote:[43]: 191 "teleological classification. Classification of groups by their shared purposes, or functions, in life - where purpose can be identified with adaptation. An imperfectly worked-out, occasionally suggested, theoretically possible principle of classification that differs from the two main such principles, phenetic and phylogenetic classification".

Artificial versus natural classification[edit]

Natural classification is a concept closely related to the concept natural kind. Carl Linnaeus is often recognized as the first scholar to clearly have differentiated "artificial" and "natural" classifications[44][45] A natural classification is one, using Plato's metaphor, that is “carving nature at its joints”[46] Although Linnaeus considered natural classification the ideal, he recognized that his own system (at least partly) represented an artificial classification.

John Stuart Mill explained the artificial nature of the Linnaean classification and suggested the following definition of a natural classification:

"The Linnæan arrangement answers the purpose of making us think together of all those kinds of plants, which possess the same number of stamens and pistils; but to think of them in that manner is of little use, since we seldom have anything to affirm in common of the plants which have a given number of stamens and pistils."[21]: 498 "The ends of scientific classification are best answered, when the objects are formed into groups respecting which a greater number of general propositions can be made, and those propositions more important, than could be made respecting any other groups into which the same things could be distributed."[21]: 499 "A classification thus formed is properly scientific or philosophical, and is commonly called a Natural, in contradistinction to a Technical or Artificial, classification or arrangement."[21]: 499

Ridley (1986) provided the following definitions:[43]

- "artificial classification. The term (like its opposite, natural classification) has many meanings; in this book I have picked a phenetic meaning. A classificatory group will be defined by certain characters, called defining characters; in an artificial classification, the members of a group resemble one another in their defining characters (as they must, by definition) but not in their non-defining characters. With respect to the characters not used in the classification, the members of a group are uncorrelated.

- "natural classification. Classificatory groups are defined by certain characters, called 'defining' characters; in a natural group, the members of the group resemble one another for non-defining characters as well as for the defining character. This is not the only meaning for what is perhaps the most variously used term in taxonomy ...

Taxonomic monism vs. pluralism[edit]

Stamos (2004)[47]: 138 wrote: "The fact is, modern scientists classify atoms into elements based on proton number rather than anything else because it alone is the causally privileged factor [gold is atomic number 79 in the periodic table because it has 79 protons in its nucleus]. Thus nature itself has supplied the causal monistic essentialism. Scientists in their turn simply discover and follow (where "simply" ≠ "easily")."

Examples of important taxonomies[edit]

Periodic table[edit]

The periodic table is the classification of the chemical elements which is in particular associated with Dmitri Mendeleev (cf., History of the periodic table). An authoritative work on this system is Scerri (2020).[48] Hubert Feger (2001; numbered listing added) wrote about it:[49]: 1967–1968 "A well-known, still used, and expanding classification is Mendeleev's Table of Elements. It can be viewed as a prototype of all taxonomies in that it satisfies the following evaluative criteria:

- Theoretical foundation: A theory determines the classes and their order.

- Objectivity: The elements can be observed and classified by anybody familiar with the table of elements.

- Completeness: All elements find a unique place in the system, and the system implies a list of all possible elements.

- Simplicity: Only a small amount of information is used to establish the system and identify an object.

- Predictions: The values of variables not used for classification can be predicted (number of electrons and atomic weight), as well as the existence of relations and of objects hitherto unobserved. Thus, the validity of the classification system itself becomes testable."

Bursten (2020) wrote, however "Hepler-Smith, a historian of chemistry, and I, a philosopher whose work often draws on chemistry, found common ground in a shared frustration with our disciplines’ emphases on the chemical elements as the stereotypical example of a natural kind. The frustration we shared was that while the elements did display many hallmarks of paradigmatic kindhood, elements were not the kinds of kinds that generated interesting challenges for classification in chemistry, nor even were they the kinds of kinds that occupied much contemporary critical chemical thought. Compounds, complexes, reaction pathways, substrates, solutions – these were the kinds of the chemistry laboratory, and rarely if ever did they slot neatly into taxonomies in the orderly manner of classification suggested by the Periodic Table of Elements. A focus on the rational and historical basis of the development of the Periodic Table had made the received view of chemical classification appear far more pristine, and far less interesting, than either of us believed it to be."[50]

Linnaean taxonomy[edit]

Linnaean taxonomy is the particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his Systema Naturae (1735) and subsequent works. A major discussion in the scientific literature is whether a system that was constructed before Charles Darwin's theory of evolution can still be fruitful and reflect the development of life.[51][52]

Astronomy[edit]

Astronomy is a fine example on how Kuhn's (1962) theory of scientific revolutions (or paradigm shifts) influences classification.[53] For example:

- Paradigm one: Ptolemaic astronomers might learn the concepts "star" and "planet" by having the Sun, the Moon, and Mars pointed out as instances of the concept “planet” and some fixed stars as instances of the concept “star.”

- Paradigm two: Copernicans might learn the concepts "star", "planet", and "satellites" by having Mars and Jupiter pointed out as instances of the concept “planet,” the Moon as an instance of the concept “satellite,” and the Sun and some fixed stars as instances of the concept "star". Thus, the concepts "star", "planet", and "satellite" got a new meaning and astronomy got a new classification of celestial bodies.

Hornbostel–Sachs classification of musical instruments[edit]

Hornbostel–Sachs is a system of musical instrument classification devised by Erich Moritz von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs, and first published in 1914.[54] In the original classification, the top categories are:

- Idiophones: instruments that rely on the body of the instrument to create and resonate sound.

- Membranophones: instruments that have a membrane that is stretched over a structure, often wood or metal, and struck or rubbed to produce a sound. The subcategories are largely determined by the shape of the structure that the membrane is stretched over.

- Chordophone: Instruments that use vibrating strings, which are most commonly stretched across a metal or wooden structure, to create sound.

- Aerophones Instruments that require air passing through, or across, them to create sound. Most commonly constructed of wood or metal.

A fifth top category,

- Electrophones: Instruments that require electricity to be amplified and heard. This group was added by Sachs in 1940.

Each top category is subdivided and Hornbostel-Sachs is a very comprehensive classification of musical instruments with wide applications. In Wikipedia, for example, all musical instruments are organized according to this classification.

In opposition to, for example, the astronomical and biological classifications presented above, the Hornbostel-Sachs classification seems very little influenced by research in musicology and organology. It is based on huge collections of musical instruments, but seems rather as a system imposed upon the universe of instruments than as a system with organic connections to scholarly theory. It may therefore be interpreted as a system based on logical division and rationalist philosophy.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)[edit]

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a classification of mental disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).The first edition of the DSM was published in 1952,[55] and the newest, fifth edition was published in 2013.[56] In contrast to, for example, the periodic table and the Hornbostel-Sachs classification, the principles for classification have changed much during its history. The first edition was influenced by psychodynamic theory, The DSM-III, published in 1980[57] adopted an atheoretical, “descriptive” approach to classification[58] The system is very important for all people involved in psychiatry, whether as patients, researchers or therapists (in addition to insurance companies), but the systems is strongly criticized and has not the scientific status as many other classifications.[59]

Sample list of taxonomies[edit]

Business, organizations, and economics[edit]

- Classification of customers, for marketing (as in Master data management) or for profitability (e.g. by Activity-based costing)

- Classified information, as in legal or government documentation

- Job classification, as in job analysis

- Standard Industrial Classification, economic activities

Mathematics[edit]

- Attribute-value system, a basic knowledge representation framework

- Classification theorems in mathematics

- Mathematical classification, grouping mathematical objects based on a property that all those objects share

- Statistical classification, identifying to which of a set of categories a new observation belongs, on the basis of a training set of data

Media[edit]

- Classification (literature), a figure of speech linking a proper noun to a common noun using the or other articles

- Decimal classification, decimal classification systems

- Document classification, a problem in library science, information science and computer science

- Classified information, sensitive information to which access is restricted by law or regulation to particular classes of people

- Library classification, a system of coding, assorting and organizing library materials according to their subject

- Image classification in computer vision

- Motion picture rating system, for film classification

Science[edit]

- Scientific classification (disambiguation)

- Biological classification of organisms

- Chemical classification

- Medical classification, the process of transforming descriptions of medical diagnoses and procedures into universal medical code numbers

- Taxonomic classification, also known as classification of species

- Cladistics, an approach using similarities

Other[edit]

- An industrial process such as mechanical screening for sorting materials by size, shape, density, etc.

- Civil service classification, personnel grades in government

- Classification of swords

- Classification of wine

- Locomotive classification

- Product classification

- Security classification, information to which access is restricted by law or regulation

- Ship classification society, a non-governmental organization that establishes and maintains technical standards for the construction and operation of ships and offshore structures

Organizations involved in taxonomy[edit]

See also[edit]

- All pages with titles containing Taxonomy

The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary The dictionary definition of classification scheme at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of classification scheme at Wiktionary- Categorization, the process of dividing things into groups

- Classification (general theory)

- Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Recognition, a fictional Chinese encyclopedia with an "impossible" taxonomic scheme

- Conflation

- Faceted classification

- Folksonomy

- Gellish English dictionary, a taxonomy in which the concepts are arranged as a subtype–supertype hierarchy

- Hypernym

- Knowledge representation

- Lexicon

- Ontology (information science), formal representation of knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain

- Philosophical language

- Protégé (software)

- Semantic network

- Semantic similarity network

- Structuralism

- Systematics

- Taxon, a population of organisms that a taxonomist adjudges to be a unit

- Taxonomy for search engines

- Thesaurus (information retrieval)

- Typology (disambiguation)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1910. (partially updated December 2021), s.v.

- ^ review of Aperçus de Taxinomie Générale in Nature 60:489–490 Archived 2023-01-26 at the Wayback Machine (1899)

- ^ Zirn, Cäcilia, Vivi Nastase and Michael Strube. 2008. "Distinguishing Between Instances and Classes in the Wikipedia Taxonomy" (video lecture). Archived 2019-12-20 at the Wayback Machine 5th Annual European Semantic Web Conference (ESWC 2008).

- ^ S. Ponzetto and M. Strube. 2007. "Deriving a large scale taxonomy from Wikipedia" Archived 2017-08-14 at the Wayback Machine. Proc. of the 22nd Conference on the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, pp. 1440–1445.

- ^ S. Ponzetto, R. Navigli. 2009. "Large-Scale Taxonomy Mapping for Restructuring and Integrating Wikipedia". Proc. of the 21st International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2009), Pasadena, California, pp. 2083–2088.

- ^ Jackson, Joab. "Taxonomy's not just design, it's an art," Archived 2020-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Government Computer News (Washington, D.C.). September 2, 2004.

- ^ Suryanto, Hendra and Paul Compton. "Learning classification taxonomies from a classification knowledge based system." Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine University of Karlsruhe; "Defining 'Taxonomy'," Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine Straights Knowledge website.

- ^ Grossi, Davide, Frank Dignum and John-Jules Charles Meyer. (2005). "Contextual Taxonomies" in Computational Logic in Multi-Agent Systems, pp. 33–51[dead link].

- ^ Kenneth Boulding; Elias Khalil (2002). Evolution, Order and Complexity. Routledge. ISBN 9780203013151. p. 9

- ^ Vegas, S. (2009). "Maturing software engineering knowledge through classifications: A case study on unit testing techniques". IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 35 (4): 551–565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.221.7589. doi:10.1109/TSE.2009.13. S2CID 574495.

- ^ Ore, S. (2014). "Critical success factors taxonomy for software process deployment". Software Quality Journal. 22 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1007/s11219-012-9190-y. S2CID 18047921.

- ^ Utting, Mark (2012). "A taxonomy of model-based testing approaches". Software Testing, Verification & Reliability. 22 (5): 297–312. doi:10.1002/stvr.456. S2CID 6782211. Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- ^ Novak, Jernej (May 2010). "Taxonomy of static code analysis tools". Proceedings of the 33rd International Convention MIPRO: 418–422. Archived from the original on 2022-06-27. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ Engström, Emelie (2016). "SERP-test: a taxonomy for supporting industry–academia communication". Software Quality Journal. 25 (4): 1269–1305. doi:10.1007/s11219-016-9322-x. S2CID 34795073.

- ^ "SERP-connect". Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ Engstrom, Emelie (4 December 2019). "SERP-connect backend". GitHub. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ a b Brand, Amy; Allen, Liz; Altman, Micah; Hlava, Marjorie; Scott, Jo (1 April 2015). "Beyond authorship: attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit". Learned Publishing. 28 (2): 151–155. doi:10.1087/20150211. S2CID 45167271.

- ^ a b c "CRediT". CASRAI. CASRAI. 2 May 2018. Archived from the original (online) on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Transparency in Author Contributions in Science (TACS)" (online). National Academy of Sciences. 2018. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "OpenStand". OpenStand. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Peter., Morville (2007). Information architecture for the World Wide Web. Rosenfeld, Louis., Rosenfeld, Louis. (3rd ed.). Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly. ISBN 9780596527341. OCLC 86110226. Cite error: The named reference "Morville-2007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Suppe, Frederick. 1989. "Classification". In Erik Barnouw ed., International encyclopedia of communications. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, 292-296

- ^ Ronald J. Brachman; What IS-A is and isn't. An Analysis of Taxonomic Links in Semantic Networks Archived 2020-06-30 at the Wayback Machine. IEEE Computer, 16 (10); October 1983.

- ^ Brachman, Ronald (October 1983). "What IS-A is and isn't. An Analysis of Taxonomic Links in Semantic Networks". IEEE Computer. 16 (10): 30–36. doi:10.1109/MC.1983.1654194. S2CID 16650410.

- ^ "Why independent cultures think alike when it comes to categories: It's not in the brain". phys.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Guilbeault, Douglas; Baronchelli, Andrea; Centola, Damon (12 January 2021). "Experimental evidence for scale-induced category convergence across populations". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 327. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..327G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20037-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7804416. PMID 33436581.

Available under CC BY 4.0 Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Available under CC BY 4.0 Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Hull, David L. 1998. “Taxonomy.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward Craig. London: Routledge 9: 272-76.

- ^ Smith, Barry (2004). Varzi, Achille C.; Vieu, Laure (eds.). "Beyond Concepts: Ontology as Reality Representation". Amsterdam: IOS Press. In Proceedings of FOIS 2004. International Conference on Formal Ontology and Information Systems, Turin, 4–6 November 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Arp, Robert, Barry Smith and Andrew D Spear. 2015. Building Ontologies with Basic Formal Ontology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- ^ Fjeldså, Jon. 2013. “Avian Classification in Flux”. In Handbook of the Birds of the World. Special volume 17 Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 77-146 + references 493-501.

- ^ Leclercq, H. 1978. "Europe: Term for many Concepts. International Classification 5, no. 3: 156-162

- ^ Ereshefsky, Marc. 2000. The Poverty of the Linnaean Hierarchy: A Philosophical Study of Biological Taxonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Parry, William T. and Edward A. Hacker. 1991. Aristotelian logic. New York, NY: State University of New York Press, pp. 136-137

- ^ Pellegrin, Pierre. 1986. Aristotle's Classification of Animals: Biology and the Conceptual Unity of the Aristotelian Corpus. Translated by Anthony Preus. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Mills, Jack. 2004. "Faceted classification and logical division in information retrieval". Library Trends, 52(3), 541-570.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (9 November 1968). "Theory of Biological Classification". Nature. 220 (5167): 545–548. Bibcode:1968Natur.220..545M. doi:10.1038/220545a0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 5686724. S2CID 4225616. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Sokal , Robert R. and Peter H. A. Sneath 1963 . Principles of Numerical Taxonomy. San Francisco : W. H. Freeman and Company .

- ^ Darwin, Charles. 1859. On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: J. Murray.

- ^ Richards, Richard A. (2016). Biological Classification: A Philosophical Introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Bonaccorsi, Andres, Gualtiero Fantoni, Riccardo Apreda and Donata Gabelloni. 2019. “Functional Patent Classification”. In Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators, eds. Wolfgang Glänzel, Henk F. Moed, Ulrich Schmoch and Mike Thelwall. Cham, Switzerland : Springer, Chapter 40: 983-1003.

- ^ Bowker, Geoffrey C. and Susan Leigh Star. 1999. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- ^ Barnes, Barry. 1977. Interests and the Growth of Knowledge. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

- ^ a b Ridley, Mark. 1986. Evolution and Classification: The Reformation of Cladism. London: Longman.

- ^ Müller-Wille, Staffan. 2007. "Collection and collation: Theory and practice of Linnaean botany". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38, no. 3: 541-562.

- ^ Müller-Wille, Staffan. 2013. "Systems and how Linnaeus looked at them in retrospect". Annals of Science 3: 305-317.

- ^ Plato. c.370 BC. Phaedrus. (Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff eds.). Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing Co, Inc., 1995.

- ^ Stamos, David N. 2004. "Book Review of Discovery and Decision: Exploring the Metaphysics and Epistemology of Scientific Classification". Philosophical Psychology 17, no. 1: 135-9

- ^ Scerri. Eric. 2020. The Periodic Table: Its Story and Significance. Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press

- ^ Feger, Hubert. 2001. Classification: Conceptions in the social sciences. In Smelser, Neil J. and Baltes, Paul B. eds., International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences. New York: Elsevier, pp. 1966-73.

- ^ Bursten, Julia, R. S. 2020. "Introduction". In Perspectives on Classification in Synthetic Sciences: Unnatural Kinds, ed. Julia R. S. Bursten. London: Routledge

- ^ Weinstock, John. 1985. Contemporary Perspectives on Linnaeus. Lanham, MD: University Press of America

- ^ Ereshefsky Marc. 2001. The poverty of the Linnaean hierarchy: a philosophical study of biological taxonomy. Cambridge (Mass.): Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Hornbostel, Erich M. von and Curt Sachs. 1914. “Systematik der Musikinstrumente: Ein Versuch”. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie: Organ der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 46: 553-590.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. 1952. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (Fifth edition). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. 1980. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (3rd edition). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ Hjørland, Birger. 2016. “The Paradox of Atheoretical Classification.” Knowledge Organization 43: 313-323.

- ^ Cooper, Rachel. 2017. “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)”. Knowledge Organization 44, no. 8: 668-76.

References[edit]

- Atran, S. (1993) Cognitive Foundations of Natural History: Towards an Anthropology of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43871-1

- Carbonell, J. G. and J. Siekmann, eds. (2005). Computational Logic in Multi-Agent Systems, Vol. 3487. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.ISBN 978-3-540-28060-6

- Malone, Joseph L. (1988). The Science of Linguistics in the Art of Translation: Some Tools from Linguistics for the Analysis and Practice of Translation. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-887-06653-5; OCLC 15856738

- *Marcello Sorce Keller, "The Problem of Classification in Folksong Research: a Short History", Folklore, XCV(1984), no. 1, 100–104.

- Chester D Rowe and Stephen M Davis, 'The Excellence Engine Tool Kit'; ISBN 978-0-615-24850-9

- Härlin, M.; Sundberg, P. (1998). "Taxonomy and Philosophy of Names". Biology and Philosophy. 13 (2): 233–244. doi:10.1023/a:1006583910214. S2CID 82878147.

- Lamberts, K.; Shanks, D.R. (1997). Knowledge, Concepts, and Categories. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780863774911.

External links[edit]

Media related to Taxonomy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Taxonomy at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary- Taxonomy 101: The Basics and Getting Started with Taxonomies

- Parrochia, Daniel 2016. "Classification". In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy eds. James Fieser and Bradley Dowden.